Coastal communities around New Zealand are getting a say on how to respond to sea-level rise, and NIWA is helping them.

Discussions about the impact of sea-level rise on our coast have revealed the deep difficulties in communities agreeing on whether, and how, to respond to changes.

There has been intense community resistance to local authorities identifying, labelling and controlling homes at risk of flooding from rising sea levels.

Now though, moods are changing as new approaches are taken to discuss the threats forecast from climate change.

This shift was marked in December last year by the release of the Ministry for the Environment’s (MfE) ‘Coastal Hazards and Climate Change – Guidance for Local Government in New Zealand’ in December 2017.

The guidance recommended a “dynamic adaptive” approach to planning. The approach is less severe and top-down, and more consultative and consensus-based. This is less threatening to those who face the bulk of adaptations, and more accommodating of small, regular adjustments over a longer period.

A benefit of the approach is the decisions and investments made now can accommodate future changes required by the still uncertain rate and scale of impacts from climate change.

Scenario planning

The Guidance provides four sea-level rise scenarios out to the year 2150 which can be used to plan for fast, slow, or intermediate rates of sea-level rise.

At its heart is a 10-step decision-making approach, to plan and adapt to rising seas. It addresses “What is happening?”, “What matters most?”, “What can we do about it?”, “How can we implement the strategy?” and “How is it working?”

Dr Scott Stephens is a Coastal and Estuarine Physical Processes Scientist at NIWA, and one of the Guidance authors. He says the Guidance combines a step-by-step approach to assessing, planning and managing the increasing risks, with updated information, tools and techniques.

“The approach improves on previous guidance and current coastal hazard management practice in its treatment of uncertainty and the central role of community engagement in the decision-making process.

“The new guidance is a major revision of the 2008 version. It includes updated sea-level rise projections, advances in hazard, risk and vulnerability assessments, collaborative approaches to community engagement and changes to statutory frameworks.”

Essentially this reflects an appreciation that sea levels are rising, but the seriousness of impacts is still unknown.

“The Guidance provides methods that can be used for decision making under deeply uncertain conditions about the future, such as how fast sea level will rise, or how community coping capacity and vulnerability will change,” says Dr Stephens.

The local word

Hawke's Bay is one of the first regions to apply the 10-step decision cycle in the MfE Guidance. The region has had its share of historical controversy and conflict as residents have grappled with the implications of sea-level rise.

The latest efforts, focused on the development of the Clifton to Tangoio Coastal Strategy, have been more successful. This has been facilitated by the combined councils of Hawke's Bay and a team from consultants Mitchell-Daysh.

Dr Paula Blackett is a NIWA Environmental Social Scientist and one of several social scientists on the interdisciplinary team working on what Hawke's Bay has dubbed the ‘Living at the Edge’ project.

She says the format has enabled a decision cycle that was “specially designed to work in situations of conflict where contested values and uncertainty dominate conversations”.

To support the Clifton to Tangoio Coastal Strategy development, Blackett is acting as a ‘critical friend’ which she describes in this case as “essentially an independent research team providing supporting knowledge, ideas and thinking, and constructively highlighting problems and dilemmas to be resolved.”

She says the contribution of social scientists has been essential.

“The purpose was to provide timely feedback that illustrated how the community participants perceived the process and progress at each event or workshop, and to identify any potential issues and challenges before they became more substantial issues.”

Chair of the strategy development process, Hawke's Bay Regional Council Councillor Peter Bevan says that the bottom-up approach was essential.

“Those who find themselves threatened by coastal hazards need to be closely involved in any response strategy. That is why we adopted a bottom-up strategy in Hawke's Bay.

“Any local body that adopts solutions that have not been extensively consulted will risk prolonged conflict and argument.”

Dr Blackett says that early engagement of the community is both possible and fundamental to developing climate change adaptation strategies.

“This work has shown how the Guidance can succeed in practice through a combination of well-thought-out processes, technical science support and attention to the social and economic aspects of coastal adaptation.”

She notes that overall, the stepped process created time and the space for people to talk through the issues and conflicts, to consider all the options and to think in a long-term, strategic and dynamic way about the challenges ahead.

“In short, it empowered them in a way which has not been attempted previously.”

Informed decisions

The Deep South National Science Challenge is another initiative delivering valuable scientific knowledge communities can use in their decision making. Part of the NIWA research funded by the challenge is to estimate storm-tide levels around the New Zealand coast based on a one percent annual chance of these levels being reached or exceeded.

Ryan Paulik, NIWA Hazards Analyst, explains that these levels are projected onto land to create individual storm-tide hazard exposure maps for the present-day hazard, and future sea-level rise scenarios, using increments of 0.1m up to 3m above mean high water springs.

“This work extends an earlier project for the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment in 2015 by including storm-tide hazards in sea-level rise inundation maps,” he says.

“The incremental sea-level rise scenarios enable these maps to be matched to future sea-level rise projections. This provides both spatial and temporal estimates for asset exposure to inundation from sea level rise and storm-tide hazards in New Zealand.”

Paulik considers that the relationships between research institutes, such as NIWA, and academic and government organisations are critical to delivering robust science.

