We examine how the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge plans to enhance the use of marine resources within biological constraints.

A report from the Ministry for the Environment in October 2016 found that most of New Zealand’s native marine birds and many mammals were threatened with, or at risk of, extinction.

A report by Statistics New Zealand in the same month showed the marine economy contributed 1.9 per cent, or $4 billion, to the nation’s GDP.

Vicky Robertson, Secretary for the Environment, points to human activity as a primary reason that marine habitats are in a fragile state.

“Fishing bycatch, introduced predators, and habitat change are among a raft of reasons for the poor state of much marine wildlife.”

In this context, the mission of the Sustainable Seas Challenge is not only apposite, but urgent. The Challenge contract was set by the Government over a year ago, and secured by a consortium of science organisations led by NIWA.

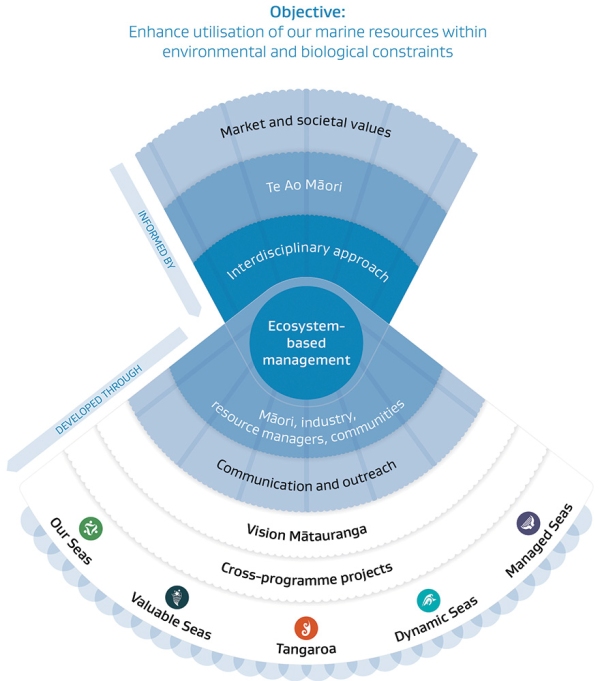

Challenge Director Dr Julie Hall is charged with bringing science and society together to develop better tools for managing our marine resources, to allow for many uses without losing ecosystem functions and benefits. She says the initial work of the Challenge identified that the best way to meet the objective is to pursue what is known as ecosystem-based management (EBM).

“Ecosystem-based management tries to account for and balance all the factors operating in an ecosystem,” Dr Hall says.

“Being armed with knowledge of how an ecosystem functions and responds to change, and what that system does for us, means that people can make better-informed decisions about what we do and the effect human activities will have on it.”

Dr Hall says the focus on EBM reflects the international consensus of science and policy makers.

“There’s a congruence of thought in policy and science circles that our use of environments must account for the multiple stressors affecting an ecosystem. That’s what policy wants, and it is exactly what science is looking at.

Dr Hall says that nailing the system will be an international first.

“There’s plenty of people looking at this around the world, but no one has put a fully integrated system into practice yet. So if we crack EBM, there’ll be a lot of international interest.”

Five streams

The Challenge has five streams of work, which knit together to provide data and knowledge to develop EBM.

Dynamic Seas includes all the projects investigating how marine ecosystems work, and Managed Seas is developing participation tools to make use of ecosystem models to manage the ecosystems themselves.

The “people” side of the project is reflected in the other programmes. Our Seas and Tangaroa research examines how people are involved with, and value, the sea.

Valuable Seas is building a framework to manage the economic, cultural and social values of the sea to New Zealanders. This includes identifying the range of services the marine environment provides to people, and the economic and non-monetary values of these.

The result will be knowledge of the intricate operation of ecosystems, so people can understand the impact of their use; a framework for managing the different forms of value people place on the sea; and a framework for bringing people together to make decisions about using the ecosystem.

“The Challenge will provide New Zealanders with the tools, framework, information and data to enable EBM to happen,” Dr Hall says.

Case in point

The Challenge has chosen an area across the middle of New Zealand to focus the first efforts at setting up ecosystem models.

Phase One will focus on the marine ecosystem in the Tasman-Golden Bay area by 2019. Phase Two will model two other areas, not yet chosen, by 2024.

