In 1872 the HMS Challenger left Portsmouth in the UK on a four-year circumnavigation of the globe to explore the deepsea.

It was a scientific voyage of discovery that has since been recognised as the origin of deepsea science and modern oceanography. Such was its significance that scientists still examine specimens gathered on that trip, write papers referencing Challenger findings, and use sampling equipment that would not have been unfamiliar to their 19th Century counterparts.

The Challenger spent several weeks in New Zealand in 1874 – the crew and scientists unimpressed by the wintry weather, particularly around Wellington, but able to collect a large amount of scientific information and undertake a variety of measurements in our waters.

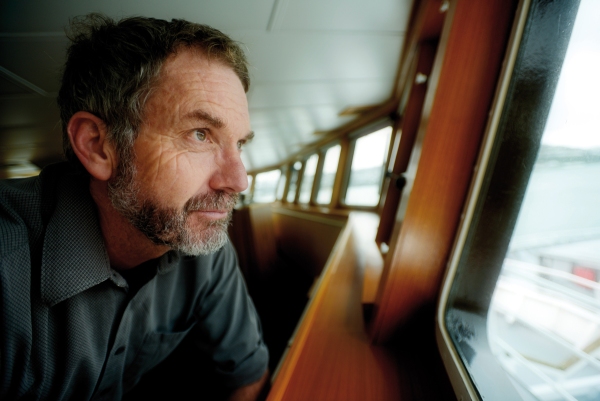

Almost 150 years later scientists, says NIWA’s Dr Malcolm Clark, are still exploring.

“In the deepsea, we don’t have a good understanding of how the system functions – we’re still going out there and finding new things and describing basic structure.”

That is why a group of deepsea researchers from around the world, including Dr Clark, have come together to outline what research needs to be done below 200m to better understand the human impact and changing vulnerability of these ecosystems.

They have been prompted into action by the United Nations General Assembly proclaiming the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development which begins on January 1. The roadmap for this decade calls for research to advance understanding to achieve four objectives:

- To increase capacity to use knowledge of the ocean

- To identify and generate ocean data

- To build comprehensive understanding of the ocean and its governance systems

- To increase the use of ocean knowledge

The group has recently published two papers responding to the UN call and proposing research that needs to be done and how the deepsea research community can achieve that research while using the decade to improve co-operation and collaboration internationally.

Dr Clark says the world’s oceans support the largest ecosystem on the planet covering about 60 per cent of the Earth’s surface, but with so much of it out of sight and out of mind most of us don’t realise how important they are to the functioning of the planet.

“We know the oceans are being affected by climate change. We are measuring altering conditions in the environment, and modelling indicates potentially significant changes this century.” Impacts from human activities such as fishing are well known , but there are also now more and more signs of human footprints in the deep-sea, including plastics and pesticide chemicals being found in some of the deepest parts of the ocean.

“We are seeing more human impact because the deep sea is a much more vulnerable system than shallow inshore seas. It’s not as dynamic, its biological communities are adapted to lower levels of natural variation in the environment that you get inshore.

“The deepsea is maybe a bit like travelling down a country road; it’s slower and more relaxed than a city motorway. The deep environment is dark, cold and productivity is less – things happen on much longer time scales.”

Dr Clark has studied deep-sea ecosystems for several decades and headed the Census of Marine Life on Seamounts, a major six-year international research programme. He has been on more than 80 scientific voyages and leads a number of NIWA’s research projects investigating effects of human activities on deepsea habitats and ways to improve the management of environmental impacts.

He believes the concept of a decade of ocean science will enable scientists to progress understanding of ocean processes which will “hopefully mean better management of our ocean resources-improve ways in which we balance exploitation and conservation”.

“The key in the first instance is to work better together as an international science community, recognising that the deep sea is not restricted to one country or region and we learn so much more by looking at larger scales and processes than we are generally able to with objectives driven by any single country. This initiative will give us a chance to align some national projects under a global umbrella.”

While it’s early days, Dr Clark has signed up his research funded by the Ministry for Primary Industries into Chatham Rise seamounts and how they recover after bottom trawling, to be part of the programme.

“Although this work is driven by New Zealand’s science needs, if we put a whole lot of studies together from around the world that have something in common and use comparable data, then we can extend our analyses way beyond the national horizon.”

Dr Clark says the Southwest Pacific is one of the lesser explored areas in the world despite New Zealand’s position geographically.

“We’re effectively a maritime nation, and have one of the world’s largest Exclusive Economic Zones, which means as a country we take marine research seriously. Because we’re on a tectonic plate boundary our deepsea topography is incredibly diverse with offshore continental rises, seamounts, trenches, and canyons."

“But this diversity means we struggle to understand the complicated ways in which our marine environment operates, let alone interactions beyond our shores to the south west Pacific or the Southern Ocean. We’re geographically at the crossroads of a whole lot of ocean complexity which is scientifically very exciting but also a huge challenge.”

Meanwhile, the 150th anniversary of the Challenger voyage occurs during the decade which Dr Clark and his fellow researchers hope will also help to shine a light deep down in the ocean by adhering to the project’s motto: “The science we need for the ocean we want.”

Website: www.oceandecade.org

This story forms part of our 2020 Summer Series. Check out more stories from the series.