“Universities and Crown Research Institutes like NIWA provide the capacity to develop new and innovative modelling techniques to estimate New Zealand’s exposure and vulnerability to future impacts from natural hazards.”

Knowledge shared

Over the next few months MfE will hold workshops around the country with regional and local authority staff to help them understand how to use the guidelines.

Dr Scott Stephens is part of the team facilitating the workshops.

He says they will help “familiarise users with the Guidance, explaining context, key features, how it interacts with the statutory (legal) framework, advice on conducting sea-level rise, hazard, risk and vulnerability assessments, and advice on community engagement processes”.

“The workshops will demonstrate the application of dynamic adaptive pathway planning methods, step-by-step and with exercises.”

The workshops are another example of a shift in approach that will help coastal communities become better prepared for rising sea levels, and provide them knowledge they can use to make practical adaptations.

The floating Sea Scout hall

Based on the coastline of Wellington’s Evans Bay, the Britannia Sea Scouts are currently considering solutions for their hall, which has frequently flooded during king tides and storms over the past six years.

The club’s chairperson Inger Deighton says the hall has sometimes been saturated by up to 30cm of sea water, which enters through the floor boards.

“The latest casualty has been our gas oven after its pipes rusted from the frequent flooding. Other items we have lost have been our water blaster and vacuum, as well as really anything that has been on the floor of the hall.

“One storm the hall was actually lifted off its pilings, which parents attempted to fix by strapping the piles to the floor boards as a temporary solution,” she said.

The initial solution was to raise the hall by 30cm, however consultations with NIWA have indicated that this will only solve the issue temporarily as sea levels continue to rise.

According to NIWA Principal Scientist Dr Rob Bell, the frequency at which low-lying coastal areas are flooded is increasing as sea levels rise, which have already risen by 23cm over the last 100 years in Wellington.

“I’ve noticed over the years I have been visiting NIWA's Wellington campus at Greta Point that the tide reaches the boatshed floor level more often.

“The sea level is also rising faster in Wellington as the lower North Island is subsiding by 2–3mm per year due to seismic slow-slip of plates.”

NIWA have also found that the already risen sea level has resulted in a change in frequency of 100-year storm-tides.

“For Wellington, it will only take a modest sea-level rise of 30cm for this rare storm-tide level to be reached once a year on average.”

“This also means spring tides and smaller storm tides will be higher and more often – as observed at the boat sheds,” said Dr Bell.

As the battle with Mother Nature continues, the Sea Scouts are feeling under pressure to decide the fate of their hall. The irony of one option has not escaped them; that the Sea Scouts will need to build a new hall further away from the sea.

Mapping floods

Digital mapping of flood prone areas is enabling local communities to gain a clearer picture of vulnerabilities to flooding caused by a changing climate, and what to do about it.

One fascinating study is mapping where flooded roads could lead to floating cars.

Ryan Paulik, NIWA Hazards Analyst, was part of a NIWA team reviewing international literature on vehicle stability in flood flows.

“Laboratory studies have demonstrated that hatchback or sedan models can float in water depths as little as 0.3m, compared with 0.45m for SUVs.”

“With this information, we are able to use high resolution flood maps to identify roads and locations inundated by flood waters that are dangerous for vehicle traffic.”

The open access software RiskScape, developed by NIWA and GNS Science, provides a framework to estimate impacts and material losses, from floating cars to saturated houses. The team used the data from the Christchurch City flood event in March 2014 to identify a prevention method that could reduce losses by 70% in future events.

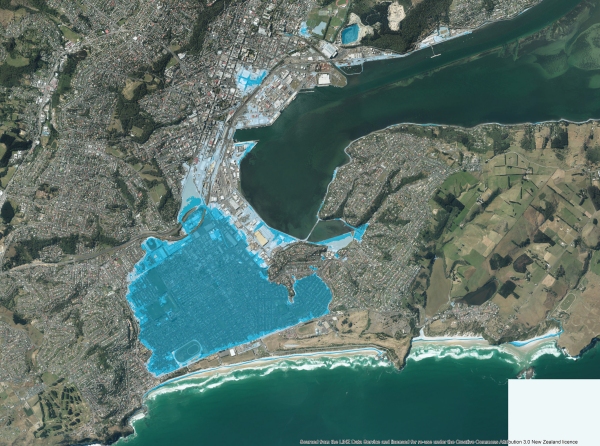

In South Dunedin, a new multi-layered database is producing digital maps showing how forecast sea-level rise will cause flooding in the area from rising groundwater combined with rainstorms and elevated storm-tide levels.

The maps are a collaborative effort by the University of Otago’s Centre for Sustainability, the Dunedin City Council and the Otago Regional Council.

The maps allow better demonstration of the impact because they combine details held by different agencies, such as demographics and house ages.

Auckland Transport has used NIWA-developed inundation maps to identify the replacement value of roads that could be exposed to coastal flood events under future sea-level rise scenarios.

Auckland Council is working with Auckland Transport to identify the most vulnerable assets and hot spots where future planning and adaptation work can be targeted. The information has been made publicly available through the Auckland Council’s GeoMaps online mapping service.