NIWA scientists have found signs of recovery in the Kaikōura Canyon seabed, 10 months after powerful submarine landslides triggered by the November earthquake wiped out organisms living in and on the seabed.

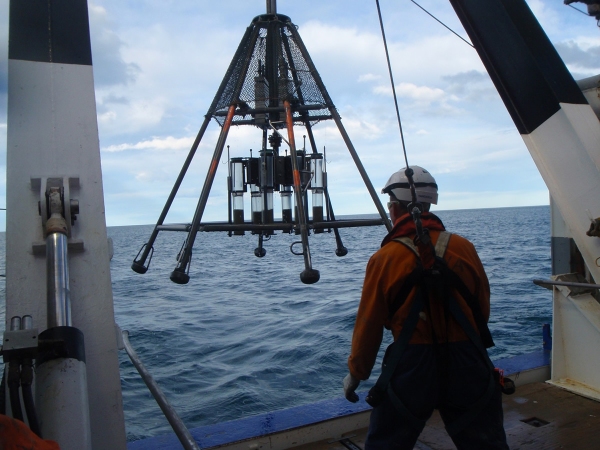

A team of scientists aboard NIWA’s research vessel Tangaroa, have just returned from surveying the effects of the earthquake on the deep sea ecosystem in the Kaikōura Canyon.

The November 2016 earthquake caused submarine mudslides and sediment flows that had devastating effects for the abundant deep-sea life in the canyon. Before the earthquake, the canyon was recognised as one of the most productive deep-sea ecosystems on Earth, which is partly why the upper canyon is now protected by the Hikurangi Marine Reserve.

In the months following the earthquake, NIWA remapped parts of the seafloor and obtained samples and video footage from the region. These showed the extent of the disturbance caused by the earthquake, and the catastrophic impact on animal communities that live in the canyon.

In July this year, NIWA surveyed the seafloor of the entire Kaikōura Canyon area using a multibeam echosounder seafloor-mapping system on RV Tangaroa, which revealed modifications made to the seafloor by submarine landslides triggered by the earthquake.

The most recent voyage, completed on Sunday, was specifically designed to sample the seafloor that had been scoured or buried as a result of the submarine landslides, and begin to determine the potential recovery of the deep-sea ecosystem.

Recovering faster than originally thought

NIWA ecologist Dr Daniel Leduc said there was evidence that juveniles of animals that once dominated the head of the canyon have now begun colonising the seafloor.

“The deep-sea communities might be recovering faster than we originally thought, with high densities of small organisms such as urchins and sea cucumbers in some areas of the canyon, as well as large numbers of rattail fishes swimming immediately above the seabed.”

Voyage leader, geologist Dr Alan Orpin, said that in the upper canyon there was evidence of eroded old muddy seafloor with fresh deposits of soupy mud on top.

“In the lower canyon we sampled gravel waves, comprising well-rounded greywacke pebbles. We think that these waves were reshaped by powerful sediment-laden flows triggered by the earthquake.”

The multidisciplinary NIWA team also included scientists studying the structural and chemical changes in the canyon sediments, as well as biologists looking for signs of recovery in the animal communities by taking core samples and video of the seafloor.

Biogeochemist Dr Scott Nodder said there was “a widespread fluffy muddy layer on the seafloor surface characteristic of the upper canyon. This is different from samples collected from the shallower Conway Trough that branches south off the main canyon. There, our first impressions suggest less impact of the earthquake on the seabed environment”.

Among the participants in the voyage were students from the universities of Waikato, Auckland and Otago, and a whale observer from Whale Watch Kaikōura.

Dr Ashley Rowden, the overall leader of NIWA’s Kaikōura Earthquake deep-sea project, said that he was pleased to hear about the results from the voyage, and excited about what they will reveal about the effects of large earthquakes on deep-sea ecosystems.

“Following the earthquake, the people of Kaikōura have had to deal with a lot of disruption, economic troubles and other issues. So, it is good to find indications that the deep parts of the canyon - which contribute to maintaining a healthy functioning ecosystem on which some of the community rely - is beginning to recover.”