The remarkable long distance swimming abilities of penguins have impressed NIWA scientists who have tracked almost 100 birds over winter in the Southern Ocean.

Until now, no one knew where the sub-Antarctic rockhopper and Snares penguins went while they were at sea between April and October each year.

However, an ingenious tagging project, led by NIWA seabird ecologist Dr David Thompson, has found the penguins travelled more than 15,000km in six months.

“If they are constantly moving this averages out at about 100km a day but you also have to add on to that the distances covered vertically as the birds dive to capture food,” Dr Thompson said.

Rockhopper population declines

The tagging programme targeted rockhopper penguins at Campbell Island and Snares crested penguins, endemic to Snares Island. While the Snares penguin population is relatively stable, rockhoppers at Campbell Island have declined by at least 21 per cent since 1984 leaving just over 33,000 breeding pairs on the island. The island was once the world’s largest breeding colony of rockhoppers, but between 1942 and 1984 the population dropped by about 94 per cent.

It is not known what has caused such a sharp decrease but one theory is that changes in the penguins’ diet may be responsible.

Dr Thompson says they have an extreme lifestyle.

“They come to land to breed and when they finish that, go back out to sea where they feed up for a month. Then they come back to land to sit and moult their feathers. During that period they don’t eat at all,” he says.

“Having basically starved themselves they go back out to sea in poor condition. They’ve grown a whole new set of feathers so their plumage is fantastic but it’s quite demanding so they’re really scrawny.

“We think winter is pretty important and that there is almost certainly something going on in the ocean causing the population to decline.”

The first stage to solving that mystery was a tracking project to find out where the penguins go. But attaching a tracking tag to a penguin takes a lot of travel, lateral thinking and a fair amount of nimble footwork.

Firstly the tags had to be modified from fitting the long, skinny leg of an albatross to the short, stubby leg of a penguin. Then Dr Thompson and his team had to time their arrival on Campbell Island, 620km south of Stewart Island, with the end of the moulting season, just as the penguins were ready to leave for the winter. Then they had to clamber down rock faces and steep cliffs to reach them. Of the 90 penguins tagged for the project, about 80 returned the following spring when the tags were retrieved and data processing began.

Long distance winter travellers

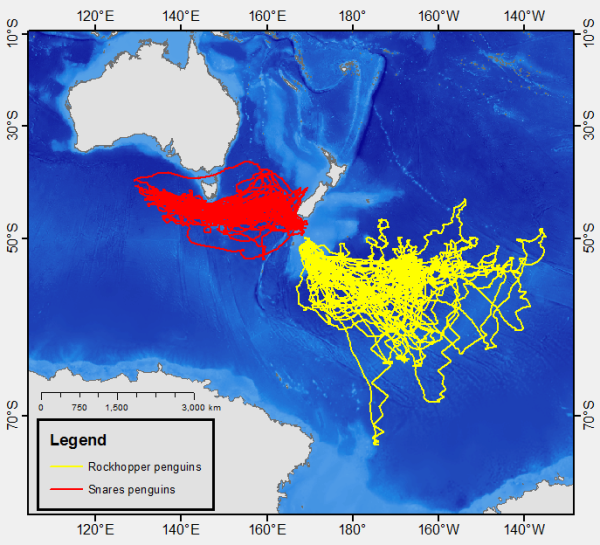

The picture that emerged was a revelation. The Snares penguin headed exclusively west towards Australia, while the rockhoppers went east and covered a wider section of the ocean. Several birds covered more than 15,000km over the winter. The tags were also able to determine when the penguins were stationary, indicating they had stopped to dive for food or rest.

Dr Thompson says this first tracking project has provided only a snapshot but says the work must begin somewhere.

“We don’t know what they’re feeding on when they’re away; we don’t know if the amount of food available was more or less comparable to five or 10 years ago so this is very preliminary.”

He has plans to repeat the project and include other species, such as the erect crested penguin of the Antipodes Islands.

“The extra species will give us more information on how they relate to each other when they go away. It may be that they use different space, or it may be that populations of different islands get together at sea.

“Research like this is important to better understand what’s important for penguins. It is possible that particular parts of the ocean may help them get through from one year to the next so we need to be able to identify those places”.

“Prior to this study we didn’t have a clue where rockhoppers went in the winter but the spaces they use in the ocean might be really important—not only for them but for scientists to better understand what is causing the population decline.”