PDF of this article (140 KB)

Jody Richardson Jacques Boubée

Stream restoration is actively promoted by many regional and local authorities. But does it work? We assessed a restoration project eight years on and conclude yes, but...

Many people agree that human activities can harm stream environments, and many are interested in doing something about it. Today, most regional and local authorities actively promote stream enhancement by providing appropriate information in their publications or by funding local community groups to undertake restoration projects. They can also set rules designed to reduce or avoid impacts as conditions of resource consents.

Genesis Power Ltd holds resource consents to discharge cooling water from Huntly Power Station into the Waikato River. One of the conditions of these consents was that a programme of enhancing and maintaining fish habitats be initiated in at least two tributary streams of the Waikato River. In this article, we review the project and draw conclusions about stream restoration.

Native forest restoration

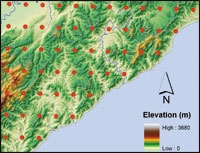

In 1995/96, Genesis selected three tributaries of the Waikato River draining the Hakarimata Range between Huntly and Ngaruawahia for restoration. The headwaters of all three streams are in native forest but, prior to restoration, livestock could access the waterways and vegetation. The lower reaches ran through pasture, where livestock also had access to the streams (see “before” photograph).

One objective was to establish a native forest corridor along the streams to connect the canopy in the Hakarimata Scenic Reserve with the Waikato River and to encourage indigenous fish to become resident in these streams. After consultation with the landowners, Genesis installed 12 km of fences and 12 stock-water troughs, built 5 bridges, and planted over 10,000 trees and shrubs along the riparian margins (see “after” photograph). Streams were also checked to ensure that there was unhindered fish passage.

NIWA conducted pre-restoration fisheries surveys on two of the streams in 1995. The consents required that monitoring be carried out until:

- The abundance of indigenous fish has increased by 50% or more, or

- one additional significant indigenous species has established as a viable population.

Mixed results

In 2003, identical fish surveys were carried out to measure whether the objectives had been achieved. Results for the two streams surveyed in both 1995 and 2003 differed (see graph). In Stream A, most species increased in number, as did total fish numbers, although the increase was less than 50% (from 63 to 80 fish per 150 m of stream). Although the abundance of banded kokopu in Stream A decreased a little over the whole stream, more banded kokopu were found in the restored reaches than previously, suggesting they were becoming established in the restored habitat. A new species, lamprey, was found in Stream A, but common bully disappeared.

In Stream B, the abundance of banded kokopu and redfin bully increased at least 50%, eel abundance reduced 50%, and giant kokopu numbers stayed about the same. As in Stream A, common bully were not found in Stream B in 2003. Overall, fish abundance in Stream B decreased from 71 to 63 fish per 150 m of stream between 1995 and 2003.

Success or not?

Do the results so far mean the restoration project isn’t working?

Not at all. The results simply reflect the expected change in fish community as the habitat evolves from a pastoral to forested stream. The abundance of species that prefer forested streams (banded and giant kokopu, redfin bully) did increase, and often by at least 50%. In contrast, abundance of the pastoral species (common bully and eels) reduced, and because eels were the most abundant species in Stream B, this meant total fish abundance went down. If the wording of the objectives had accurately reflected what was really expected to happen, i.e., that the abundance of forest-dwelling indigenous fish should have increased by at least 50%, then the first monitoring objective would have been met.

For the presence of a new species, success is even harder to measure. The only new species found was juvenile lamprey in Stream A. Although these fish live in freshwater for about four years before migrating out to sea, it is difficult to ascertain whether this represents a “viable population”.

Time and maintenance needed

In our opinion, this project will be successful, particularly as the habitat matures. However, the findings highlight some important points about restoration activities.

First, it has taken several years for the riparian vegetation to grow and affect the stream habitat. It will probably take another 15 years or more before the lower reaches completely resemble forested streams. The adage that “good things take time” certainly applies to restoration projects.

Over the past eight years, the fences and other structures have required essential repairs. Livestock getting into one fenced-off section of stream can ruin years of plant growth and bank stabilisation in just a short time. The riparian vegetation has also needed maintenance, including replacement of dead plants, thinning, and weed control. In some places, the restoration has worked too well, and the streambed has become infested with flax, which is trapping silt and woody debris. In time, this will turn the stream into a wetland, which was not the intention. It is now necessary to remove some flax bushes, a job that could have been avoided if the flax had been planted farther from the stream banks.

All these activities take time and money, which in this case have been supplied by Genesis.

Set realistic goals

It is also critical that the objectives are carefully thought out at the start of the project. The first objective in this project was good because there was an actual measure of success (i.e., a 50% increase), but the wording didn’t reflect the biological requirements of the species and hence the real outcome of re-foresting these streams. In the second objective, words like “viable population” and “significant species” needed to be defined.

So, we definitely encourage stream restoration projects, because they do work. But, to be successful, restoration projects must have realistic goals and a group prepared to be involved for the long haul. To be rewarded with a restored stream, workers must be patient, stay involved and interested, and set clear, measurable goals.

Teachers: this article can be used for NCEA Achievement Standards in Agricultural/Horticultural Science (1.5, 1.7, 2.3), Biology (1.5, 2.3, 2.5, 3.2), Geography (1.3, 1.6, 3.1). See other curriculum connections at www.niwa.co.nz/pubs/wa/resources

Jody Richardson and Jacques Boubée are based at NIWA in Hamilton.

This work was jointly funded by FRST (contract C01X0210) and Genesis Power Ltd.