Deep dive into lakes

New Zealand has more than 3,800 lakes, with over 750 that are at least 500m long. Lakes are vital to life. Lakes are more than just places where all the water in an area collects: they provide fresh drinking water and irrigation supplies, water purification and regulation, habitats for fish and aquatic life, and storage to generate hydro-electric power. Lakes are also important for tourism, offer recreation and leisure opportunities, have cultural significance, and provide a sense of belonging.

Overlooked?

Despite their vital role in the cycle of water on our planet, and their ecological, economic and cultural importance, lakes are often overlooked. When examining the implications of a changing climate, despite their national significance, deep lakes remain under-represented in climate impact assessments.

A most excellent idea - the best lake to study

A recently completed research programme undertaken by Earth Sciences New Zealand (formerly NIWA) looked at the likely impact of climate change on lakes, in particular, deep lakes. Funded under the MBIE Smart Ideas, which supports promising, innovative research with high potential to benefit New Zealand, the three-year programme selected New Zealand's largest - and possibly - most iconic lake, Lake Taupō.

Largest, not just in New Zealand

With a surface area of 616 square kilometres, Lake Taupō is the largest freshwater lake in Australasia. Its maximum depth is approximately 184 metres - nearly the length of two rugby fields. Formed within a massive volcanic caldera created by the Ōruanui eruption around 25,500 years ago, the lake holds over 60 cubic kilometres of water. More than 30 rivers and streams flow into the lake, but it has only one outlet: the Waikato River — New Zealand’s longest river.

Quantity and qualities

Sitting in the middle of the North Island, Lake Taupō is highly valued for its crystal-blue waters, excellent water quality, stunning vistas, and its brown and rainbow trout. These important factors make Lake Taupō the ideal lake to study, as it supports biodiversity, hydro-electric generation, freshwater supply, and recreation and cultural values.

The challenge - deep lake vulnerability

Deep lakes are especially sensitive to long-term climate change because of their complexity, size, depth, and slow mixing cycles. Their volume makes them slow to respond, but their impact may be more significant. While in the Europe and North America scientists have some understanding of how the variables play out, in the Southern Hemisphere, not so much is understood about the interplay of factors.

So what are some of the factors that shape this dynamic environment?

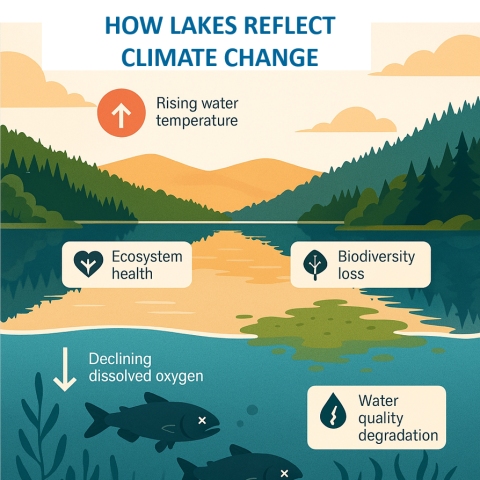

These include rising air temperatures, shifts in wind patterns, and changing inflows from surrounding catchments. These changes affect how lakes mix, how much oxygen is available at depth, and the overall health of aquatic habitats.

Smart ideas to understand complexity of lake health

The research has been addressing this knowledge gap by integrating the latest global climate projections for New Zealand (downscaled CMIP6), catchment hydrology, and a 3D lake model to simulate water movement, thermal dynamics, and dissolved oxygen levels. It also explores ecosystem behaviour using mathematical models and simulations. By integrating multiple models and the interaction of different components, known as coupled modelling frameworks, the researchers can simulate how the lake works as a whole and better understand its responses to climate and catchment influences.

Using this coupled modelling framework, scientists have been simulating how future changes in temperature, inflows, and wind will affect the lake’s thermal structure, deep mixing, oxygen availability, and habitat complexity – all key components of lake health and resilience. This study focuses on lake’s response on broader global climate influences rather than local developments in the catchment.

