At one end of NIWA’s Wellington campus sits a library. In that library are shelves - you can check things out, look at them and return them. But where there would normally be books, there are instead thousands and thousands and thousands of jars. And in each of these jars is a creature, preserved for eternity and mostly found in the sea around New Zealand.

Together they make up the NIWA Invertebrate Collection (NIC), a treasure trove of specimens for scientific study, and a nationally significant resource that is continually adding to our knowledge of what makes up New Zealand’s vast marine realm.

The Invertebrate Collection, housed at Greta Point in Wellington, comprises about 300,000 jars or specimens but only about 100,000 are officially registered. With new specimens being discovered all the time, there is a lot of work to do.

Collection manager

Marine biologist Sadie Mills is the collection manager – the perfect role for someone who combines a love of discovery with the satisfaction that comes from the order and strict organisation applied to the collection.

“I like to learn and I have a passion to know what things are. I’m also a list maker and I like to see things organised – you need to be into that to enjoy working with the collection.”

Where it all began

The NIWA Invertebrate Collection was started in the 1950s, as part of the now defunct New Zealand Oceanographic Institute, but it wasn’t until 2004 that the current specimen database was established improving access to the data that comes with the specimens. The variety of specimens is mind-boggling with the collection including enormous corals, delicate sponges, sharp-clawed crustaceans, pretty anemones, amphipods, miniscule organisms invisible to the naked eye and even a colossal squid beak.

The beak was found in the stomach of an Antarctic toothfish – another illustration of how the collection supports the work of scientists figuring out what fish feed on and where they sit in the food web.

Part of its value lies in having collected a good time series of samples over the last 60 years enabling comparisons to be made to determine change, or how processes like ocean acidification are affecting some of the species.

A collection of extraordinary biodiversity

But what makes the collection so extraordinary is the biodiversity of the specimens. The ocean surrounding New Zealand contains a range of habitats for marine organisms to thrive including shallow rocky reefs, deep canyons and trenches, hydrothermal vents, seamounts and abyssal plains.

The vast range of fauna in these habitats is a huge drawcard for scientists from all over the world who visit the collection to research their area of interest while adding to the biological inventory of the ocean around New Zealand.

New specimens arrive regularly to be stored in the low-temperature environment of the collection room. They are mostly gathered on scientific voyages or from scientific observers on fishing vessels but, says Mills, you can find new species just by going to the beach and examining a handful of sand.

“We are also still finding big things. In 2007, an anemone-like creature was discovered on the Chatham Rise and was named after NIWA.”

Behind the name

Taxonomists – scientific experts who describe and classify new species and subspecies – are called on to identify the samples which is a rigorous process that begins by giving a collection jar a unique number.

While basic identification including information on where it was found, the size, sex and weight and how it is preserved is recorded by collection staff, formal descriptions are completed by the taxonomists. A tissue sample is usually also taken to analyse genetic makeup to see how it fits within an evolutionary tree.

Mills is a taxonomic expert for brittle stars, of which there are about 200 species around New Zealand. She has described one species and is about to start work on another.

It’s a sideline to managing the collection but she plays an important role in providing baseline information for scientific research.

“It’s important to know what something is, so you can learn how it can be managed or looked after.

“If you don’t know what something is called you can’t know how it lives or how it fits into the food chain. You need to know what you’re dealing with before you can start making decisions about it.”

One example is king crabs – recent scientific study based on samples in the Invertebrate Collection has found that many more species existed than originally thought, some of which are common and some of which are extremely rare. Without that knowledge, it is possible that a species could cease to exist.

That is why the Invertebrate Collection houses a Type Room containing the most precious specimens and the ones that are used as the definitive reference point for a species. The dry collection, comprising most of the dry corals and sponges, is kept in a temperature-controlled room while the other specimens in the wet collection are preserved in alcohol and formalin.

In addition, the collection is also home to the Marine Invasive Taxonomic collection, which is a reference point to identify marine biosecurity risks to New Zealand.

Waiting to be discovered

The rate that new species are found is showing no sign of slowing down and it is estimated there are at least three times as many species that remain undiscovered as there are in the collection.

