Priceless or pestilent? Your view of mangroves, finds Greta Shirley, often depends on how many mangroves are in your view...

The Coromandel is well-used to raging debate over native forests, usually because they were disappearing. But in the township of Whangamata, the argument isn't so much about a vanishing flora, as a burgeoning one.

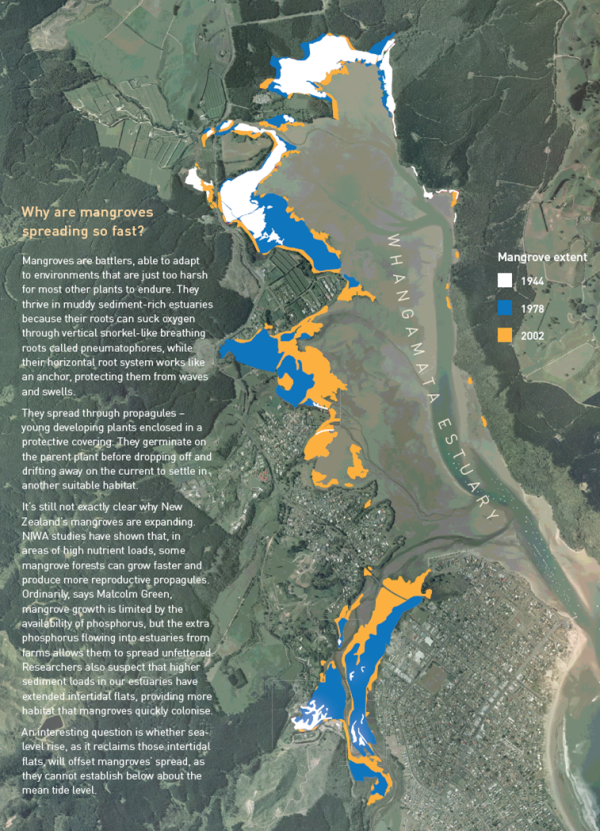

Mangroves are on the march. Around here, as in much of the upper North Island, they've thrived on the extra sediment washed down from cleared hills and felled forests. In the 1940s, small patches of mangroves covered around 24ha along the edges of Whangamata Harbour. Today, thickets of the salt-loving native shrub sprawl across some 100ha, raising the ire of many locals who feel they're smothering the harbour's aesthetic and recreational values.

They regard mangroves as a weed: an eyesore and a hazard, hindering access and marring views, lowering fish catches and property values alike. But others say nature should be left to its own devices, and warn that removal or control of the mangroves will have irreversible consequences for the harbour ecosystem, destroying important habitat for fishes and birds, and triggering still more coastal erosion.

Emily O'Donnell has heard every claim, every plea, every rebuttal. Harbour and Catchment Management Coordinator for the Waikato Regional Council (WRC), O'Donnell has spent close to a decade helping the people of Whangamata find an accord. "Both sides of the argument come from a real place of passion," she says. "The scale of removal ... is at the heart of the debate."

In 2005, frustrated by what they saw as regional council inaction, 120 locals took matters – and chainsaws – into their own hands. Twice, they illegally cleared a swathe of mangroves in the harbour, one the size of two rugby fields.

When former local MP Sandra Goudie weighed into the protest, it made national headlines. Goudie, who copped heavy criticism for her involvement in the illegal clearance, said it was a wake-up call for regional politicians: "These people are sick of the political correctness. They don't mind a bit of oversight or a few guidelines, but they just want tools to manage it, or they want (the then) Environment Waikato to manage it."

O'Donnell agrees: "Part of the angst is just how long it's gone on for. For some of these people, it's been a 13-year discussion – they want to see action."

Some of them have been holidaying or living in Whangamata for 40 or 60 years in some cases ... they know the harbour intimately. It is where they go daily, to fish or gather shellfish, and a lot of them are genuinely interested in the natural environment. They feel that a lot of those values are being eroded by mangrove expansion."

