Tuna harvested from Lake Ōmāpere and Utakura River catchment have long comprised an important fishery for tangata whenua.

This case study describes a recent research project to investigate the tuna populations of Lake Ōmāpere and its only outlet, the Utakura River, to provide a reference point for future monitoring and research, and knowledge regarding the health of Lake Ōmāpere and its impact on the taonga species for which it was traditionally renowned.

Introduction

In 2007 Ngāpuhi Fisheries Limited were successful at securing funding from Te Wai Māori Trust to investigate the population structure of freshwater eels in Te Tai Tokerau [Northland] in order to provide a reference point for future monitoring and research. The first "tuna training workshop" programme was designed and delivered to tangata whenua who attended from all over Te Tai Tokerau. Workshop attendees discussed and refined where future efforts should be focused in terms of the field work component. During this inaugural workshop, Lake Ōmāpere was identified as the focus for a baseline tuna survey.

Lake Ōmāpere is of great cultural and environmental value to Māori. During the last seven years the Lake Trustees and a Project Management group have worked on a major restoration project to improve the water quality and the desired state of waiora.

The Lake Ōmāpere Project Management Group, which comprises hapū with manawhenua in the area, and a number of relevant agencies, prepared a Restoration and Management Strategy for Lake Ōmāpere in 2006. The strategy aims to improve the health of Lake Ōmāpere by strengthening kaitiakitanga. It outlines a series of practical actions and outcomes which are required to achieve the overarching vision of waiora.

Waiora describes the life-giving element of the Lake which can only be fully realised when it is restored to a healthy condition where the people and the wider environment can benefit. Four central elements were identified as important to achieving waiora:

- Ma uta ki tai: Emphasising the total connectedness of the natural environment and acknowledging that Lake Ōmāpere will not be restored through isolated initiatives or a narrow focus.

- Mātauranga: Has been broadly viewed as knowledge or teachings which underpin kaitiakitanga. The urgent need to focus on knowledge regarding Lake Ōmāpere and its context environmentally, historically and spiritually. This will enhance the cultural indicators that are appropriate when considering long term monitoring of the health of the lake and its environment.

- Rangatiratanga: Conveys the sense of authority, control and responsibility inherent in the exercising of kaitiakitanga. There is a need to ensure appropriate structures and practices are in place to support the long term restoration of Lake Ōmāpere.

- Kotahitanga: Refers to a unity of purpose in relation to Lake Ōmāpere and the importance of the development and maintenance of relationships to support such a purpose.

Methods

The fieldwork conducted to complete this survey was undertaken by members of the Lake Ōmāpere Trust, Te Roopū Taiao o Utakura and NIWA in November 2008.

A combination of sampling methods was used during the survey including:

- coarse mesh fyke nets

- fine mesh fyke nets

- electric fishing

- Gee-minnow traps

- a gill net.

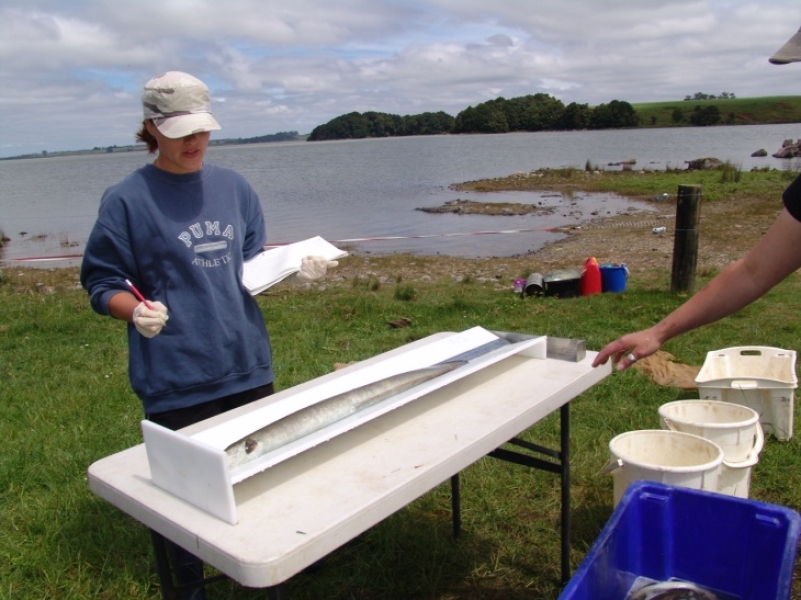

All of the tuna caught were anaesthetised, identified by species, measured and weighed. Where possible, the sex and stomach (diet) contents were identified for each tuna that was sacrificed for ageing purposes. The swim bladder was examined for the presence of parasites. By-catch information (species, numbers captured and fork length) was recorded. For ageing purposes ,otoliths were removed from a selection of the tuna captured.