“There are new things waiting to be discovered right on our doorstep,” says Mills.

“What you see, you assume has a name but sometimes it doesn’t. There is just so much material and it is important that we take whatever small steps we can to look after the incredible diversity in the oceans.”

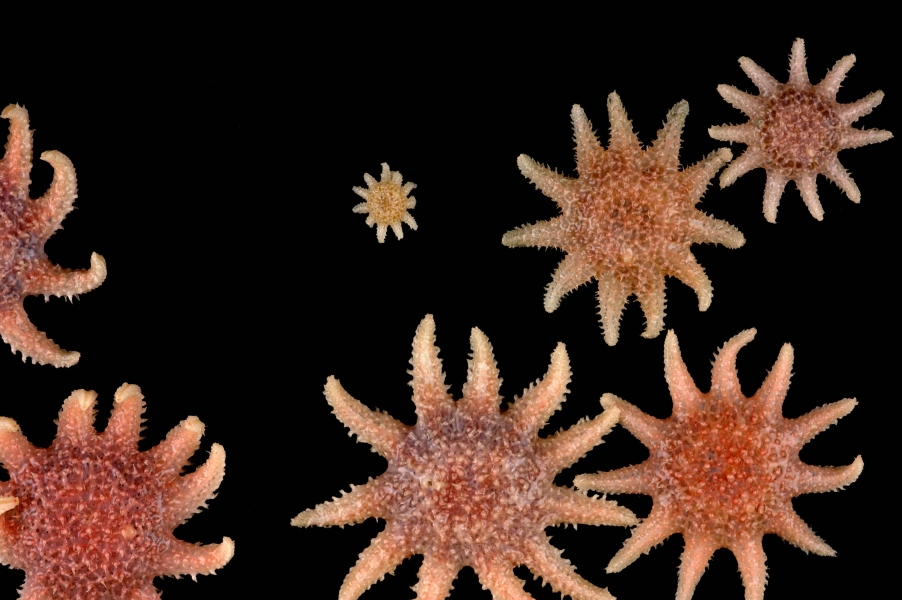

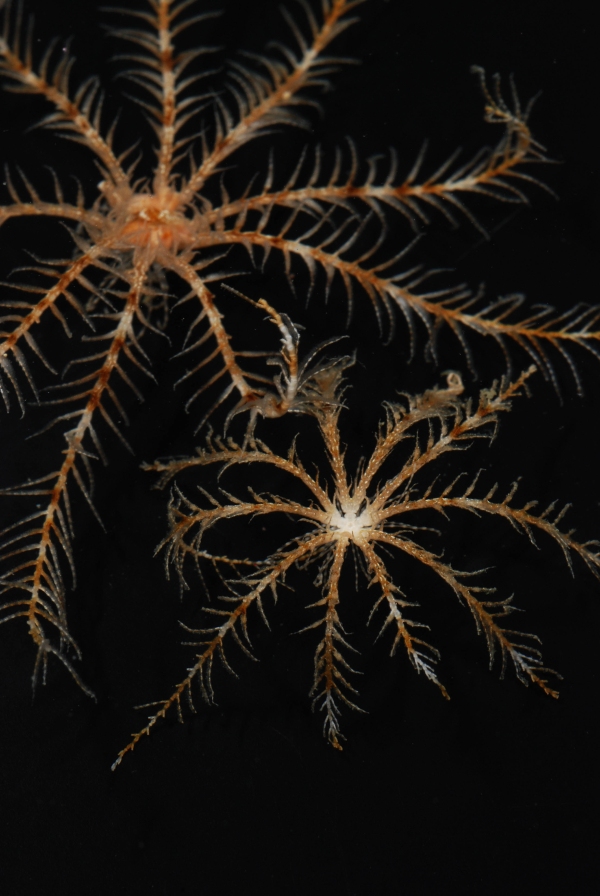

Images

The images (featured on the right side of this page) show examples of the diversity of specimens found in NIWA's National Invertebrate Collection. Click on the images to expand.

Furhter information

Read more about NIWA's Invertebrate Collection

Read NIWA's Invertebrate Collection's Critter of the Week blog series