Dr Emily Lane was out of phone reception on Saturday 15 January, when Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai erupted.

The Tongan underwater volcano created huge pressure waves, pumping enough energy into the ocean to unleash a 15-metre tsunami towards Tonga and send damaging waves out across the Pacific.

As ash from the eruption turned Tonga’s skies dark, Lane was one of many NIWA researchers who swung into action: from tsunami experts, to meteorologists, atmospheric scientists and marine geologists, it was all hands on deck.

Lane is a Christchurch-based tsunami modeller, who also studies underwater volcanoes. She returned to a flurry of messages, including an urgent request from New Zealand’s Tsunami Experts Panel. Lane is a member of the group, which is responsible for advising the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) about tsunami hazards.

An hour after their first meeting, the group urgently reconvened. One of New Zealand’s network of deep ocean tsunami sensors had just detected a large wave travelling away from Tonga.

“We hadn’t expected this, because volcanic tsunamis are usually fairly localised – to within a few hundred kilometres of an eruption,” says Lane.

The sensors were DART buoys and there are 12 of them in an early warning network set up three years ago by NEMA, NIWA and GNS Science. It extends up into the Pacific, along the Kermadec Trench and past Tonga.

“Having the DART buoys was a complete godsend – we would have been flying blind without them.”

Information from the buoys, alongside data from tide gauges in New Zealand and around the world, enabled the panel to estimate the scale of the impending tsunami and alert neighbouring Pacific nations.

Lane’s NIWA colleagues, hazard analyst Dr Shaun Williams and hydrodynamics scientist Dr Cyprien Bosserelle were meanwhile working directly with authorities in Tonga.

The previous day they had registered a smaller eruption and tsunami, foreshadowing Saturday’s event. Bosserelle says NIWA’s relationship with the Tonga Meteorological Service helped in the issuing of an early tsunami warning that probably saved many lives 24 hours later.

Despite the destructive waves and volcanic ash of January 15, all but one of the weather and sea-level monitoring stations NIWA has helped establish in Tonga remained operational.

Weather and wave data continued transmitting to New Zealand, and instrument technician Evgeny Fardman relayed this crucial information back to Tonga via one of the few live satellite links still operational.

This Tonga Meteorological Services data provided valuable insights into atmospheric pressure, weather and wave activity for researchers and emergency responders across the globe.

Auckland-based NIWA meteorologist Ben Noll says his first inkling of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai eruption came when he heard a strange rumbling sound at about 7pm.

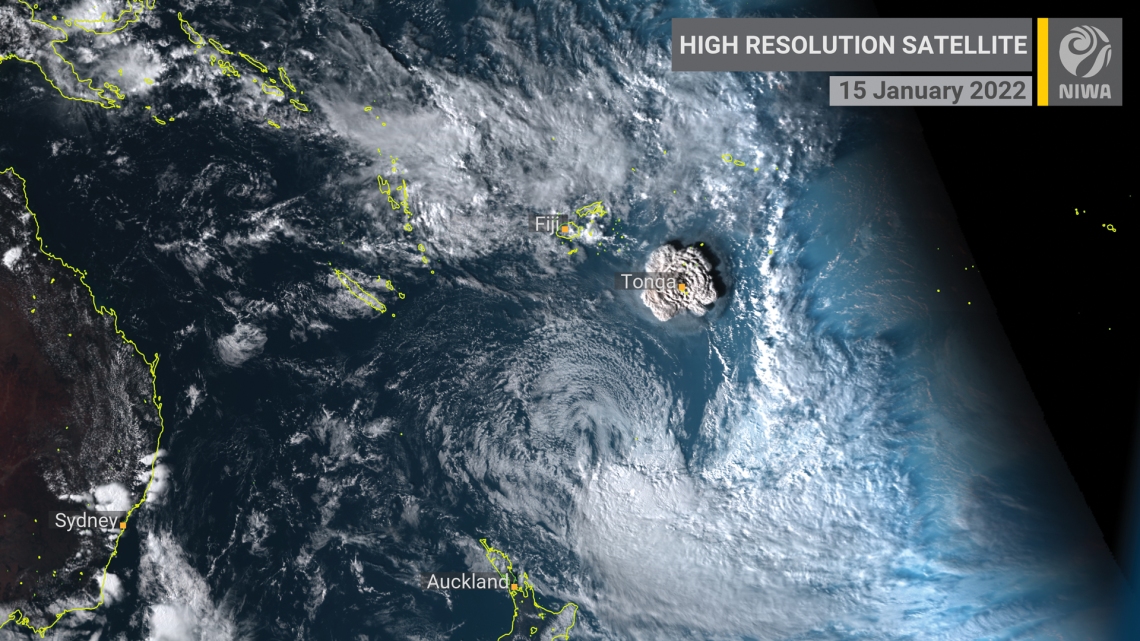

“I then saw the news and went straight to look at the images on Himawari, the Japanese weather satellite NIWA uses – it was the craziest thing I’ve ever seen on satellite imagery in all my years as a meteorologist. Just jaw-dropping.”

Noll posted the images online showing the enormous ash plume erupting into the atmosphere. These went viral, giving millions their first insight into the scale of the event.

In the days that followed, Noll worked with air quality scientist Dr Guy Coulson to estimate how much sulphur dioxide had spewed into the atmosphere. He then used weather data to create acid rain projections, helping Samoa and Kiribati assess the risk to drinking water supplies.

NIWA’s Lauder Atmospheric Research Station in Central Otago also tracked the ash plume and the atmospheric pressure wave, which circled the globe up to five times.

“We’ve kept the LiDAR running and are seeing the ash disperse slowly – a bit like the smoke from the Aussie bushfires in early 2020,” NIWA atmospheric scientist Ben Liley says.

Dr Richard Wysoczanski is a marine geologist at NIWA, as well as a volcanologist. He’s also a member of New Zealand’s Volcanic Advisory Panel. This group has played a key role in analysing the eruption and the lessons for the future.

“The eruption had about 1,500 times the explosivity of Hiroshima – it was on a scale that we didn’t think could happen,” he says.

Wysoczanski has analysed ash samples to work out the threat from trace metals leaching into the sea and poisoning fish.

He’s also helped plan RV Tangaroa's voyage to the eruption site. The multi-disciplinary expedition used multibeam echosounders to map the seafloor and provides a unique opportunity to investigate the explosion and its impact on the marine environment.

For Lane, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai was the “perfect storm”, bringing together all the different strands of her research.

“Scientifically, the eruption is the biggest thing that has happened during my career.”

She is now one of many scientists at NIWA, and across the globe, who is eagerly awaiting the results of Tangaroa’s latest research mission.

This story forms part of Water and Atmosphere - May 2022, read more stories from this series.