The summer rain came early to Tasman. It fell as light showers at the beginning of December, stopped for a while, and then came back steady and heavy for about a week before Christmas.

So much rain so soon in the season made Richard and Jan Fenton a happy pair. The water tanks on their Upper Moutere farm were full, the sheep were munching on lush paddocks and there was virtually no wind.

“That is very appealing when you come from Canterbury,” says Richard.

Then it all changed. It rained on Christmas Day, but that was it. There would be no more rainfall of any significance for 71 long days.

Without the rain, soil moisture levels dropped rapidly across Tasman and the wind picked up. By the end of January, NIWA soil moisture probes were reading below wilting point, the level at which it is difficult for plants to survive.

Water restrictions were enforced with ever-increasing severity, but the Fentons were coping after taking prudent storage measures. Jan was also capturing water from the sink and shower in a vain attempt to keep her vege garden going.

Richard drove to Christchurch and brought back lucerne for the sheep. Some farmers were starting to use their winter feed.

As the constant hot wind killed the grass and left hectare after hectare of hillside forests tinder dry, the fire danger risk got stuck on extreme.

Then, in the middle of the afternoon of 5 February, in Pigeon Valley 30km from Nelson, there were flames.

They spread, multiplied and jumped. Entire hillsides were engulfed, homes evacuated, stock threatened, and the fight to fully extinguish the fire lasted three weeks.

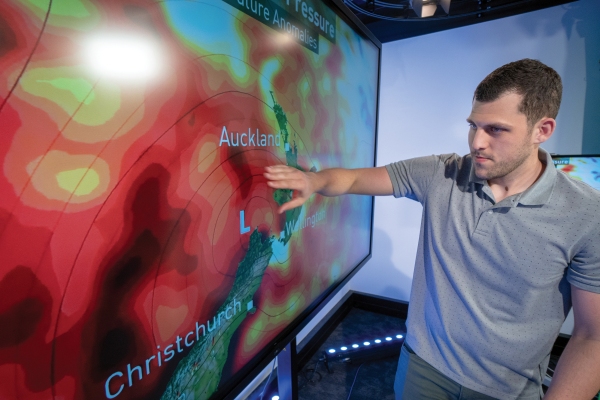

NIWA’s forecasters were pulled into the vortex, providing Fire and Emergency New Zealand’s (FENZ) incident management team with urgently needed high resolution weather and wind data.

By the time the fire was over 2434 hectares were burnt and it ranked as New Zealand’s largest forest fire in 60 years.

On the first day Richard and Jan watched the sky glowing orange above the ridge of flames until well past midnight. It was close enough to be terrifying, but not close enough to have to evacuate.

The Fentons had also witnessed the Port Hills fire of 2017, so when they shifted north they took some precautionary measures. They store 1000 litres of water in a pump on wheels for emergencies and harvest rain water stored in three tanks, adding up to another 75,000 litres. And in May they put in another two tanks that hold a further 30,000 litres.

A pond on their property is part way to completion – when full it will hold enough water for helicopters to dip their monsoon buckets into if it’s ever needed.

Richard and Jan are firm believers in being prepared. They have watched their corner of the world change in the last few years, and this year’s exceptionally harsh summer has focused their minds on how they can position themselves better for what’s coming.

New Zealand Summer of 2018/19

- 3rd Warmest on record

- 38.4 °C - Highest temperature recorded at Hanmer Forest, Canterbury, 31 January

- 105mm - Heaviest rainfall at Maungatautari, Waikato, 24 December

- >30,000 Lightning strikes recorded across the country on 14 December.

Winds of change

Scientists say it is not possible to ascribe one scorching summer to climate change, but they do know that extreme weather events are likely to become more frequent.

More wildfires are another possible consequence, although scientifically it is difficult to determine whether that is already happening here.

Fire & Emergency New Zealand run predictive models that help determine where a fire may occur over a certain period of time based on the conditions, and it expects fire danger seasons to be longer in the future. This year in Nelson the danger season doubled.

NIWA climate scientists have compiled several reports on regional climate predictions for councils around the country. These reports help communities adapt to the effects of a changing climate, which is likely to include temperature increases, more floods, storms, cyclones, droughts and landslips.

For Tasman, NIWA predicts a 5 percent increase in the frequency of droughts by 2050 and 10 percent by 2090. The risk of forest fires is also increasing, with scientists predicting a 71 percent increase in the fire danger season by the 2040s, under a mid-range warming scenario.

The Tasman district received under one-third of it’s normal rainfall over summer. Civil Defence and drought emergencies, with severe water restrictions, were declared. [Photo: Jim Tannock]

Fever in the ocean

Driving from Upper Moutere to Nelson is a scenic delight and from vantage points in the hills you can stop and look across the picturesque landscape to the Tasman Sea.

It’s useful to think about the ocean when putting the pieces of climate change together. Most of the heat generated by global warming – caused by pumping carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere – ends up in the ocean.

For the past two years parts of the Tasman Sea have experienced a marine heatwave, sometimes described as an ocean fever. Marine heatwaves occur when sea surface temperatures are extremely warm for a prolonged period of time. They can extend for thousands of kilometres (see Our changing oceans).

