29 January 2019. By Voyage Leader Dr Richard O'Driscoll.

Day 21 of the Ross Sea Environment and Ecosystem Voyage 2019 on RV Tangaroa. For the past week we have been on the Iselin Bank—a large submarine ridge that rises from over 2000 m deep up to about 500 m.

As I mentioned in my last update, Iselin Bank is one of the main fishing grounds for Antarctic toothfish. This year’s Ross Sea toothfish fishing season started on 1 December 2018 and finished in this area on 6 January, once the annual quota set by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was caught. The Ross Sea fishery is an international one: 24 vessels from 9 countries were licenced by CCAMLR to participate in 2018/19. The fleet included three fishing vessels from New Zealand.

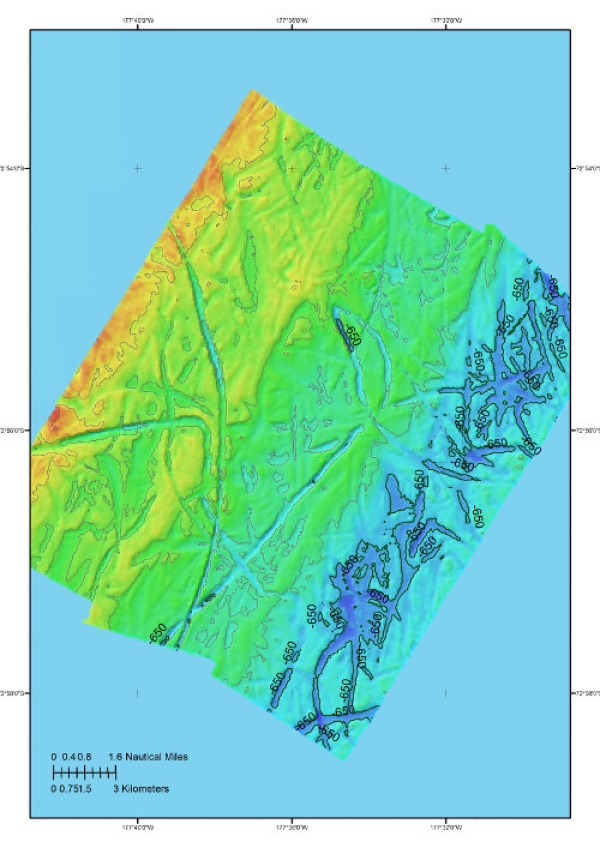

We are looking at the seabed habitat and abundance of bycatch fish species in the fished area, as well as further south and east in the regions closed to fishing by the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA). We have 30 randomly generated sites scattered across the continental slope between 600 and 1500 m depth. At each of these sites we start by mapping the seabed using a multibeam echosounder to get an accurate picture of the depth and terrain.

We then send down NIWA’s deep-towed imaging system (DTIS). We tow DTIS slowly about 2 m above the seabed for an hour taking still and video images of the bottom and the animals that live there. Finally—if the multibeam and DTIS suggest that the bottom is suitable (i.e., relatively flat and not covered in vulnerable marine animals like sponges or coral) - we carry out a short trawl to collect samples.

So far we have completed 15 of the 30 sites. Of these 3 were not suitable for trawling as they had large rocks, sponges, or deep grooves carved by icebergs. When you are in more than 600 m of water it is hard to comprehend the size of an iceberg that would be dragging on the sea floor!

We have already seen some neat things. At one site last Friday we noticed some unusual round patches of dark gravel in the seabed images. The five of us who were gathered round watching the live DTIS video feed wondered what these were? Once we downloaded the high resolution video and still images from the DTIS camera, Simonepietro Canese, our Italian fish scientist onboard, announced that these were icefish nests—as evidenced by the proximity of a single icefish near most of the dark circles. Sure enough, when we trawled nearby we caught some large mature specimens of the long-fingered icefish (Cryodraco antarcticus).

Icefish (Channichthyidae) are a unique family of Antarctic fishes. Their most notable feature is the absence of haemoglobin, which means their blood and gills are completely white! Several species of icefish have been observed building nests. In fact, Simonepietro’s Italian colleagues described this behaviour after observing captive specimens of a related species in an aquarium in Genoa. But because of the extreme Antarctic environment, this has seldom been observed in nature, and (as far as we are aware) never for this particular species. It is thought the female lays sticky eggs in the gravel nest where they are then guarded by the male.

Although feeling slightly guilty for raiding the nursery, it was extremely valuable to collect a few specimens in our trawl to confirm the species we were seeing. The icefish species look so similar that even out of the water they are difficult to tell apart. After scientific sampling, the icefish that we caught were filleted for the galley. They were delicious—like flounder—which also helped to ease the guilt!

Another important bycatch species of the toothfish fishery is the rattail (or grenadier if you are in the fish marketing business). Rattails are doubly important as they are also a favourite food for toothfish. Monitoring rattail abundance is a key objective of the Ross Sea Research and Monitoring Plan. There are two main rattail species in the Ross Sea. The results we are seeing suggest that these species have different, but overlapping, depth distributions. The shallower-living species (Macrourus caml —so named because it was described by NIWA scientists from specimens collected on the International Polar Year Census of Antarctic Marine Life (CAML) voyage on Tangaroa in 2008) also occur away from the seabed. We have made several catches of rattails more than 100 m above the bottom in midwater trawls, while targeting fish that we can ‘see’ on the scientific echosounders. This provides some hope that we might be able to use acoustics to estimate rattail abundance in the future. This has a couple of advantages for future monitoring: first, you don’t have to trawl; and second, New Zealand fishing vessels already routinely collect their echosounder data, so we might be able to monitor rattails using existing data.

As well as the fishy stuff, all the other routine sampling activities have continued. The microbial team I talked about last week are excited as they are seeing different phytoplankton composition in the shallow water on the top of Iselin Bank compared to in the deeper slope water. The zooplankton team have started deeper Bongo net sampling in lieu of the MOCNESS—which failed on its first deployment at Cape Adare and could not be resuscitated. And last but not least, we recovered the final mooring—a whale listening post—from the eastern Iselin Bank on Sunday. A replacement instrument was deployed yesterday in a new position to the west, which is deeper, and further away from the fishing grounds.

Very foggy, and often snowy, conditions have meant the whale sightings have been down, but we had fleeting visits from pods of killer whales (orca) on Sunday and today, which brightened the day of those who saw them. The sun finally broke through yesterday and we got to see blue sky for the first time since we left Cape Adare.

Over the next week we will continue to work south and east down the slope. We have just entered the Special Research Zone of the MPA.