An animal entirely made out of glass? We don’t have to go to an alien world for this. We just have to look deep into our oceans.

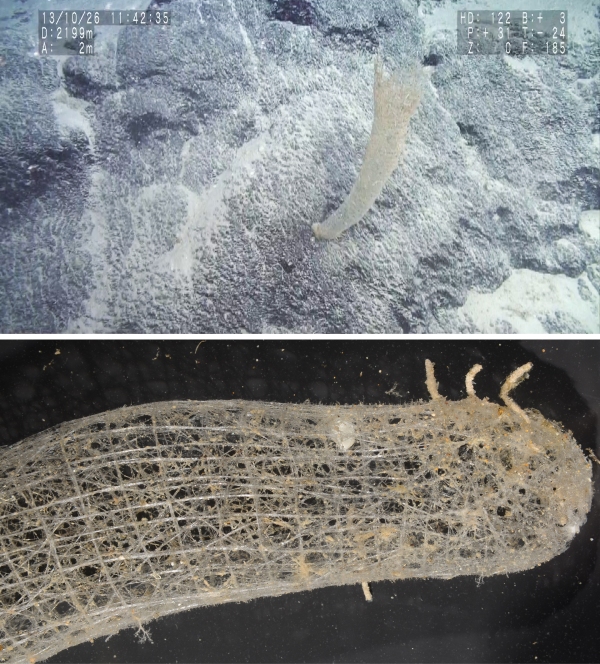

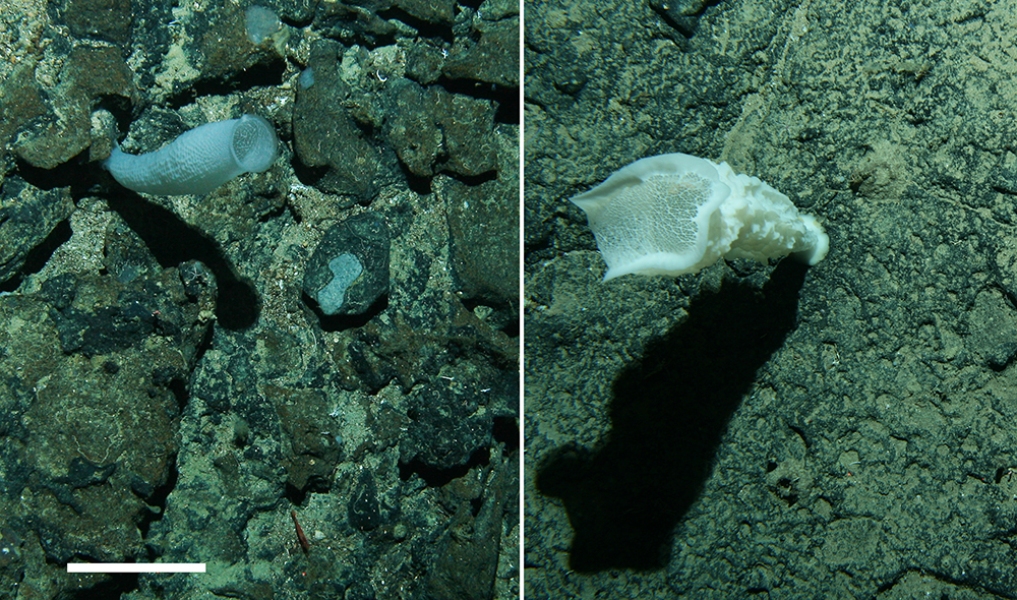

We have featured glass sponges before (e.g. CotW 40 or 112), all of them delicate and fragile and all of these share the fact that their skeleton is made of a cage of silica (glass) which is held together by thin protein filaments. There is not much else to these animals which are considered some of the most primitive life forms on earth.

This week we feature fascinating members of the hexactinellid glass sponges, the family Euplectellidae, with the common name venus flower basket. This is a widespread group that occur to depths well over 1000 m.

The common name is derived from an Asian tradition where this particular sponge (in a dead, dry state) was given as a wedding gift. This is because the sponge symbiotically houses two small shrimp, a male and a female, who spend their entire lives inside the sponge since they are too large to escape through the glass basket cage surrounding them. When they breed, their tiny offspring can escape to find a Venus Flower Basket of their own. This is apparently a mutual relationship since the shrimp probably clean the inside of the basket, which is probably food for them, and are protected from the outside by living inside the cage.

Hi-tech glass fibres

The feat of extracting silicic acid from the surrounding seawater and converting it into silica and then assembling this into a precise, three-dimensional structure is a fascinating example of biological engineering. Not only are these fibres near-perfect fibre-optic cables, transmitting light like those cables we use in telecommunication, they are also very flexible, which still defies our man-made optical fibres. So scientists are taking a close look at the way these ‘primitive’ sponges go about building their intricate baskets and can perhaps copy some of it for application.

Why would a deep-sea sponge need a light-transmitting skeleton, at depths without any sunlight? The theory is that it utilises the bioluminescent light of the surrounding, which gets transmitted throughout the sponge fibres, essentially lighting up the sponge like a ‘Christmas tree’. This possibly attracts small organism to the sponge, which then get trapped and eaten!

Watch this great video explaining this in more detail.