Local Whangamata resident and environmental scientist Dr Brian Coffey has spent more than ten years providing scientific support to Whangamata Harbour Care – a group of 60 or so passionate local residents helping manage the mangroves. They've successfully applied for resource consent to clear some small patches themselves.

Coffey says past abstention by regional councils has resulted in ad hoc attempts to control and manage mangrove spread across the upper North Island – some illegal, some consented.

"Groups like the Pahurehure Protection Society, the Mangawhai Harbour Restoration Society, the Waiuku Ratepayers Association and Whangamata Harbour Care began advocating for mangrove management in the late 1990s," he says. "They were left to their own devices and funding sources to get consents to undertake experimental removal, or get their hand-weeding consents, and then there were some locals who took it upon themselves to get in and clear areas on their own."

In the early 2000s, says Coffey, regional councils finally addressed that ad hoc process with formal harbour and estuary management plans that also tackled the causes of mangrove spread, such as sedimentation and nutrient run-off.

Good science then became critical, he says. "If mangrove management is done as part of a comprehensive harbour or catchment management plan, that's got to be sciencedriven. It needs to be looked at as a holistic management effort – well-coordinated, well-planned and wellresourced, addressing all the issues – not a ragwort control programme, which is how the locals previously viewed it."

NIWA is working with a number of regional councils and local community groups to develop best practice for mangrove management, and monitoring the effects where mangroves have been removed. Researchers are currently looking at what drives mangrove spread (see 'Why are mangroves spreading so fast' at the end of this article), understanding more about the ecological functions of mangrove habitats, and how mangroves might respond to sea-level rise.

Choosing between stopping or suffering the spread of mangroves isn't really a science argument, says NIWA Principal Scientist, Dr Malcolm Green. "To me that's a values argument. It's about how people want their estuaries to be." Rather, he says, science can help answer questions around whether removal will be effective in certain areas, and what the ecological impacts might be.

"Pick the battles that you are going to win and the ones you should stay away from." Each setting is unique, and will not respond to intervention in the same way, he says.

"Overseas research shows that tropical mangroves are hugely productive, and provide habitat for birds, fishes and all kinds of invertebrates. No doubt they have some function like that in New Zealand, but I don't think we really understand the scope of that very well yet. We need to keep working on it."

It's important to look beyond the harbour to the catchment, says Green: "If you don't control the sources of sediment – and possibly nutrients – that cause mangrove spread, then you can pull them out until your heart's content and they're just going to come back."

The WRC has done just that. Mangrove control is now part of their wider harbour and catchment management plan. After years of community consultation, scientific research and environmental assessment reports, the Council last year applied (to itself, ironically) for resource consent for the staged removal of 31ha of mangroves from Whangamata Harbour. The application attracted 180 submissions, with only eight opposed. Independent commissioners agreed that staged removal could go ahead, but not before environmental monitoring and operational plans are in place, and then only over half that acreage: 16.5ha of new removal and some additional tidying up.

O'Donnell, who's managing the consent application, believes the Council's adaptive management approach made a compelling case, but "the commissioners have proceeded with extreme caution. They seemed to feel that there wasn't enough evidence to support any further removal," she says. "There was concern around impact on banded rail habitat and ... what impact that quantum of removal would have on the harbour."

Having waited 13 years, Whangamata locals face another delay, however: the consent was appealed by Forest and Bird, who say only 1.72ha should be removed, mainly for maintaining drainage channels. The Council has counterappealed, seeking clearance of the original 31ha. The debate is possibly headed for the Environment Court.

Despite the uncertainty and delay, says Coffey, it's good that the WRC has taken responsibility for Whangamata's mangroves, and taking that broader catchment approach has moderated local attitudes to them.

"I don't think it's a divisive issue for the community now – the locals are pretty much of one mind. They're not advocating complete clearance of mangroves from any harbour. It's a matter of keeping a balance, to stop further spread, and having some objective basis for deciding what proportion of the mature established mangroves can be removed without any adverse ecological effects."

Coffey says Whangamata has become a test case for those opposed to mangrove clearance. "People coming in from the outside tend to be more vocal against it, to be honest. The illegal clearance became high profile, so it's become quite important for Forest and Bird and others ... to make an example of Whangamata I think."

