The Quota Management System, which some say saved New Zealand fisheries, is 30 years old today. The system is founded on science that studies fish biology, abundance and distribution, and estimates how many can be caught and still keep the population healthy.

In April this year 40 fisheries ministers and officials from Pacific nations came to Wellington to learn about New Zealand’s catch-based fisheries management system.

They were here because New Zealand Prime Minister John Key offered the tour at last year’s Pacific Islands Forum leaders’ summit. The offer was part of a US$34 million fund provided by New Zealand for the region to set up a catch-based system.

Catch-based management means a limit is set on the volume of certain species caught. Commercial fishers are assigned a portion of that volume. The catch volume is set, and adjusted if required, so that the productivity of each species can be maximised. The secret to the success of the system is good science to help inform sustainable management. It is essential to accurately assess how many of the species exist, where they live and move, and how they reproduce and grow. Only then can you confidently set a catch volume that will allow the population to regenerate.

The Pacific leaders were here because New Zealand knows a thing or two about such systems. It manages the nation’s commercial wild fish catch of 130 different species, worth $1.3 billion in exports each year.

Cook Islands Prime Minister Henry Puna says the New Zealand system is one of the best in the world. He says adopting a similar quota management approach will ensure the sustainability of Pacific fisheries.

“We all share a common objective of making sure that fisheries in the Pacific are sustainable well into the future and we believe that the Quota Management System will deliver that for us.”

The visit to learn from New Zealand’s expertise illustrates the maturity of a system which turns 30 years old this year. The pearl anniversary is an opportunity to reflect on a decision in 1986 that effectively saved the industry. In fact, quota management has turned into a saleable advantage for fish exporters. In a world obsessed with sustainability, the fact that New Zealand fish catches come from guaranteed sustainable populations adds marketability and value.

Thirty years on, it’s hard to recall exactly how desperate the situation once was.

A former Ministry of Fisheries Deputy Chief Executive, Stan Crothers, describes the period as ‘the wild west’.

Like every other country in the 1980s, New Zealand had managed its fisheries using traditional input controls like size limits, gear restrictions, seasons and area closures. And, like many fisheries around the world, our inshore industry was overcapitalised. Too many boats were chasing too few fish.

“By the early 1980s, New Zealand fisheries managers found themselves in a very challenging situation,” according to Crothers.

“Deepwater fisheries had recently begun to be developed and we wanted to see that development continued in a way that was economically rational and sustainable. Our inshore fisheries, meanwhile, were on the verge of economic collapse.”

Measures such as moratoriums and controlled fisheries failed to work. Something more radical was needed. It was a huge challenge for government and industry to institute a management system that could effectively deal with both the offshore and inshore situations.

Crothers says the QMS was a product of its time, a period of huge government reform and change in New Zealand society. “Market economics was the flavour of the day, and the QMS incorporated a strong element of this by creating a market in commercial harvesting rights.”

A point of difference to other quota systems was the creation of Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs). These allocated defined tradable shares to fishers, allowing them to catch the fish when it was most economically viable for them. This reduced wasteful competition from a ‘race to fish’.

“The idea was that such a market would provide business certainty and encourage investment and efficiency in the fishing sector.”

In October 1986, after two years of consultation and planning, the Quota Management System was introduced with widespread industry support.

Initially the fishing industry had to endure lean times. To allow inshore fish populations to rebuild and support larger catches in the future, the initial catches were set very low – less than half the previous catch levels and some as low as 17 per cent. The Government offered compensation for the catch reductions. Yet, in many stocks, the reductions were not enough, forcing the balance of quota to be reduced without compensation.

The seafood industry is now a major champion of the QMS approach, and a constructive contributor to its regular tweaking. Tim Pankhurst, Chief Executive of Seafood New Zealand, says, in contrast to the ‘the boom and bust’ period before the QMS, fish stocks are now managed sustainably.

Pankhurst says the accuracy of science about fish is as vital to sustainable fishing as the Quota Management System itself.

“The science tells us that New Zealand’s fisheries are performing extremely well, with around 83 per cent of individual fish stocks above the level where sustainability would become a concern.”

Scientists from NIWA, and formerly the Ministry for Agriculture and Fisheries, have been involved from the start of the QMS. Over the period, they’ve taken great steps in improving the accuracy of its fish stock monitoring counts, and assessment of productivity levels.

Rosemary Hurst, NIWA’s Chief Scientist Fisheries, says one of the most significant advances in fisheries science in New Zealand over the 30 years has been the development of fishery-independent methods to monitor fish abundance.

“Long time-series of fisheries monitoring allows us to better understand natural and fishing-induced variations in abundance. We are increasingly confident about our estimates of fish abundance, and the impact that fishing has on fish stocks.