Key findings

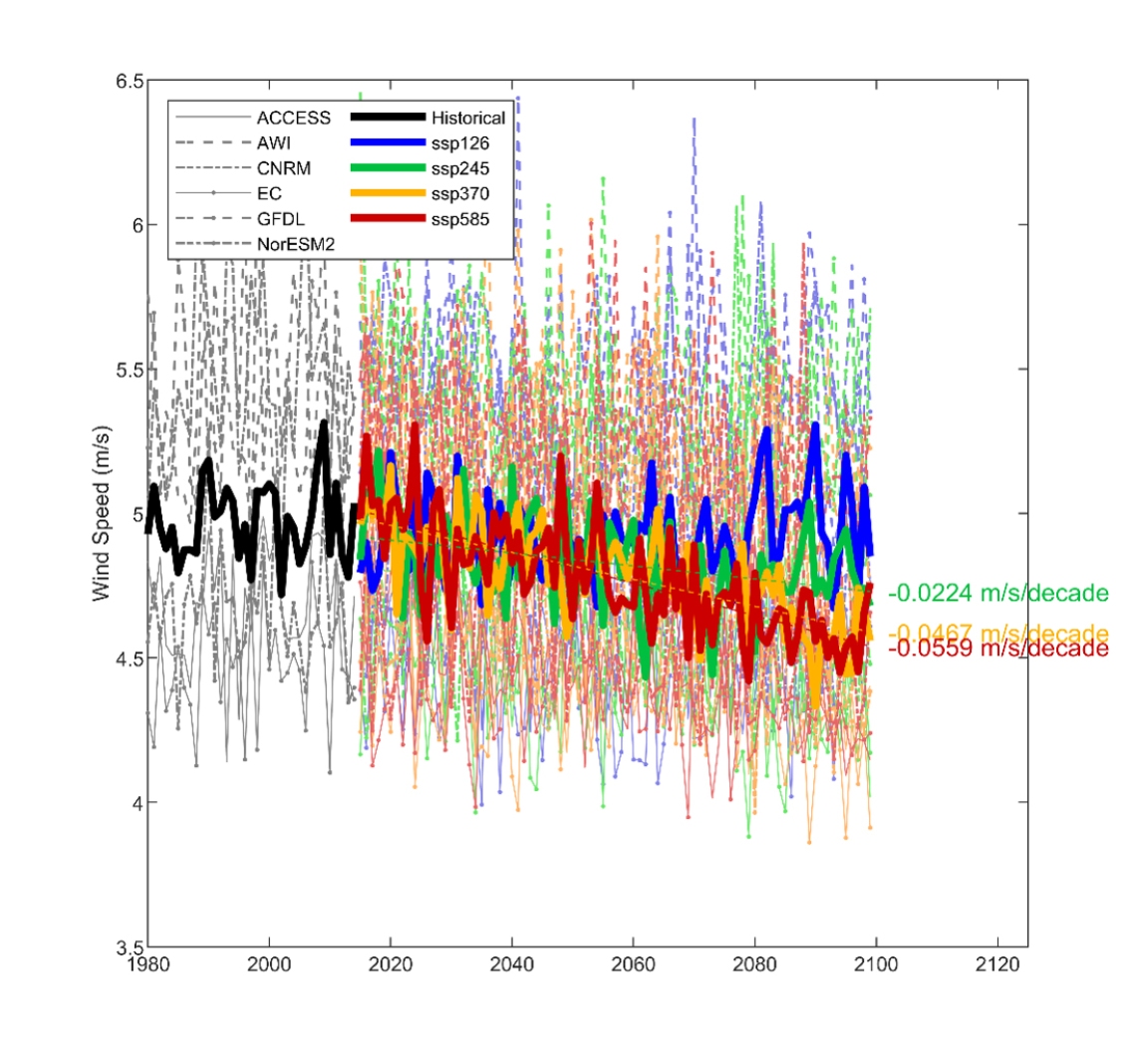

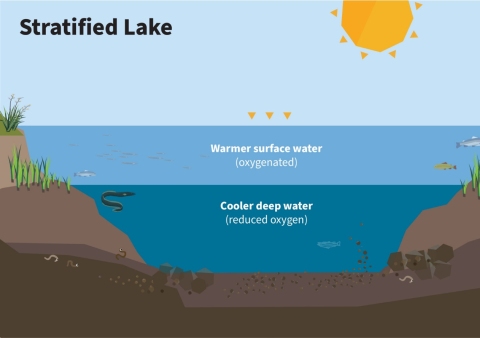

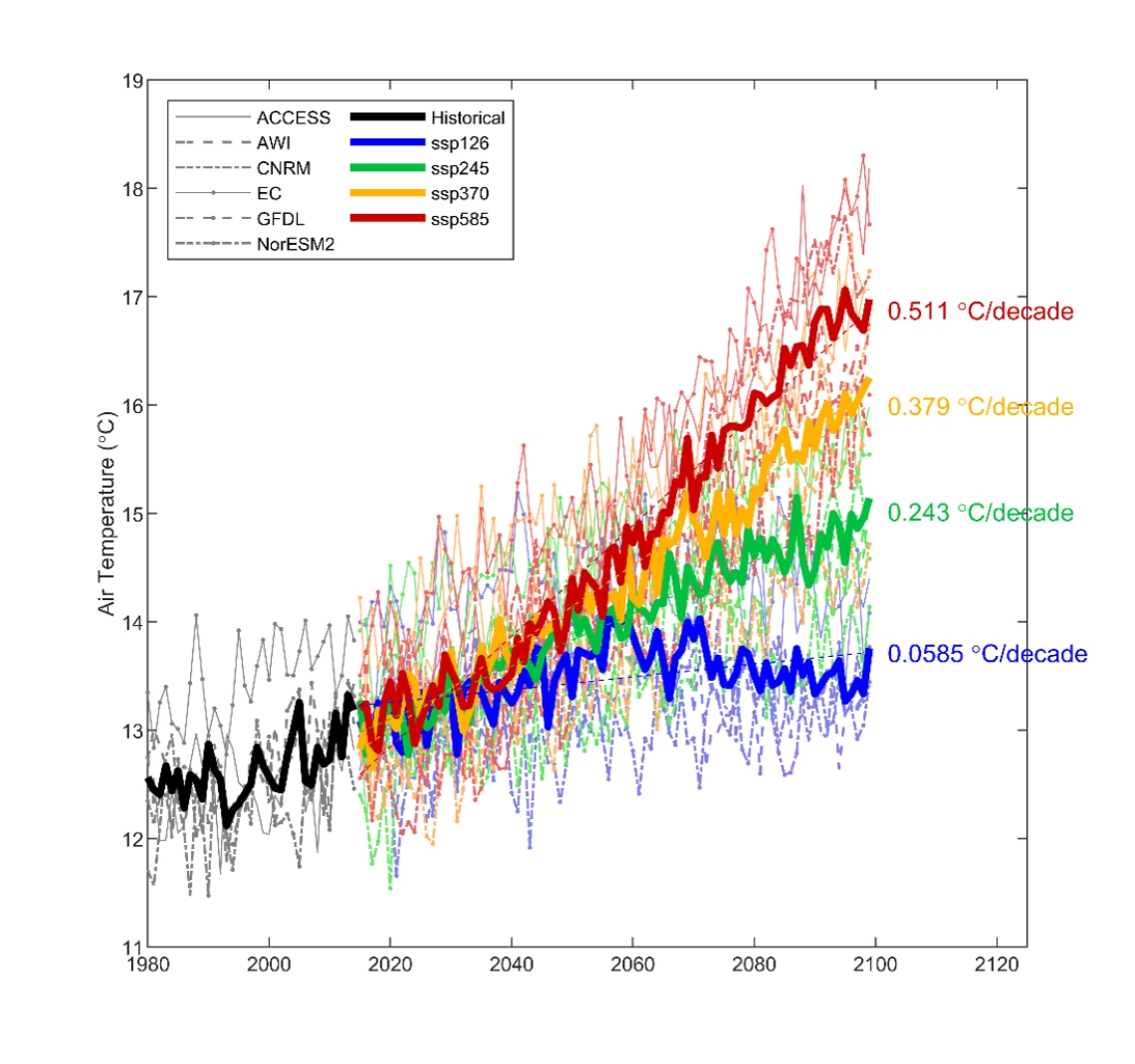

Our modelling shows that atmospheric variations are the main drivers of changes in lake temperature and oxygen, while river inflows play only a minor role. Air temperatures are projected to rise by 0.06–0.51°C per decade, and winds are expected to weaken. Because wind helps stir the lake and bring oxygen down into deeper waters, weaker winds mean less mixing and re-oxygenation. Together, these changes will make the lake warmer, with stronger summer layering that further limits oxygen renewal in deep water.