Marine heatwaves influence air temperatures and rainfall patterns. NIWA meteorologist Ben Noll says weather systems travelling over the sea pick up more water vapour when the sea surface temperatures are warmer. That means that ex-tropical cyclones heading towards New Zealand may not weaken as much as they normally would and retain their tropical integrity for longer.

Ex-tropical cyclones Gita and Fehi, which wreaked havoc on the West Coast and Nelson region last year, are good examples – they still had some tropical characteristics when they hit land.

New Zealand experienced its hottest summer on record over 2017/18, as well as a record marine heatwave, which spread the width of the Tasman.

Noll says the Tasman’s “ocean fever” was a striking feature on a regional and global climate scale.

This summer, while not the record breaker of the previous year, was also dominated by a marine heatwave.

Death by a thousand cuts

Agriculture Minister Damien O’Connor declared a medium-scale adverse event in Tasman on 8 February, unlocking funding for Rural Support Trusts to help in the recovery of farming and horticultural businesses.

Nelson MP Nick Smith said he thought the drought in 2001 was as bad as it could get ... until this one.

That was a sentiment echoed by Tasman District Council hydrologist Joseph Thomas, a council veteran.

“Droughts are very insidious, it’s death by a thousand cuts. You can see the grass shrivelling, the stock struggling, the plants wilting. It’s not like a storm or a flood which is gone in a day or two and then you get back on your feet.

“I have never seen some of the streams go dry in 30 years of being here but this year I did. We had to make some big calls. It is never easy recommending extreme water restrictions. People would come to a drought meeting and be in tears; their voices breaking. You could see how stressed they were.”

Growers were forced to choose which crops to save, farmers destocked, and cows were dried off early, but Thomas says there were a lot of people who were totally unprepared. “Many didn’t have a plan and would ask ‘What do I tell my workers?’. I had to say I don’t know.”

The final cost of the Tasman drought is still unclear, but some estimates go as high as $100 million. It’s not just one bad season, it’s the length of time it takes to recover what was there before it stopped raining. As well as lost crops and unproductive pasture to account for, there are job losses such as those caused after the fires shut down forestry operations.

Then there’s the impending changes to water plans needed in some of the Tasman catchments.

“It’s not just about everything that’s happening in the environment though,” says Thomas. “It’s also about community resilience and how much people can withstand.”

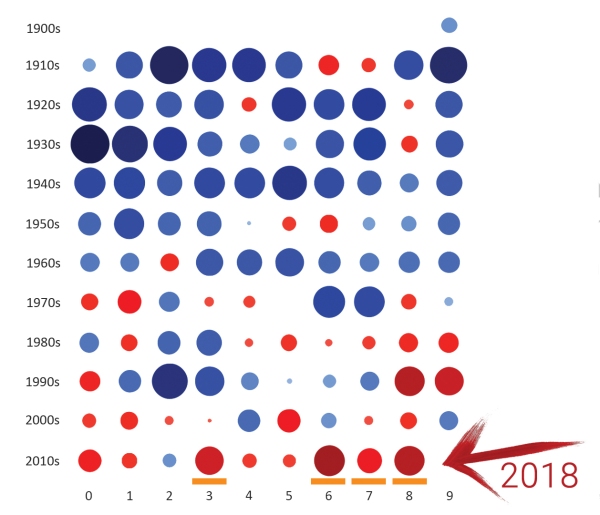

Four of the last six years have been amongst New Zealand’s warmest on record

Dot size and colour are based on temperature anomalies from NIWA’s 7 station series and are relative to the 1981–2010 average. [Photo: Nava Fedaeff, NIWA]

What next?

The first solid rain for Tasman came on 7 March – it was a relief of course, but not enough to reverse the damage across the district.

Jan Fenton kept a list of the things that changed over summer. It includes the tui that lived in a tree beside the house and then disappeared. Also on the list are missing kererū, a falcon, bees and dead trees – natives, redwoods, a silver birch and an old man pine more than 100 years old.

In early April the grass on the Fentons’ paddocks seems, if not lush, then plentiful. It’s an optical illusion. The ground is scarred with deep cracks every few metres and the grass is really tufts of spindly tendrils and little substance.

It’s winter now, and Jan has stopped looking at the weather forecast “50 times a day”. Soil moisture levels are mostly back to normal, and water restrictions have eased.

But the sea surface temperature is still warmer than normal, temperatures are above average and the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to rise.

GLOBAL

“The physical signs and socio-economic impacts of climate change are accelerating as record greenhouse gas concentrations drive global temperatures towards increasingly dangerous levels.”

State of the Climate in 2018 – World Meteorological Organization

Key points

- nine of the world’s 10 warmest years have occurred since 2005

- 62 million people affected by extreme weather and climate related events in 2018

- More than two million people directly displaced due to weather and climate events

- Record low Arctic sea ice cover registered for January and February

- Warming seas set new heat records for upper 700m and upper 2000m ocean zones

NEW ZEALAND

“We can be sure nearly all aspects of life in New Zealand will be affected by climate change.”

Environment Aotearoa 2019 – Ministry for the Environment

Key points

- four of the past six years have been among NZ’s warmest on record

- Southern Alps glaciers lost 25% of their volume between 1997 and 2018

- localised sea surface temperatures up to 3°C or more above normal recorded over the past two summers

- sea levels rose by 14–22cm between 1916 and 2016

- ocean acidity has increased 7% between 1998 and 2016