Tropical Cyclones

‘Trina’, the first tropical cyclone of the season

‘Trina’ developed at 21°S 160°W near Rarotonga in the Southern Cook Islands on 30 November, with estimated maximum sustained winds of 65 km/h. Winds at Rarotonga Airport gusted between 100 and 104 km/h at times between 30 Nov 0110 UTC and 1 December 2100 UTC. Some flooding was reported. The system moved northeast decaying to tropical storm intensity by 2 December 2100 UTC. The chances of tropical cyclone activity still remain slightly lower than normal for most of the South Pacific for the December–February period.

The January issue of the ICU will provide an update on information relating to any occurrences of tropical cyclones in our forecast region.

Forecasting climate – the odds on getting it right

By Alan Porteous and Stuart Burgess, NIWA

Forecasting climate is a process of looking at climate variables and weighing up the value and reliability of each piece of information. There’s no smart menu of procedures or a clever computer program that can do the job for you.

A good indicator of climate for the next few months is found in the historical climate patterns of the past 20 or more years. These tell us the likely mean state of the climate for any season or month, and the degree and frequency of climate variations on those time scales.

The natural distribution and terciles

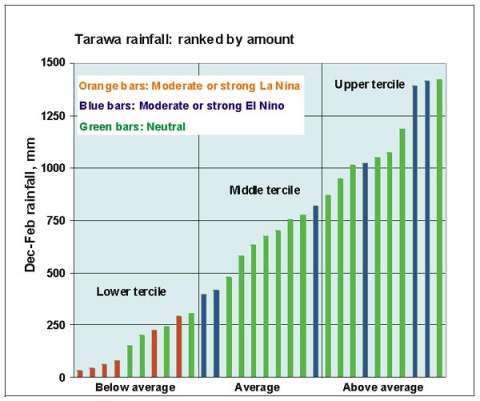

Like many natural phenomena, aspects of climate, such as rainfall amounts or mean temperatures, occur in a range of ‘sizes’ – there are high, medium, and low values. In the figure below, the last 30 years of Tarawa December through February (DJF) rainfall is arranged in order of amount (from lowest to highest), and is shown divided into three categories (terciles) with a third of the rainfalls in each category. The data are arranged into terciles simply as a way to characterise three types of period – ‘dry’, ‘average’, and ‘wet’ – that are different from each other in practical terms. So from the Tarawa data we can define a dry, average, or wet DJF period as one having less than 398 mm, 398 to 817 mm, or more than 817 mm of rain respectively. Over the long term there is a 33% chance of rainfall being in any tercile, until other factors, such as a systematic shift in circulation like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) as we will explain, tip the odds in favour of one tercile or another.

ENSO

Every now and then there is a systematic change in weather patterns – a tweak if you like in the normal circulation, affecting rainfall or temperatures, that might last for a few months or longer. ENSO is a Pacific-wide phenomenon that affects climate like that. For instance, when we examine past El Niño DJF periods in Tarawa (blue bars in the below figure), we find that on the whole they are more likely to be average or wetter than the average overall, while for La Niña (orange bars in the below figure) they are most likely to be drier than average. The dramatic influence that ENSO has on rainfall at Tarawa was seen recently in the three most recent DJF periods, which were all drier than normal.

Tarawa 1972–2001 December through February rainfall, ranked by amount, highlighting the influence of El Niño (blue bars) and La Niña (orange bars) events.

So, how would a La Niña affect our prediction of whether the DJF rainfall at Tarawa is likely to be in the top tercile (above average)? The data from previous La Niña DJF periods tells us that drier conditions are much more likely, increasing the chance from 33% to more than 90%. Conversely, an El Niño phase would decrease the chance of drier conditions from 33% to less than 10%, with average or wetter conditions more likely.

Forecast models

Just as we need to know how ENSO changes the chances of drier or wetter seasons, we have also to look at a range of other climate models and climate factors. We have to determine what physical differences in the climate they indicate are likely, and the significance of those changes. Sometimes the models can be counter-suggestive, so we must assess how much credibility or ‘weight’ to give each one. In the end, each model or climate factor offers information on how the typical distribution of climate patterns might shift, on time scales of a month or two, or a season, or longer. Climate forecasting aims to achieve a consensus that draws together all these bits of information to tell a coherent story.