It was only about a year and a half ago that NIWA staff came back from a research voyage to the Kermadec Trench led by their colleagues from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. With them they brought back many precious specimens and sediment samples from some of the deepest part of the trench, and they have been busy since processing and analysing the animals.

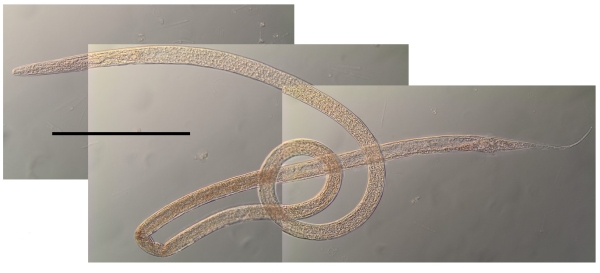

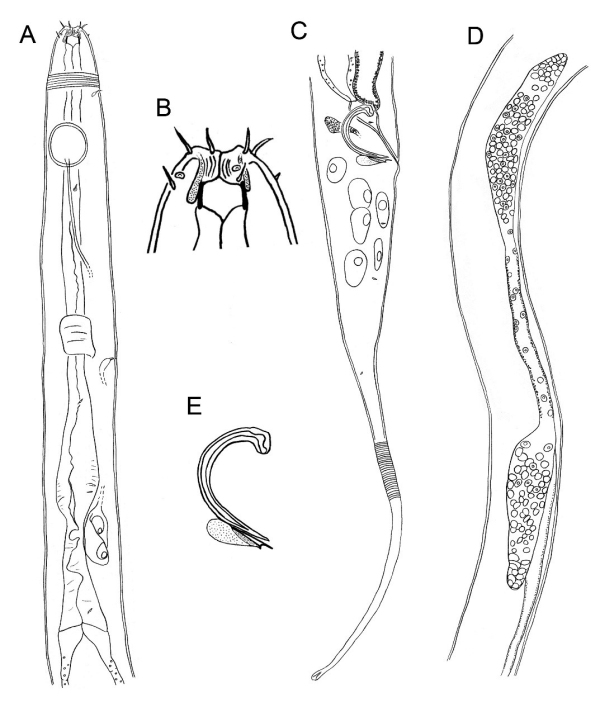

Many interesting discoveries were made, and among them was a new species of nematode worm called Thelonema clarki. This species was named after Malcolm R. Clark, a NIWA scientist who has made an outstanding contribution to the field of deep-sea ecology over the last few decades. Malcolm is one of the principal investigators of the HADES project (HADal Ecosystem Studies, funded by the National Science Foundation), which aims to better understand trench environments and how life has evolved to survive in these extreme habitats.

Deepest recorded nematode species

Thelonema clarki belongs to a genus only ever recorded once before, thousands of kilometres away off the coast of Chile. The new species, obtained at depths of 8000 and 9000 metres in the Kermadec Trench, is one of the deepest recorded nematode species and occurs much deeper than the only other species of the genus, Thelonema majum, which was recorded at a depth of 4000 m.

Thelonema clarki is pretty big for a nematode –it measures just over 4 millimetres in length! That’s more than twice the length of most nematodes in deep-sea environments, which seldom exceed 2 millimetres. Despite its “large” size, Thelonema clarki is thought to feed on very small food particles such as bacteria and detritus; this is because it possesses a small mouth without teeth. This is probably a good strategy since food resources in the deep sea can sometimes be very scarce, but bacteria are found just about everywhere.

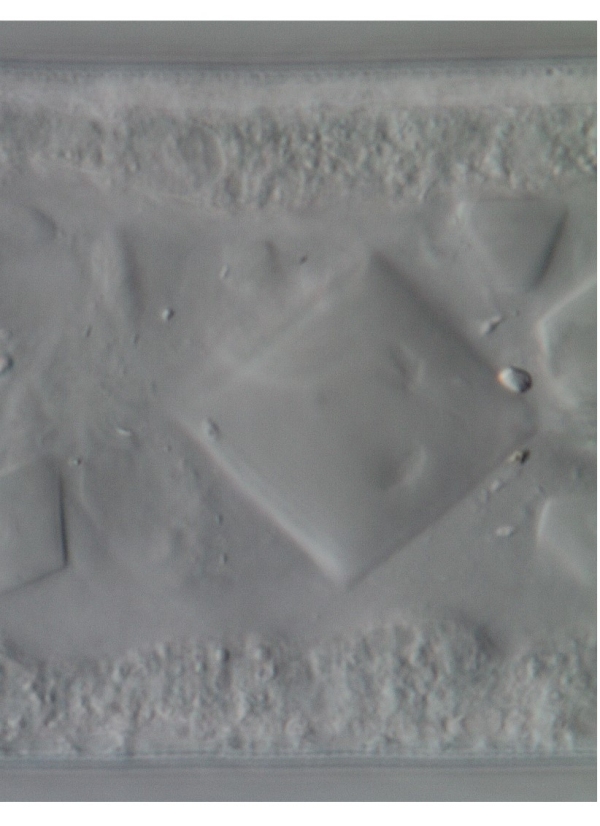

Mysterious feature

A strange feature of the new species is the presence of rather large crystalline structures in the intestine. These structures are too large to have passed through the small mouth opening, so probably grew inside the intestine itself. What these structures are made of, and why they apparently grow inside the intestine of Thelonema clarki, remains a mystery.