“For example, we’ve created 25-year-long time-series of trawl and acoustic surveys, using the NIWA research vessels Tangaroa and Kaharoa. A quarter of a century of these data enables provision of reliable abundance indices for stock assessment of key species, as well as environmental indices for secondary species caught on the surveys.”

Also essential to robust stock assessments is the collection of reliable fishery-dependent data. There are a number of data types available as inputs to the assessment models.

“One of these is the fine-scale commercial catch and catch-rate reporting for most of New Zealand’s fisheries that is now amongst the best in the world,” says Dr Hurst. For the key fisheries, we also have valuable time-series of catch sampling data (verified catch weights, fish size, sex, spawning conditions and age) collected by Ministry observers on offshore ‘deepwater’ vessels, since the late 1980s, and from landed catches for inshore species.

Model data inputs include all the available reliable data, including commercial catch rates, research abundance indices (from trawl, dredging, potting or acoustic surveys and tagging studies), population age or length structure, growth and age of maturation. For inshore species, recreational catch data may also be included.

Digital advances

Rosemary Hurst says scientists have a lot to be proud of in their contribution to New Zealand’s stock monitoring and assessment processes. Particularly noteworthy is development of state-of-the-art analytical software such as NIWA’s stock assessment model, CASAL. The NIWA-developed software package is an international standard in the assessment and management of fish stocks, including some of the world’s most prized species. It is being used by overseas agencies to assess Patagonian and Antarctic toothfish and broadbill swordfish fisheries.

NIWA fisheries scientist and CASAL development team leader Alistair Dunn says the software has become a universal language of fisheries science.

“There are lots of communication barriers in international communities, so this gives us a standard language to use on the topic.

“We have just built a new generalised population modelling package, CASAL2, to extend and replace CASAL, allowing us to model marine mammal and seabird populations as well. We are also starting to develop a suite of more complex spatial and ecosystem models that will underpin our science used to understand and manage marine ecosystems. In New Zealand, fisheries are typically managed to achieve a target spawning biomass (total mass of breeding fish) of around 40 per cent of its original size fishing. If the biomass level falls below 20 per cent, it’s regarded as overfished, and one below 10 per cent is considered collapsed and at risk of not recovering.

“NIWA’s population modelling tools allow us to evaluate the potential risks in order to maximise catches without damaging the stock population.” Using this science, the state of important fisheries like hoki and orange roughy have improved over the past 10 years, and are now well above target biomasses and support sustainable catches.

Rosemary Hurst points to an emerging need to be able to make stock and risk assessments even in ‘data poor’ situations. “Our science underpins the Marine Stewardship Council Certification for hoki, southern blue whiting, hake, ling and toothfish.”

How the quota system works

The aim is to conserve major fisheries stocks at sustainable levels and to improve the efficiency and profitability of the New Zealand fishing industry. This is done by managing fisheries at the level of Maximum Sustainable Yield. The principle of a Maximum Sustainable Yield is used to establish the level at which the sustainable catch is highest. Fish stocks are generally most productive at between about 30 per cent and 45 per cent of their unfished size, because a decrease in population reduces competition for food and results in a younger and faster-growing population.

Since 1986 the Ministry of Fisheries has gradually brought more commercial species under the management of the quota system. In 2014 the number of species reached 100, split into 638 regionally distinct stocks (Quota Management Areas).

Scientists and the industry work together to assess the population of each species and stock in the system. From this, the Ministry for Primary Industries makes recommendations to the Minister to set a Total Allowable Commercial Catch (TACC) for each species in each QMA. Individuals and companies are allocated the right to catch certain quantities of particular species, or ‘quotas’. Quotas can be leased, bought, sold or transferred.

In areas where significant non-commercial fishing exists (for example, recreational) this is taken into account and a portion of the total allowable catch is set aside before the TACC is calculated. In 1986, when the Quota Management System was brought in, quota was allocated to individuals and companies as Individual Transferable Quota (ITQ) on the basis of catch history. Each ITQ entitles its holder to a certain share of the yearly TACC for a particular fish species in a particular area. ITQ has economic value and can be traded or leased. Asset value of ITQ in 2015 was about $4 billion.

Treaty of Waitangi

About the same time as the fisheries were in stock crisis, Māori claimants were concerned that the Treaty of Waitangi guarantee of “full, exclusive and undisturbed possession… of their fisheries” had not been honoured. Both the Waitangi Tribunal and the Government agreed that their claims had merit and negotiated a full and final settlement of Māori claims to sea fisheries. They granted to Māori 10 per cent of Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs), 20 per cent of new species in the QMS, 50 per cent of Sealord Products Ltd, and a method of identifying traditional fishing areas and custom-based regulations.

It is estimated that Māori currently own about 50 per cent of the fishing quota.