Vidette McGregor, an ecosystem modeller at NIWA, is tasked with the job of running the “end to end” model for the Tasman-Golden Bay area. Her Greta Point office has the hallmarks of statistics-heavy work. A whiteboard is cluttered with calculations. Multiple side-by-side computer screens display screeds of spreadsheet data.

Ms McGregor’s computers use algorithms that represent the life cycles and predator-prey interactions of fish and shellfish species in Golden Bay, and contain data on factors such as ocean currents, nutrient levels, suspended sediments, and sunlight. They are built into the internationally-proven Atlantis template originated by Beth Fulton at Australia’s CSIRO.

Ms McGregor is testing the model, trying to perfect how accurately it represents what we already know the well-researched Bay looks like under the waves.

The simulation can represent half a million separate interactions of all the monitored factors. It takes a day to run a simulation that tracks 50 species, across 10 age cohorts, seeing how they evolve at 12-hour intervals over 100 years. The model was used to show what had happened to cause the disappearance of scallops from the Tasman and Golden Bay area over the past decade. Simulations accurately predicted the population decline due to increasing levels of suspended sediments from land use run off.

“When the model produces the same results we see in the wild, it can be used to explore scenarios. For example, what happens across the ecosystem if we increase the quota on a species? What happens to the ecosystem if sediment run off from land use is reduced?”

The model has had some early exposure to the public. It was introduced to a small local community to pilot the extent to which people could understand and use the initial model. Ms McGregor says that even with advances in computing power, the sheer volume of interactions makes it impossible to generate quick simulations of various scenarios.

“For now, we’ll simulate options in advance for communities to consider. We’re quite some way from trying out ideas and seeing what happens while you wait.”

Good services

The marine environment does a lot more for us than many people realise. These “services” include obvious ones like food, less obvious ones like oxygen and climate, and also less tangible things such as our cultural relationship with the coast.

Dr Judi Hewitt, a NIWA Principal Scientist in Marine Ecology, is leading Valuable Seas, which will quantify the services provided by marine ecosystems.

“Marine ecosystems underlie our values and the quality of our lives. A good EBM system will not only weigh the relative values of what we need from the ecosystem, it will take into account the relative cost to people of losing or gaining things that are important to them about the ecosystem. We’ll start by counting the services and calculating their value to people, economically, socially and environmentally."

Dr Hewitt says the work is “thorny”.

“People value our seas differently. We need to discuss these differences to understand the personal value systems people have. This analysis will help us to establish the core and common values.”

She says one way the project is testing the values is to examine a handful of specific services and activities that people conduct with the sea. The research will look at whether, and how, ecosystem degradation has changed the perceived value of the services. Dr Hewitt’s colleague, Dr Drew Lohrer, is running workshops with New Zealanders to look at all the possible services, and evaluate their worth. Jim Sinner, a senior scientist in Policy and Planning at the Cawthron Institute, is running the project merging scientific, social and economic values.

The Blue Economy workstream is just as thorny. Dr Hewitt says that while the economic outputs are well understood, the relative values between economic users of the sea is less clear.

“For example, quotas are obviously an economic limit on fishing, but they also affect others who provide services to fishing, or make money off side-effects of the practice. At the same time, quotas could provide economic opportunities for new innovative ways of making use of that species,” she says.

Valuable Seas is tasked with finding those opportunities within sustainable limits. The Challenge has an innovation fund of $1.5 million per year for research projects that identify methods that increase diversification and add value to the marine economy. It is currently examining proposals.

Evolution of a species

Dr Hall says the project is the start of a long-term transition to using EBM to manage human interaction with the marine environment. She points to cross-programme projects that will help disseminate and integrate knowledge into current practice.

“The Government is determined that none of the science output is left on a shelf—it must be made use of. We’re looking at how EBM can be worked into policy, how legislation can be modified to reflect EBM principles and practice, and we’ll be trialling EBM in the field.”

She says there are many routes for the Challenge’s findings to integrate with current practice.

“For example, the fisheries legislation is under review right now. It’s at these sorts of times that policymakers will have opportunities to incorporate EBM principles.”

Dr Hall says there is no single output from the Challenge, and no moment of truth when the EBM system kicks in.

“We won’t switch suddenly from the current practices into EBM—it will be an evolution. Lessons learned from Sustainable Seas will be gradually built into existing systems. Over time, we will step closer and closer to management based on understanding of the marine ecosystem, and on full community discussion about what we need and value.

“In 10 to 15 years’ time EBM could cover the whole of New Zealand.”