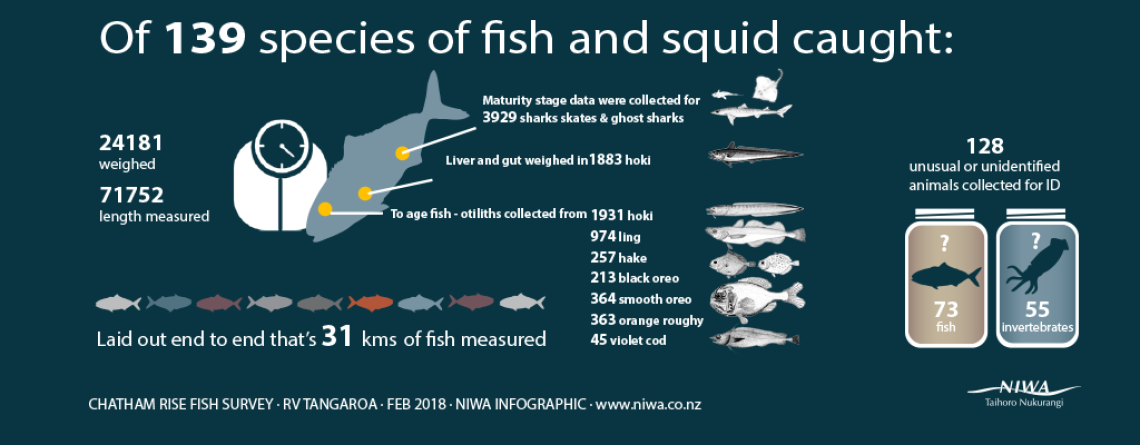

When NIWA fisheries scientist Richard O’Driscoll went to sea earlier this year, he and his team measured so many fish that laid end to end, they would have stretched for 31km.

That’s 71,752 fish to be exact – and a crucial part of NIWA’s annual assessment of New Zealand’s hoki stock. Conducted from NIWA’s flagship research vessel Tangaroa, one of the main aims of the month-long survey is to provide information that enables the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) to sustainably manage the hoki fishery.

“Results from this survey feed into a hoki population assessment, which supports an MPI consultation process before a decision on total allowable catch that is usually announced in late September, in time for the October 1 start to the fishing season,” Dr O’Driscoll says.

Hoki is a fish in demand. It is used by fast food chains in fish burgers, appears in supermarket freezers as fish fingers, crumbed or battered fillets, and can be bought fresh. Commercial fishing companies can catch up to 150,000 tons of hoki during the fishing season and it is an important export earner ($229M in 2017).

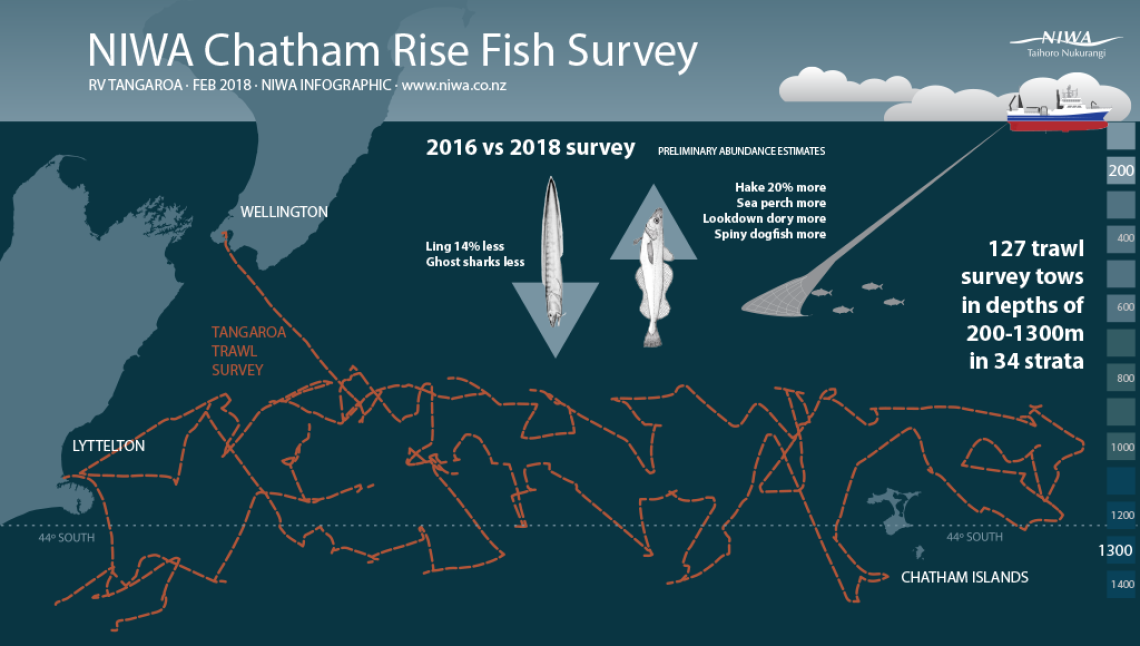

Ensuring the hoki fishery remains healthy and sustainable includes monitoring the abundance of juvenile fish. This is done during the biennial trawl survey carried out by NIWA on the Chatham Rise, which measures the abundance of juvenile fish from both New Zealand hoki stocks – one that spawns on the West Coast of the South Island, and one that spawns in Cook Strait.

