PDF of this article (689 KB)

Lorna Pelly Gavin Fisher

A comparison between some renewable energy options for New Zealand and Scotland shows up some interesting similarities and differences.

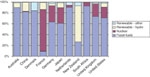

The energy crisis in New Zealand in early winter 2003 demonstrated the danger of committing the majority of the national energy production to one resource, particularly one that can be affected by the climate. Having 70% of electricity produced from hydro-power makes New Zealand one of the leading countries in the developed world in renewable energy generation (see graph). However, one dry summer later, and the disadvantages of this are clear.

The immediate response to the crisis was to reduce energy use – that is, improve energy efficiency – encouraged by a major Government marketing campaign. Looking further ahead however, with a population that is steadily increasing and the Maui offshore gas field steadily decreasing, there is a clear need to get some stability into the energy market. The option of diversification of resources, particularly using renewable forms of energy such as wind and waves, provides a theoretically sound solution but in reality this has not happened. Why not?

We compared the situation for the future of some new renewable energy resources – wind, waves and tide – in New Zealand with that in Scotland to see if the same barriers were present. The intention was to determine if there were any particular economic, political, environmental or social problems that could be identified as restricting development, and if these appeared to be occurring internationally. Our main findings are outlined below.

Mixed-source energy

The most obvious comparison apparent from this study was the extremely high resource potential in both countries, but far more projects have come on stream in Scotland. In both countries there is a need for further energy resource development with demand increasing and big question marks hanging over the future of certain major resources.

In Scotland, one of the major growth obstacles came from the national grid. Exceptional wind, wave and tidal sites are all available around the west coast of Scotland and north into the islands. However, the demand is in the south and the grid was built to take power up to the north; it does not work well in reverse.

This geographical discrepancy may not be such a problem in New Zealand, but highlights the problems that the grid can cause. The construction of the national grid is biased towards large-scale fossil fuel stations that can be flexible in location; it does not cater well for smaller generators in awkward sites. Overcoming this will immediately add to the cost of possible developments, often making them appear uneconomic.

This is not to say renewable energy cannot be successful, but it is apparent that it is only effective as part of a mixed-source system. A community relying on one wind farm would suffer many days without power, but these peaks and troughs of power could be evened out by the storage ability of units such as hydro lakes. Hence, a well-balanced grid, rather than a grid dominated by large units, is crucial to the success of renewables.

Flexible energy market

The UK has flexibility in its energy market and would have many options if an energy crisis seemed imminent. It can purchase electricity by cable from France and natural gas can be piped in from Europe. There are some large oil and coal-fired stations that can be stoked up again and emergency gas-turbine stations that can be fired up within minutes. All these options are expensive, but it seems unlikely that power cuts would ever be a threat.

New Zealand does not have this “option comfort” and therefore does need to review the balance of the energy market. Whilst new renewable energy systems are far from ready to fill the gap of the Maui gas field, they could bring much-needed stability to the market through resource diversification.

Teachers: this article can be used for NCEA Achievement Standards in Geography (2.3, 3.1, 3.6, 3.7) and Science (3.2). See other curriculum connections at www.niwa.co.nz/pubs/wa/resources

Lorna Pelly and Gavin Fisher are based at NIWA in Auckland.

Renewable energy research at NIWA

NIWA researchers are actively investigating renewable energy development in New Zealand in several research programmes.

In wind energy, NIWA has been the primary supplier of detailed wind resource measurements and modelling for many years, and has been involved in most wind farm developments. A new Wind Energy Atlas for New Zealand will be available in June 2003. The information supplied is used not only for determining the viability of wind power at any site in the country, but also for optimising the designs of turbines for maximum output at minimum cost.

Similarly, in solar energy NIWA is an important provider of resource information. New work is currently underway to take better account of the effects of cloudiness at particular sites, and to define UV effects throughout the country.

We also have research programmes in the exciting new energy sources of wave and tide power. New Zealand has considerable wave and tide resources, even though they are perhaps not yet commercially viable.

In the longer term, we are entering new programmes examining the prospect for hydrogen energy use in NZ, particularly in the transport sector. In collaboration with others, we are assessing the infrastructure issues, environmental effects, and barriers to implementation. As an energy carrier, hydrogen has the potential to make energy use very clean, and ultimately perhaps have NZ self-sufficient in most of its energy needs.

Finally, NIWA has recently begun a new programme examining the electricity needs of remote rural communities and, in particular, assessing the applicability of various renewable technologies to meet the needs of these communities. Prototype investigations are currently underway in Northland. (See page 4 in this issue of Water & Atmosphere.)

All of these are supplemented by our fundamental research in climate change, and the effects this might have on both the generation of renewable energy and on the demands from consumers.

For more information, contact: Gavin Fisher Private Bag 109695 Auckland Phone +64 9 375 2050 Fax +64 9 375 2051 g.fisher@niwa.co.nz.

Comparison of factors affecting alternative renewable energy development in Scotland and New Zealand.

| Scotland | New Zealand |

|---|---|

| High resource potential Wind sites of 10 m/s+ Wave sites with 66–76 kW/m Tidal currents of 4.5 m/s | High resource potential Wind sites of 10 m/s+ Wave sites with 30–40 kW/m Tidal currents of 1 m/s |

| Best sites in difficult locations In Scotland the best resource sites (mostly north coastal and offshore) are far away from the high demand (England). The grid restrictions between these areas have hindered development. | Sites in good locations There are good wind sites near the cities of Christchurch and Wellington. Potential wave and tide sites are also near high-demand areas. |

| Current developments low in number 81 wind farms generating 1.47 TWh 2 wave generators making 2.5 MW (2 more awaiting installation) 1 tidal generator of 300 kW | Current developments very low in number 3 wind farms making 35 MW (1 awaiting installation) |

| Further need for energy Increasing electricity demand (8% in last 5 years). | Further need for energy Increasing electricity demand (12% in last 5 years). |

| Privatised and regulated electricity market Regulated market, with price caps to ensure stability. | Self-regulating electricity market Lack of regulation can allow irrational connection costs. |

| Electricity generation based on gas, oil, coal and nuclear | Electricity generation based on hydro and gas |

| Potential loss of major energy source Nuclear industry (26% of market) future in question. | Potential loss of major energy source Gas industry (17% of market) future in decline. |

| Technical costs for equipment and construction of renewable energy systems still expensive With most manufacturing taking place in Europe, this is becoming less of a problem. | Technical costs for equipment and construction of renewable energy systems still expensive There is one wind turbine factory in New Zealand. |

| Kyoto ratified | Kyoto ratified |

| Government grants established Grant systems have been running for 10 years. | Government grants just introduced NEECS was launched late 2002. |

| Complex planning system Land acquisition has been a problem in Scotland, mainly due to conservation restrictions and public opposition. Local councils are now being encouraged to involve the value of such developments into their Local Plans. | All inclusive planning system In New Zealand, the Resource Management Act encompasses all planning and is an effects-based system that does not give value to renewable energy. |

| Degree of public opposition evident | Degree of public opposition evident |