A giant squid and several glow-in-the-dark sharks were surprise finds for NIWA scientists last month on the Chatham Rise during a voyage to survey hoki, New Zealand’s most valuable commercial fish species.

But other denizens of the deep east of Canterbury kept NIWA scientists aboard research vessel Tangaroa on their toes.

At 7.34am on January 21 a trawl net was pulled from a depth of 442m. NIWA scientists were surprised to spot huge tentacles among the fish caught in the net.

Voyage leader and NIWA fisheries scientist Darren Stevens was on watch at the time and says it took six staff to lift the squid, weighing about 110kg, onto a tarpaulin. While the squid was more than 4m long, Mr Stevens described it as “probably on the smallish side”.

He says the ship was abuzz with news of the squid with sleeping scientists roused to take photographs.

"We knew there would be staff who wouldn’t be happy if we hadn't woken them for a giant squid.”

The squid was examined and dissected by Auckland University of Technology squid researcher Ryan Howard who was onboard to study the eyes of deepsea squid. Because there are several fully intact giant squid specimens on mainland New Zealand, the crew decided to take nearly 50kg of samples of the scientifically valuable bits including the eyes, head, stomach and reproductive organs.

“We managed to get an 110kg animal down to two 25kg boxes in terms of what was actually kept,” Mr Stevens says.

“We took the stomach because virtually nothing is known about a giant squid’s diet because every time people seem to catch one, there's very rarely anything in their stomachs.”

Mr Stevens says the eyes will be used for research and may shed light on the secret lives of giant squid.

“Getting two giant squid eyes is apparently enough for a scientific paper. They're really rare, and you need a fresh one. So it was a really unique set of circumstances to get two fresh eyes.”

The life cycle of giant squid is another mystery. The statolith—a tiny bone structure in the head—will be used to estimate the age of the squid.

“Currently there's no good way to age a giant squid. It's thought they live for more than one year that's for sure, maybe they live for three or four, but no one really knows.”

NIWA researchers catch a giant squid about once a decade. While giant squid are a global species, Mr Stevens says New Zealand seems to be something of a hotspot for catching them.

“New Zealand is kind of the giant squid capital of the world—anywhere else a giant squid is caught in a net would be a massive deal. But there’s been a few caught off New Zealand.

“It’s only the second one I’ve ever seen. I’ve been on about 40 trips on Tangaroa, and most surveys are about a month, and I’ve only ever seen two. That’s pretty rare.”

Glow-in-the-dark sharks

While the giant squid was an unplanned discovery, a visiting Belgian scientist on the voyage had every intention of finding glow-in-the-dark sharks.

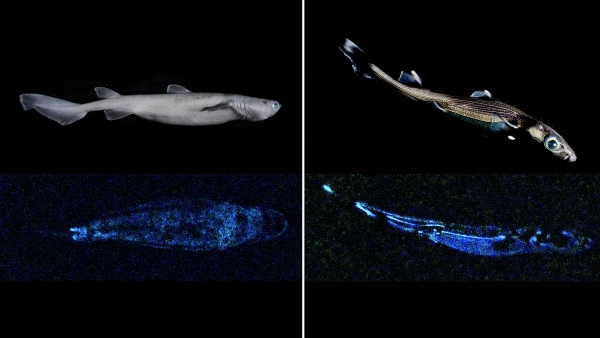

Dr Jérôme Mallefet of UCLouvain, a French-speaking university in Belgium, is the world’s leading expert on bioluminescent sharks. Bioluminescence is the emission of visible light by a living organism.

Dr Mallefet says that 62 out of 540, or 11% of all known shark species, can produce bioluminescent light. Most are small species that live in near-total darkness at depths of more than 200m.

Sharks, and other bioluminescent marine creatures, produce light for a few main reasons—predation, avoiding predation or for mating and schooling.

The Belgian scientist set up a dark lab aboard R.V. Tangaroa to photograph the sharks. The room was completely blacked out to mimic the darkness of the deep-water ocean and Dr Mallefet photographed the sharks using a specialised camera.

Before Dr Mallefet’s experiment no one had recorded bioluminescent sharks producing light in New Zealand waters.

“I was so happy. I was dreaming to get pictures of bioluminescent sharks [on the voyage] and I got them,” he says.

Dr Mallefet managed to photograph three species of bioluminescent sharks—the southern lantern shark, lucifer dogfish, and seal shark.

The sharks, like most bioluminescent species, produced blue light, a colour that travels well in the deep ocean.

Chatham Rise trawl surveys have been carried out by NIWA since 1992 and provide information that enables New Zealand to sustainably manage fisheries for hoki, hake, ling, and associated deepwater species. NIWA’s trawl survey research is funded by Fisheries New Zealand.

Related information:

More Coasts & Oceans news