Where and when do white sharks occur in New Zealand waters, and how can fisheries bycatch be reduced?

Problem

Why do we want to tag white sharks?

White sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) became a protected species in New Zealand waters in 2007, but many of them are still caught incidentally each year in set nets and other fishing gear.

The status of white sharks in New Zealand is unknown, but because of their low reproductive and growth rates, there is concern that fishing mortality may be causing a population decline. Little is known about the habitat requirements of white sharks, their seasonal behaviour patterns, or their interactions with fisheries. An improved understanding of where they are at what times, and their migratory patterns would allow strategies for reducing bycatch to be developed

Solution

Hi-tech electronic tags

A joint NIWA/Department of Conservation (DOC) tagging programme was launched in 2005. Hi-tech electronic tags are being used to gather information on where the sharks are and when, and to record their depth and the temperature of the surrounding water. Three tag types have been used: popup archival tags, acoustic tags, and dorsal fin tags.

Popup tags

Popup tags are implanted in the muscle under the dorsal fin with a tagging pole, and record depth, temperature and location, storing the data for up to a year. They then release themselves from the shark, float to the surface, and transmit summaries of the data to a satellite. If the tags are physically recovered, the high resolution data collected at one minute intervals can be downloaded.

Popup tags provide only approximate location data, so they are most useful for tracking long-distance migrations.

Acoustic tags

Acoustic tags send out coded, individually identifiable sound ‘pings’ that can be detected up to a kilometre away by acoustic data loggers. The tag batteries last long enough to monitor the presence of white sharks in the region in the vicinity of a data logger for two years.

Acoustic tags provide accurate fine-scale information on sharks at specific locations.

Dorsal fin tags

Dorsal fin tags bridge the gap between popup and acoustic tags. They provide accurate location information by transmitting to orbiting satellites every time the shark is at the surface and the dorsal fin and the tag’s aerial are exposed to air. Their batteries can last for more than one year, so both fine scale and large scale movement patterns can be recorded.

However, dorsal fin tags are more difficult to deploy: the shark has to be caught and restrained while the tag is attached to the dorsal fin. So far, only a few of these tags have been deployed in New Zealand.

See our 'Shark tagging' photo gallery

Outcome

New insights into the behaviour of white sharks

Since 2005, 44 white sharks have been tagged with popup tags, mainly at the Chatham Islands and Stewart Island. These islands support large colonies of fur seals, which are a major food source for white sharks. Our research has focussed on Stewart Island since 2009. The population there is dominated by males (about 2.2 males for every female). Nearly all of the females are immature, being shorter than the female length at maturity of 4.5 to 5 m. Only about one-third of the males are longer than the male length at maturity of about 3.6 m. This indicates that the white shark aggregations at Stewart Island are not related to mating, and are most likely driven by the abundance of seals for food. Large, mature females are rarely seen anywhere in New Zealand and their distribution, habitat and behaviour are almost completely unknown.

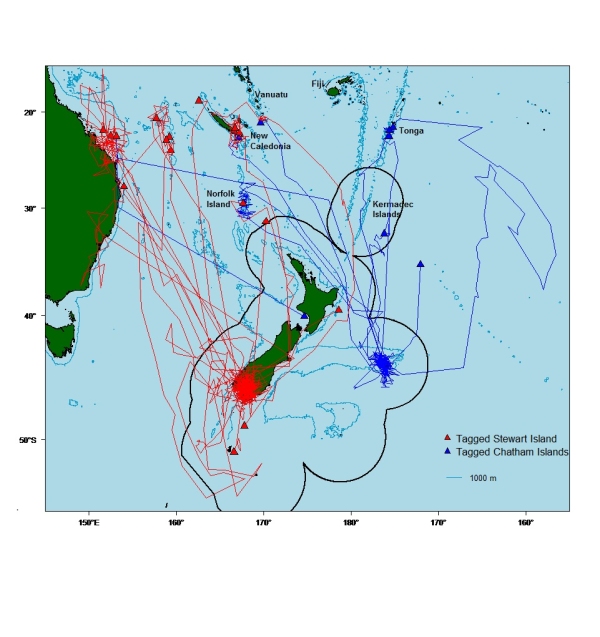

Tagging results (click righthand map to enlarge) show that most New Zealand white sharks make annual migrations to tropical waters in winter, travelling as far as 3,300 km away. Sharks have migrated to the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, the Coral Sea, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Norfolk Island, Fiji and Tonga. They don't cross the equator.

Most of the sharks from Stewart Island headed northwest of New Zealand, whereas most Chatham Islands sharks headed north. However, some sharks from the two tagging locations overlap in the tropics. Surprisingly, we have not detected any direct movement between Stewart and Chatham islands.

Some popup tags have remained on the sharks for long enough (up to one year) to reveal that the sharks returned to their tagging locations after their tropical holiday. This has been confirmed by photo-identification work at Stewart Island. Each shark has a unique colour pattern, particularly around the gills and on the tail. Some individuals have been seen at Stewart Island each year for multiple years. This indicates that white sharks have a sophisticated navigation mechanism that enables them to make major direct oceanic migrations, and then return to precisely the spot they left from. We do not know how they achieve this.

During their travels, white sharks experience a wide range in temperatures, from 3 degrees C to 27 degrees C: very unusual for a fish. During their ocean crossings, they can travel 150 km per day, and average about 5 km per hour or 100 km per day.

They spend two-thirds of their time at the surface, and the rest making repeated deep dives to 200-800 m. Most sharks reach maximum depths exceeding 800 m, and the record depth achieved was 1,246 m. We do not know what the sharks are doing in these depths - where there is no light - but we presume that they are searching for prey such as deep water squids and fishes. They may also be searching for the many north-south running undersea ridges to use as a navigational aid.

Now that the large-scale migrations of white sharks are better understood, the focus of the research has shifted to determining their fine-scale movements and local temporal and spatial distributions. In March-April 2011 and 2012, 45 white sharks were tagged with acoustic tags around north-eastern Stewart Island, and 25 data loggers were deployed at strategic locations around northern Stewart Island, Ruapuke Island and Foveaux Strait. White sharks were present almost continuously from late summer to early winter, peaking in autumn (March−June). Sharks spent about 4−5 months in the region and the rest of the year outside New Zealand on their tropical migrations. Some of these sharks were detected in Australia and the Coral Sea by data loggers deployed by other researchers. White shark abundance was greatest in the Titi (Muttonbird) Islands off northeastern Stewart Island, and sharks showed different preferences for individual islands. Stewart Island sharks rove well beyond their aggregation sites, but the behaviour and dynamics of white sharks in other parts of New Zealand remain poorly understood.

Dorsal fin tags were attached to three sharks in 2013 and 2014, giving us unprecedented accurate information on their movements and the routes taken. One shark (nicknamed Nicholas Cage) swam to New Caledonia in an almost straight line and then ‘disappeared’ underwater for several months, before re-surfacing and making a more-meandering return trip to Stewart Island. Another shark (Pip) swam across the southern Tasman Sea to New South Wales in Australia, and then made her way north to warmer Queensland waters, before returning to Stewart Island. The third shark (Caro) swam north up the central Tasman Sea to the Coral Sea and Queensland before returning to Stewart Island.

The final phase of this study will be to compare information gained on the seasonal and spatial distribution of white sharks in New Zealand waters with the distribution of fishing effort to identify locations and seasons where there is a greater risk of sharks being caught by fishing gear.