A wealthier nation

A study by Statistics New Zealand (2009) revealed that the fisheries asset—the number of fish in the sea and their value—has increased.

The study demonstrated the long-term value of the QMS in what has happened to the original 26 species which started the system. Between 1996 and 2009, their asset value increased 18 per cent, even though their TACC declined by 40 per cent. The value of all commercial species in the QMS increased by almost 50 per cent between 1996 and 2009. The total asset value of New Zealand’s fisheries is currently over $4 billion.

The growth in scientific knowledge has supported new species to be added to the QMS, and their TACCs sustainably managed. This sustainable management has also enabled some key fisheries to obtain Marine Stewardship Certification, which also adds to export value.

In the past 30 years the QMS has proved its value. It would not have been possible without scientists knowing, with a great deal of confidence, how many fish were left in our sea.

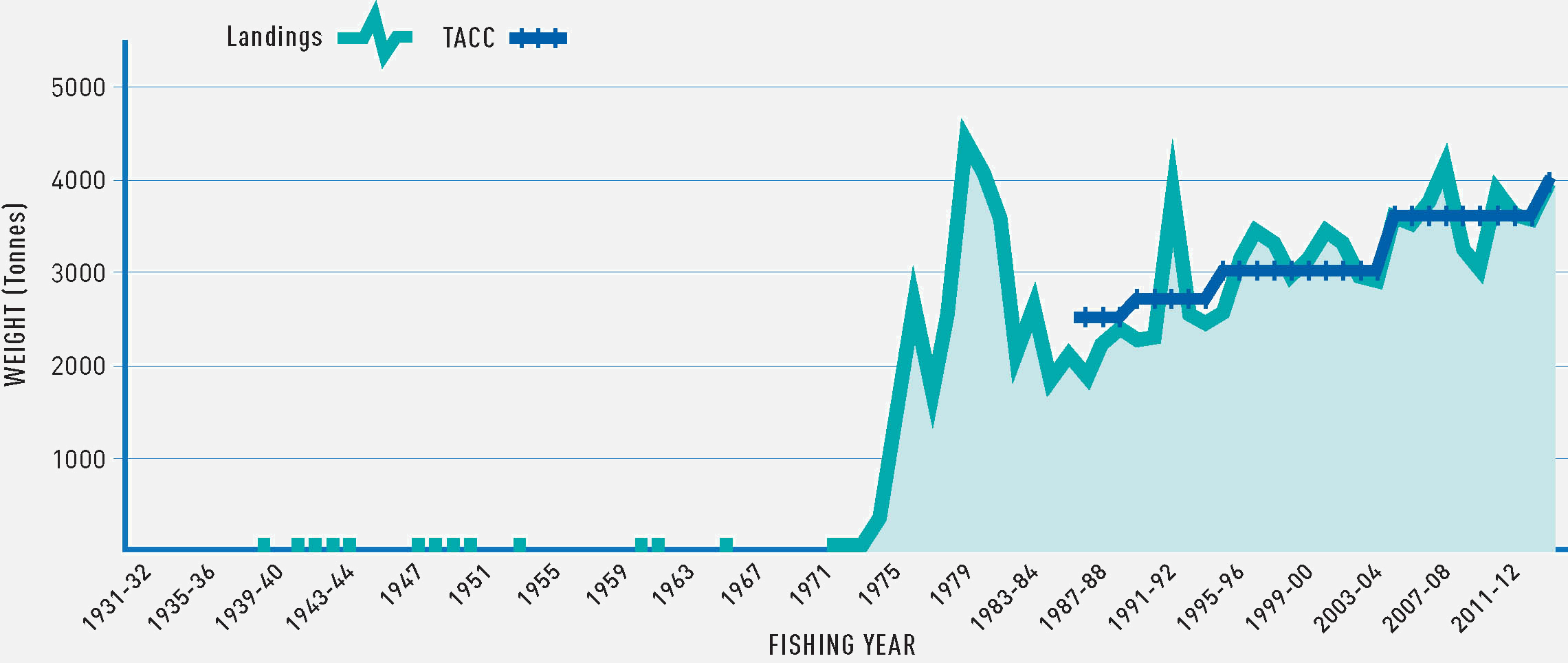

The story of lingLing is one of the ‘deepwater’ fish species that had a short time-series of catches prior to 1986. There was considerable uncertainty about its sustainable levels when TACCs were first established. Since then fisheries assessment has estimated the population using Tangaroa trawl surveys, research and commercial catch-at-age distributions, and commercial catch-per-unit-effort. The result has been a growing confidence to gradually increase the ling TACC over time. Continued monitoring is showing the increasing TACC to be sustainable.

|

Note: This feature originally appeared in Water & Atmosphere, June 2016