“Juveniles of both those stocks end up together on the Chatham Rise, they get there when they are about a year old, stay all together until they’re about four. Doing the survey here allows us to assess the numbers of small hoki from both stocks when they’re in the same place.”

The hoki population has undergone some large fluctuations in the last few decades, due in part to some large annual changes in the numbers of juveniles. In the 2000s, the total allowable catch was drastically reduced from 250,000 to 90,000 tonnes following successive years of few younger fish appearing. Since then the quotas have gradually increased as the stock has grown and this year is set at 150,000 tonnes.

There are several additional pieces of scientific information that contribute to deciding the quota level. They include:

- Results of an acoustic survey in Cook Strait and another biennial trawl survey in the Sub-Antarctic, both conducted by NIWA

- Information from commercial fishing vessels and MPI fishery observers who measure fish at sea and collect otoliths (earbones) which are used to determine the age of fish.

- NIWA sampling of hoki in fish processing facilities

“All that information gets presented as the biological input to stock assessment, usually in late February.”

From there scientific modelling of all the available information is used to update the assessment of the stock, and a working group report is put together by MPI. The process also includes public consultation if changes are proposed.

The last step is a decision and announcement by the Fisheries Minister on the total allowable catch for the next fishing year.

“There is a direct link between what you go out and measure and the management action that ensures sustainability of the fishery – that’s one of the reasons I enjoy it,” Dr O’Driscoll says.

Highlights from this year’s hoki survey

- 127 successful trawl survey tows were completed at 34 different depths.

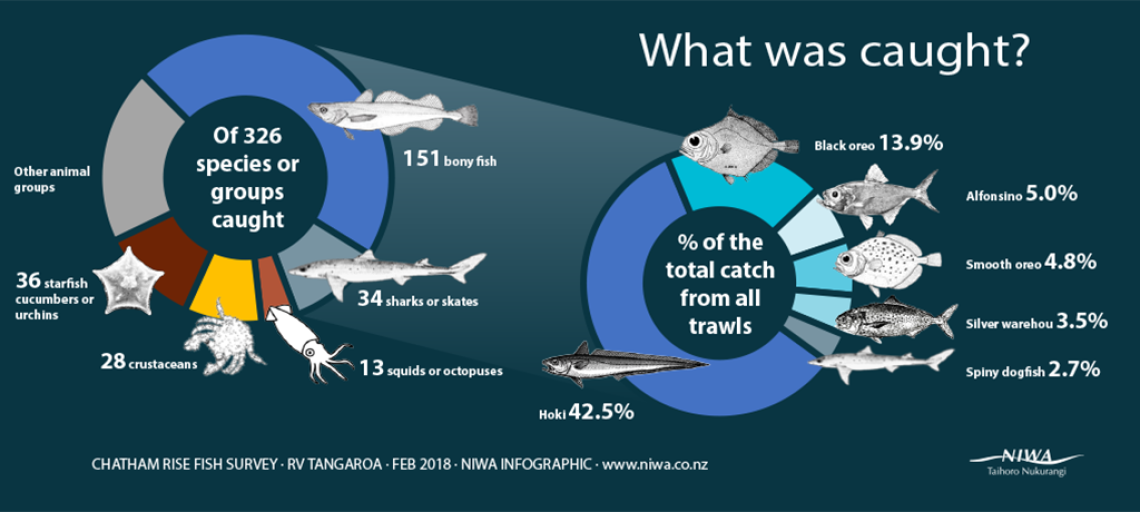

- The total catch of 159.8 t comprised: hoki 42.5%, black oreo 13.9%, alfonsino 5.0%, and smooth oreo 4.8%.

- 71,752 individual fish of 139 species were measured. If laid end-to-end these would stretch more than 31km.

- 334 kg of samples were frozen for further analysis ashore.

- The average surface temperature was 17.1o C: a couple of degrees warmer than usual. However the warm surface layer usually only extended to 50 m deep.

- More than 100GB of acoustic data were collected using the Tangaroa suite of multi-frequency echosounders.

- Abundance estimates for hoki suggest good recent recruitment from 2015 and 2016 year-classes.