Estuaries and coasts provide a wide range of benefits to New Zealanders – “ecosystem services”. However, we still don’t know enough about these ecosystem services – a challenge NIWA and other scientists are tackling with a new technique.

Overview

Marine systems provide many benefits to New Zealanders. In Auckland, for example, one is never further than 4 km from the coast, and 1 in 3 families own a boat.

We all rely on coastal ecosystems to produce:

- goods, such as fish and shellfish

- amenities

- recreation

- other crucial "ecosystem services" that support human, plant and animal populations.

While a small subset of these benefits and services are obvious, we still don’t know much about the full range.

What we know

- Marine systems provide raw materials like fishmeal for aquaculture and farming, and seaweed for fertilizer.

- Some marine organisms contain chemicals used by the medical and pharmaceuticals industries, including potentially life-saving anti-cancer compounds.

- Coastal vegetation can prevent or reduce the impacts of storms by dampening wave energy.

- Marine species are good at processing and storing human waste. For example, they can break down and transform organic waste material into inert or even useful products.

- Marine systems contain species that contribute to food webs, which in turn support top predators such as seabirds, marine mammals and humans.

- Coasts and oceans play a major role in regulating the world’s climate by balancing gas exchange and storing carbon.

In short, marine habitats provide living space for species and are vital for the provision of many of the goods and services we use.

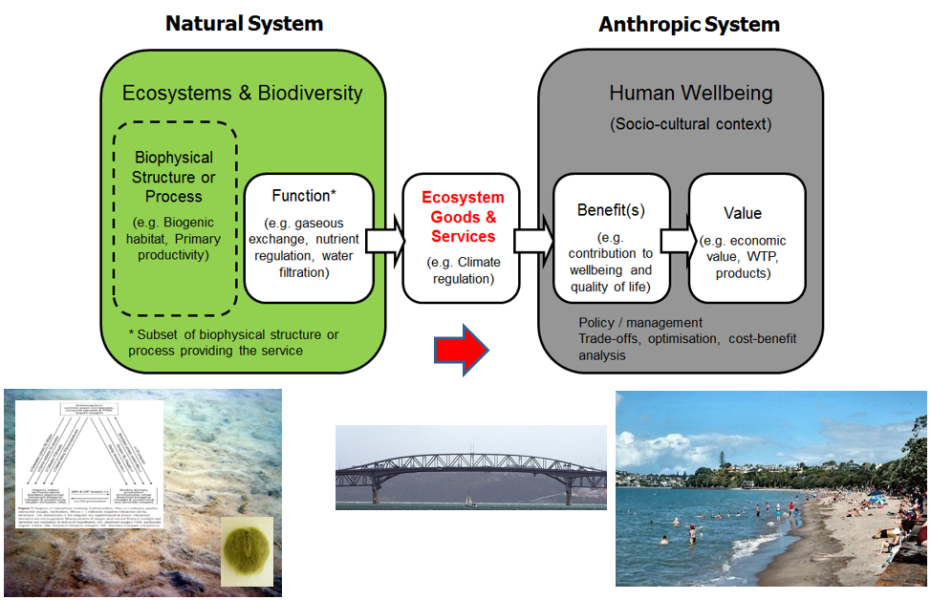

The ecosystems service concept is useful as it allows us to identify and acknowledge the underlying functions of nature that support humans (Table 1 below, Figure 2, Figure 3). Moving beyond the concept, however, there is a need to develop practical tools that use the notion of ecosystem services to improve how we manage marine resources. Marine systems are difficult to directly observe and study, making it difficult for us to know how they function. In turn, this makes it difficult to put the ecosystem services concept into practice.

Table 1: Ecosystem goods and services examples

Approach

The “Ecosystem Principles Approach”

Although there are gaps in our understanding, it is important to focus on what we do know about how marine ecosystems function, so that we can manage these systems as effectively as possible.