It is important to note that this study focused on the effects of climate change on lake temperature. Oxygen was simulated using a fixed rate of consumption, meaning that biological and water quality processes were not modelled as changing in the future. Within this framework, the simulations show that the lake will continue to mix each winter, even towards the end of the century, and oxygen levels are expected to remain within healthy ranges. A complete loss of oxygen in deep water is therefore not predicted.

These results highlight that future lake and catchment management decisions will need to consider the additional influence of rising temperatures, alongside other drivers.

Looking across several global climate scenarios, the modelling suggests:

- Summer surface waters will become warmer

- Wind speeds may drop, especially in winter, reducing lake mixing

- Stronger summer layering will restrict oxygen renewal at depth

- Less dissolved oxygen in the water column

- Reduced inflows from rivers could affect hydroelectric generation that relies on lake outflows

Wider impacts

These changes could affect:

- Aquatic ecosystems that are sensitive to temperature and oxygen

- The release of nutrients from lake sediments, which is influenced by temperature

- Overall freshwater quality

In-depth findings – temperatures and winds

Modelling using the 24 climate scenarios found that surface air temperatures over the lake are projected to increase. Under the latest IPCC future scenarios up to 2100, called Shared Socio-economic Pathways (SSPs), lake surface air temperatures could increase by a rate of 0.06 degree per decade under the coolest scenario, while under the warmest SSP, this could be 0.51 degree per decade.

As well as the surface temperature warming, the research identified two changes that together drive substantial shifts in lake behaviour, with a trend of decreasing wind speeds during summer and the lake’s seasonal mixing periods. The summer stratification season is projected to be stronger, reducing the depth of full-lake overturn, limiting the natural replenishment of oxygen in bottom waters, and increasing the risk of deep-water hypoxia.

In-depth findings - turbulence, mixing and waves

The model also captures changes in wind speed and patterns, which influence surface turbulence and whole-lake mixing. While weaker winds mean less overall mixing of the water column, under warmer scenarios large-scale internal waves — waves that move within the lake’s interior layers rather than on the surface — are projected to propagate more rapidly. Their speed depends on the temperature difference between surface and bottom waters. These internal waves can move nutrients and contaminants around the lake more quickly and enhance mixing near the boundaries, but they also carry risks such as increased turbidity, algal blooms, or disruption of habitats. In strongly stratified lakes like Taupō, the risks to water quality may outweigh the benefits.

What changes in oxygen, temperature and nutrient changes could mean for the fish

Our modelling suggests that aquatic habitats, including those important for trout, could change under warmer scenarios, particularly during late summer when conditions are most sensitive. To understand the implications for fish and other species more fully, these physical climate models can be coupled with dedicated habitat and ecosystem models. While nutrients were not directly modelled, the physical changes observed provide useful insights that can guide future studies on potential links to water quality and lake ecology.

Inputs and outputs

To support the modelling, we assembled an extensive historical dataset combining in-lake measurements of temperature, dissolved oxygen, and inflow data. Long-term observations from the Taupō mid-lake buoy and inflowing rivers enabled robust model validation and scenario testing. The findings underline how important it is to protect the health of Lake Taupō and to deepen our understanding of how it may respond to climate change.

Significance for deep lakes

This work provides important new insights into how deep lakes respond to climate change, with Lake Taupō serving as a globally relevant example. By capturing the combined effects of warming, altered inflows, and shifting wind patterns, the research highlights key risks to thermal structure, oxygen availability, and aquatic species habitat—issues that are likely to affect other deep lakes in New Zealand and beyond.

What’s the impact?

These findings are directly relevant for the protection of biodiversity, the resilience of biosecurity measures, and the long-term sustainability of hydroelectric generation that relies on lake outflows. The modelling framework and results can support freshwater managers, researchers, and policymakers in developing more informed strategies to protect lake health under future climate conditions.