Large-scale mangrove clearance has had a chequered history. Over 2010, the Bay of Plenty Regional Council (BOPRC, formerly Environment Bay of Plenty) mulched 80ha of mangroves around Welcome Bay, in Tauranga Harbour, with a tracked machine. The mulch was left lying on the mudflats in the belief that it would 'mobilise' – or drift away on the tides. However, the mulch proved stubbornly immobile, and hectares of harbour reeked with rotting mangrove debris. Concerns were raised that the mudflats beneath would be smothered. NIWA scientists are now helping the Council assess the ecological impacts and potential recovery measures. BOPRC resumed the clearance in January 2011, but afterwards picked up the mulch.

Tauranga offered a cautionary tale for other councils. "We're grateful that we were able to learn from the Tauranga experience," says O'Donnell. Until the Welcome Bay operation, WRC had been considering mechanical mulching in the Whangamata Harbour, but reconsidered after seeing the impacts.

"It's provided quite a catalyst for us to investigate other options. BOPRC has been really forthcoming with information to us. It's provided an opportunity for a whole lot of dialogue between the councils around options we were looking at. We, like others, were under the impression that the mulching would mobilise quite quickly, but obviously it didn't do that."

Adding science to the debate usually softens peoples' views, says Green. His first few exchanges were with community groups who wanted every last mangrove pulled out. But, he says, after only short discussion "you could see people shifting their position, realising that's not desirable, but also it's not practical either. There's a middle ground there now, and Whangamata has been a good example of that."

O'Donnell gives a wry laugh at the suggestion: "There are opportunities for more learning on all sides, and to look at how we communicate and share the information." She says it's critical to look at mangrove management "under the umbrella of the wider harbour and catchment management plan, so that we address the wider issues too. Better that, than being the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff."

End

Isn't it ironic?

Mangroves of one sort or another have lined stretches of New Zealand coast for at least 19 million years. Avicennia marina, or manāwa, our only present-day species, is thought to have arrived here about 11,000 years ago. Traditionally utilised by Māori for food, fuel and medicine, mangroves reach the stature of small trees in the far north, but shrink to shrubs further south. They don't occur – naturally, at least – any further south than Ohiwa Harbour on the east coast of the North Island, or Kawhia on the west.

While New Zealand mangroves are currently spreading at around an estimated five per cent each year, they've been decimated overseas. Globally, mangroves have disappeared from about half their former range – mostly stripped for timber, fuel, medicine and food – to become one of the most threatened natural community types.

Recognising their role in coastal protection, water quality, wildlife and fisheries habitat, and tourism, many countries now spend millions each year on mangrove conservation, restoration and management. Of the 90 countries that have mangrove vegetation, around 20 are involved in rehabilitation initiatives.

Why are mangroves spreading so fast?

Mangroves are battlers, able to adapt to environments that are just too harsh for most other plants to endure. They thrive in muddy sediment-rich estuaries because their roots can suck oxygen through vertical snorkel-like breathing roots called pneumatophores, while their horizontal root system works like an anchor, protecting them from waves and swells.

They spread through propagules – young developing plants enclosed in a protective covering. They germinate on the parent plant before dropping off and drifting away on the current to settle in another suitable habitat.

It's still not exactly clear why New Zealand's mangroves are expanding. NIWA studies have shown that, in areas of high nutrient loads, some mangrove forests can grow faster and produce more reproductive propagules. Ordinarily, says Malcolm Green, mangrove growth is limited by the availability of phosphorus, but the extra phosphorus flowing into estuaries from farms allows them to spread unfettered. Researchers also suspect that higher sediment loads in our estuaries have extended intertidal flats, providing more habitat that mangroves quickly colonise.

An interesting question is whether sealevel rise, as it reclaims those intertidal flats, will offset mangroves' spread, as they cannot establish below about the mean tide level.

See the image in the right hand side bar (click to enlarge) to see the extent of the spread.