When we for the first time surveyed the Admiralty and Scott Island seamounts to the north of the Ross Sea in 2008, we encountered striking meadows of stalked crinoids at around 600 m depth on isolated knolls along the northern and southern flanks of the seamount (see photos).

Admiralty and Scott Island seamounts

Around the live sea lilies, masses of fragments of long-dead sea lilies indicate that these populations have persisted for a very long time. What fascinated the scientists was that the assemblages found on this seamount, the sea lilies and neighbouring meadows of filter-feeding brittle stars are more reminiscent of those found in the fossil records from around 55 million years ago (the late Eocene and early Paleocene). They think that this particular seamount, isolated in the frigid waters of the Southern Ocean for a VERY long time has maintained these ancient animal communities (1).

Ptilocrinus amezianeae

When specimens of this large crinoid (see Cotw 80 and 130 for our introductions to crinoids) were sent for examination by the experts at the Paris Museum, they concluded that this was a new species and named it in their recent paper in the journal Polar Biology.

Eléaume et al (2011) paper describing the crinoid species

The authors comment on the fact that we have not only provided them with a large sample size of specimens that range from small juveniles to large adults, which is very useful if you are describing species, this was also the first time that hyocrinid stalked crinoids were documented with photos and videos of them living in their natural habitat.

Interestingly, another specimen in their own collection matched their new species description, but this one was collected from the Kerguelen Plateau, on the other side of the Antarctic. Since then, many specimens from the slopes of the Kerguelen Plateau have been collected and another population has been discovered from the Scotia Arc. So, as far as we know this species appears to have a wide range with populations in these widely separated isolated seamounts.

The species is dedicated to Dr Nadia Améziane, another curator at the Paris Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle and Director of the Marine Biology station in Concarneau in Brittany, France. The authors note her extensive contributions to the understanding of the systematics of living crinoids.

You can read Chris Mah’s Echinoblog report on this species which includes a (blurry) photo of Dr Améziane here.

A lost world?

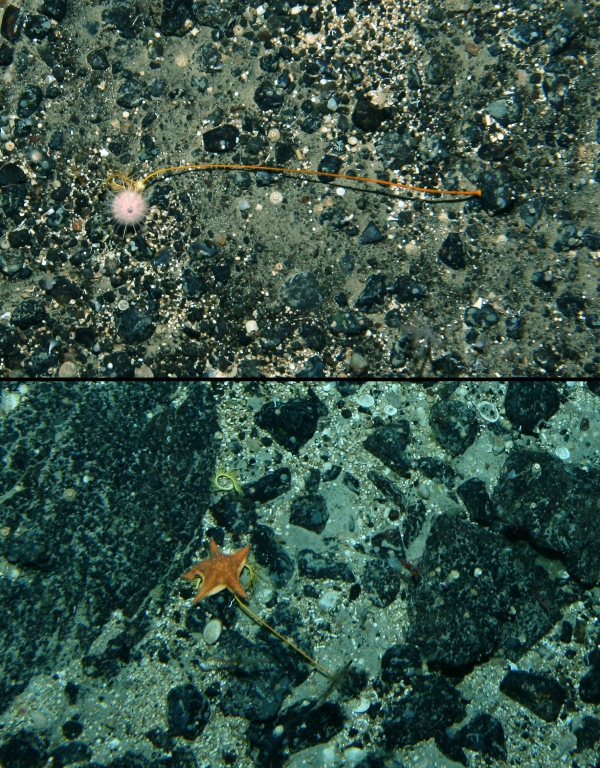

These aggregations of crinoids in such high numbers had to date not been observed for these stalked crinoids and they remind scientists of fossil finds dating back over 50 million years ago on the opposite side of the Antarctic continent. Aronson et al. (1997) report fossil assemblages of tens to hundreds of closely related stalked crinoids at the La Meseta formation on Seymour Island, East Antarctic Peninsula, which dates back to the late Eocene epoch. So why are these assemblages on Admiralty and the neighbouring Scott seamount and not elsewhere? It has been suggested that the once-plentiful crinoid assemblages in other parts of the world have been slowly declining due to the evolution of ‘modern’ mobile predators such as crabs or fish. Incidentally, these are very scarce on our seamounts due to their location in the Southern Ocean and distance from large land masses. That we observed these crinoids being preyed on (see photo) by a starfish and an urchin is taken as proof that they are susceptible to predation. But Bowden et al. (2011) can show that that the presence of these predators is much lower on our seamounts compared to other areas. The implication being that, if there were high numbers of these predators on Admiralty and Scott seamounts, we would probably not see these meadows of stalked crinoids. So do these communities represent a lost world?

So the authors ask whether we can find out how long these crinoid communities have persisted at that location (1). While they caution that very little is known about the growth rate, expectations would be that these rates would be extremely slow because of the nutrient-poor and cold waters around the seamount. And then they point at the squillions of ossicles (the small disks that crinoids are made of) that are littering the sea floor and crinoid bases still attached to the rocks, evidence of a crinoid that were formerly attached but has since died (see photo). Until this can be studied in detail, they suggest that it is likely that these meadows have persisted for centuries and possible millennia at this location.

Links of interest:

Chris Mah’s Echinblog featured the Lost World story back in 2011 and presents lots more photos and some more explanations here.

This story also made it into the New Scientist back in 2011, read it here.

Reference:

1) Bowden DA, Schiaparelli S, Clark MR, Rickard GJ (2011) A lost world? Archaic crinoid-dominated assemblages on an Antarctic seamount. Deep-Sea Research II 58: 119-127.