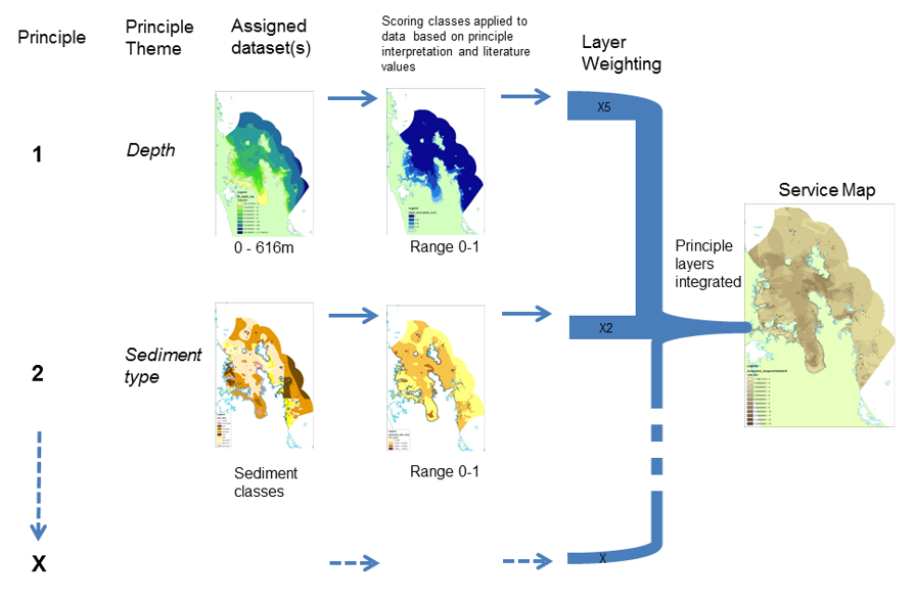

In conjunction with Auckland Council, NIWA scientists developed the ‘ecosystem principles approach’ (EPA), which helps link the processes, conditions and attributes that support ecosystem services. The EPA works by creating a list of statements that describe how ecological systems normally function when not degraded.

Examples of these principle statements include:

- “seabed productivity is greater in shallow than deeper water”

- “seabed productivity is greater in sandy rather than muddy substrates”

- “healthy areas that maintain productivity at low trophic levels should fuel high productivity at high trophic levels”.

Principle statements are then aligned with ecosystem services they relate closely to. We can use this information to figure out which habitats and conditions are important for which services. Put together, it helps us understand how to generate individual services, and the processes that are crucial for multiple services. The EPA approach has now been used in New Zealand (Auckland and Nelson) and Spain, ranging from shallow coastal systems to the deep-sea.

EPA and ecosystem service mapping

Most people don’t just want to know how ecosystem services are generated; they want to know where they are generated.

Mapping ecosystem services is difficult because we often lack detailed spatial information on seabed habitats’ distribution across most of our coastal area. This is important as these habitats can be linked to the provision of ecosystem services.

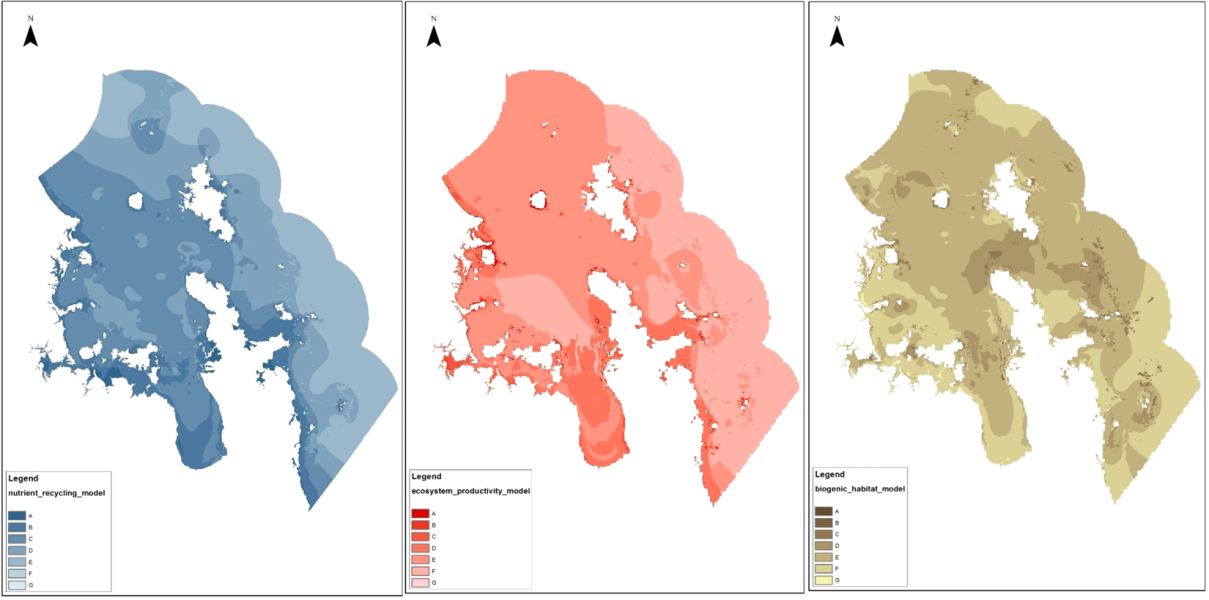

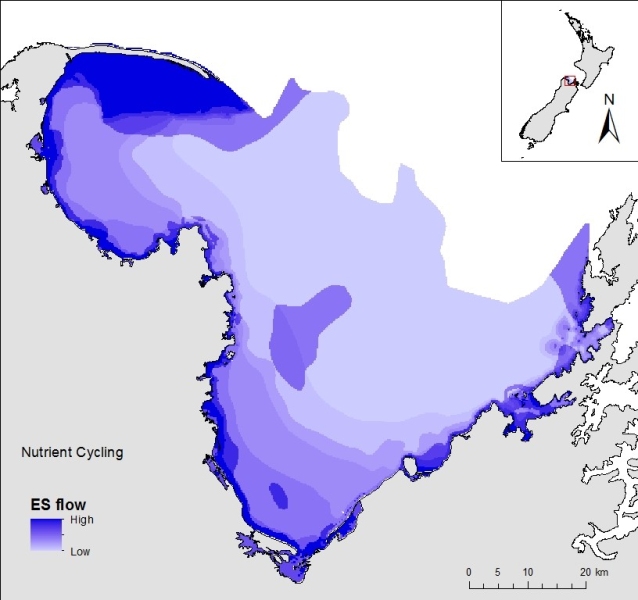

We have developed a technique for mapping ‘ecosystem service potential’. The technique uses our principles in combination with a scoring structure (for how a principle affects a service) and basic, widely available data (Figure 4). Using a ranked score approach, maps of ecosystem service potential indicate where we expect service levels to be higher or lower (Figure 1).

We have mapped three services for the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park:

- biogenic habitat provision

- nutrient recycling

- ecosystem productivity (see image to the right).

We have also started to map ecosystem service potential for nutrient recycling in the Nelson Bay area (Figure 5).

Outcome

The online SeaSketch tool for the Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan - Sea Change, Tai Timu Tai Pari - uses maps of ecosystem service potential.

Sea Change, Tai Timu Tai Pari: Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan

The tool allows users to think about ecosystem services as they explore the conservation, economic, social and cultural uses of the Hauraki Gulf. By considering ecosystem services, we can make more informed decisions.

The tool has been used to identify and communicate the ecological value of deep-sea ecosystem services. A key part of this has been broadening access to ecological knowledge for decision makers.

Outputs

Our research in the field of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services has produced technical reports and papers from a number of scientific research studies.

- Thrush SF, Townsend, M. et al. (2013) The many uses and values of estuarine ecosystems, in ‘Ecosystem Services in New Zealand’ – Condition and Trends, Edited by John Dymond, Landcare Press

- Townsend, M.; Thrush, S. (2010). Ecosystem functioning, goods and services in the coastal environment. Prepared by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research for Auckland Regional Council. Auckland Regional Council Technical Report 2010/033 [PDF 1 MB]

- Townsend M., Thrush S.F., & Carbines M. (2011) Simplifying the complex: an ‘Ecosystem Principles Approach’ to goods and services management in marine coastal ecosystems. Marine Ecology-Progress series, 434, 291-301

- Jobstvogt N, Townsend M, Witte U, Hanley N. (2014) How Can We Identify and Communicate the Ecological Value of Deep-Sea Ecosystem Services? PLoS ONE 9(7): e100646

- Needham, H. Townsend M., Hewitt J. Hailes, S (2013) Intertidal habitat mapping for ecosystem goods and services: Waikato Estuaries. Waikato Regional Council Report, TR2013/52

- Michael Townsend, Simon F. Thrush, Andrew M. Lohrer, Judi E. Hewitt, Carolyn J. Lundquist, Megan Carbines, Malene Felsing (2014) Overcoming the challenges of data scarcity in mapping marine ecosystem service potential. Ecosystem Services, 8: 44–55

- MacKenzie L, Townsend M, Clark D, Ellis J, Thrush S (2014). Inventory of coastal ecosystem services in Nelson Bays: Nutrient cycling. In Integrated Valuation of Coastal-Marine Ecosystem Services, Book Chapter 3

- Sea change: Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan. “SeaSketch layers live now”

Table 1: Ecosystem goods and services examples

|

Over-arching categories |

Ecosystem goods and services |

Examples |

|

Provisioning services |

Food provision |

Snapper and cockles to eat |

|

Raw materials |

Seaweed fertilisers | |

|

Genetic and medicinal resources |

Anti-cancer drugs from sponges | |

|

Regulating services |

Disturbance prevention |

Storm protection by mangroves |

|

Waste treatment, processing and storage |

benthic animals breaking down sewage | |

|

Water regulation |

Regulation of drainage by saltmarshes | |

|

Sediment retention |

Seagrass helps retain sediment | |

|

Biological control |

Marine predators regulate food webs | |

|

Gas and climate regulation |

The balance of carbon dioxide between sea and air | |

|

Nutrient regulation |

Recycling of nutrient by benthic animals | |

|

Supporting services |

Resilience and resistance |

Absorbing human pressures and recovering quickly |

|

Habitat structure |

Kelp reef provide living space and food for other species | |

|

Cultural services |

Cultural and spiritual heritage |

The importance of the marine environment for determining who we are, our identity |

|

Leisure and recreation |

Beach walks, kayaking, diving, nature tours | |

|

Cognitive benefits |

Education and scientific research | |

|

Non-use benefits |

Contentment that marine creatures are alive and may be experienced by future generations | |

|

Speculative benefits |

Possible uses in the future | |

External people involved:

Megan Carbines (Auckland Council)

Hilke Giles (Waikato Regional Council)

Simon Thrush (University of Auckland)