Results

A total of 929 tuna (271 kg) were captured during the survey with 73% of this catch obtained from Lake Ōmāpere itself. Overall, longfin tuna comprised 9% of the total catch from Lake Ōmāpere and its south-western tributaries, and 17% of tuna from the Utakura River and associated tributaries. Although both shortfin and longfin tuna were captured at 83% of the sites sampled during this survey, overall the numbers of longfin tuna were low. While shortfins dominated the catch from Lake Ōmāpere, longfins were more common in tributaries of the Utakura River.

The age distribution of the eels captured during this study indicated that shortfins were between 3 and 13 years of age, while longfins were between 4 and 16 years. For both tuna species, the lowest average annual length increments were generally recorded below the falls in the Utakura River catchment. Observations indicate that shortfin tuna growth in Lake Ōmāpere is amongst the highest recorded in New Zealand to date.

The minimum length at which female longfins can mature and emigrate is about 75 cm. Of eels sampled during this study, only about 2% of the longfin eels captured during the survey exceeded this size. The time needed for longfin females to reach the minimum reproductive size in Lake Ōmāpere and the Utakura River catchment is estimated to take about 13 years.

This survey indicates that very few large females are supported by the catchment and thus contribute to the spawning stock. These results emphasise not only the vulnerability of the population to fishing pressure but also indicates that management measures taken nationwide could take decades to show results. In order to better understand the effect of harvest on the size and species composition of the eel population over time, robust information on harvest (commercial, recreational and customary) activities within the Lake Ōmāpere and Utakura River catchment is required. As a precautionary measure, to ensure future recruitment, it is recommended that fishing pressure (including customary and recreational take) on large female tuna be reduced, an action that may benefit future eel recruitment into New Zealand waters.

This research will assist the Lake Ōmāpere Project Management Group to achieve its vision of waiora, by providing baseline information required to monitor and adaptively manage the long term wellbeing of the Lake Ōmāpere and Utakura River tuna fishery.

On-going work

Te Roopū Taiao o Utakura have successfully secured funding from the Health Research Council of New Zealand (HRC) to undertake the research project "Working for the river will lift the health of the people". The objectives of this research include:

- Measure the water quality of the Utakura River and its tributaries;

- Measure the health and wellbeing of their people;

- Assess how the health of the river affects the health of the people;

- Test selected ideas about how to improve water quality.

A multi-disciplinary team has been assembled to collaborate and deliver this research including Te Roopū Taiao o Utakura (lead organisation), Te Roopū Whāriki (in partnership with Massey University's Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation), Northland Regional Council, Waikato University, Landcare and NIWA.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Te Wai Māori Trust and conducted by Ngāpuhi Fisheries Ltd (NFL), the Lake Ōmāpere Trust, Te Roopū Taiao o Utakura and NIWA.

References and further reading

Henwood, W., Henwood, R. (2011). Mana whenua kaitiakitanga in action: Restoring the mauri of Lake Ōmāpere. Alternative 7(3): 220-232.

Lake Ōmāpere Project Management Group (2006). Restoration & Management Strategy for Lake Ōmāpere. Prepared by the Lake Ōmāpere Trust and the Northland Regional Council. 44 p.

Williams, E., Boubée, J., Dalton, W., Henwood, R., Morgan, I., Smith, J., Davison, B. (2009). Tuna population survey of Lake Ōmāpere and the Utakura River. NIWA Client Report WLG2009-39. April 2009. 90 p. https://waimaori.maori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Ngapuhi-Fisheries-Limited-Final-Report-09.pdf

Other links: