The on-going rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) that is fuelling climate change is also driving significant changes in the waters off our coasts.

Rising seas are the most obvious sign of this greenhouse gas-powered transformation. But equally dramatic—if somewhat less visible—are the changes occurring in the ocean itself.

More than 90 percent of the excess heat generated as a result of global warming has been absorbed by the oceans, and about 40 percent of the C02 produced by humans in the past 50 years has ended up in our seas.

NIWA research confirms that our oceans are getting both warmer and more acidic, and scientists are now focusing on how these changes threaten the delicate balance of life beneath the waves.

It’s getting hot out there

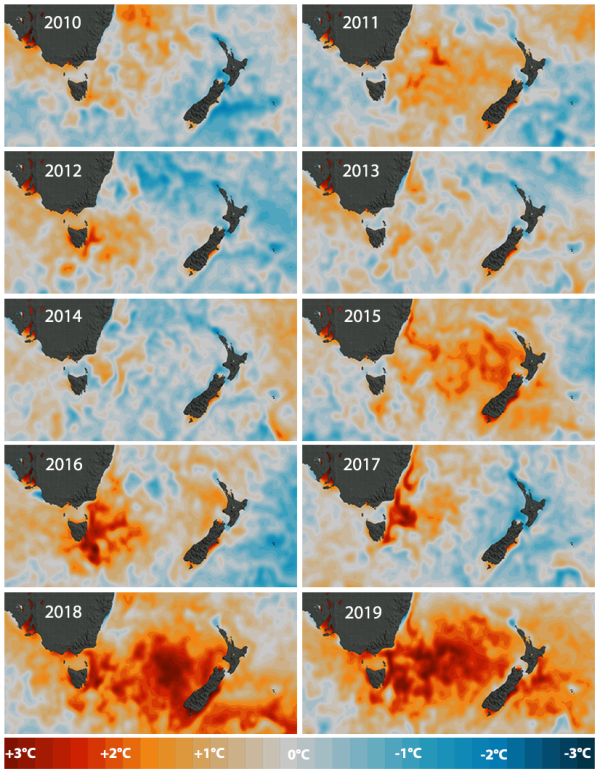

Research released earlier this year by NIWA oceanographer Dr Phil Sutton reveals the surface waters in the New Zealand region are significantly warmer than they were 30 years ago.

Our marine environment has seen a warming of about 0.1°C to 0.3°C per decade. This seemingly small rise has already contributed to record sea surface temperatures recorded in the Tasman Sea in the past two years.

NIWA Principal Scientist Dr Craig Stevens says this ocean warming is undoubtedly damaging for marine ecosystems.

“Species that normally live in tropical waters are extending their ranges and displacing other species. Mobile marine life can escape the warmer temperatures, but sedentary plants and animals will be hardest hit. The impacts are there for aquaculture as well, with warmer waters making it more difficult to grow some finfish or shellfish.”

Increasing marine heatwaves are an indication that the earth’s climate system is starting to change.

“Individual warm seasons have always occurred, but in future there will be more of them and they will keep getting warmer,” Stevens says.

“And a sobering thought is that even if we somehow managed to turn global warming off right now, the atmosphere would keep warming for some years to come because of the heat that’s stored in the ocean.”

Bad acid trip

The on-going rise in greenhouse gases is also acidifying the waters around New Zealand. As the oceans absorb more C02, the pH of the water changes, becoming more acidic through a process known as ocean acidification.

NIWA’s Dr Kim Currie, in partnership with the University of Otago’s Department of Chemistry, has been tracking this gradual acidification of waters off the coast of Otago for almost 20 years. The study, the Munida Transect Time Series, is the Southern Hemisphere’s longest-running record of pH measurements.

“Through this work, we’ve established a clear decline in pH that corresponds directly with the increase in atmospheric C02 recorded at NIWA’s atmospheric research station near Wellington,” says Currie.

Shellfish, cold-water corals and some algae and plankton struggle to produce shells as the pH decreases, and the NIWA-led CARIM (Coastal Acidification: Rate, Impacts and Management) project is looking at how marine organisms will cope with this changing pH.

CARIM is a partnership between central and local government, the fishing industry, science organisations, iwi and other community groups. It is examining the effects of acidification on primary production, food quality and habitat availability in New Zealand coastal waters.

CARIM has a particular focus on the sensitivity of the different life stages of iconic New Zealand species including pāua, greenshell mussels and snapper larvae.

Project lead and NIWA Principal Scientist Dr Cliff Law says a key part of the programme is finding out whether coastal areas are resilient or will be vulnerable as ocean acidification intensifies.

“We know coastal waters are the most variable in their natural pH levels. They are where we gain the most benefits in terms of food, recreation and other amenities, yet it’s also where we impact the ocean most.

“We are building our knowledge of ecosystem interactions, which is critical for developing models and projections. These tools and solutions will help us mitigate and adapt to ocean acidification.

“The outcome of CARIM will be better models, allowing more accurate predictions of the impacts of acidification in coastal waters, as well as potential management options.”