Microplastics are being fed to snapper, New Zealand’s most popular recreational fish species, at NIWA’s aquaculture research facility near Whangarei in a bid to establish some baseline data about how fish are being affected.

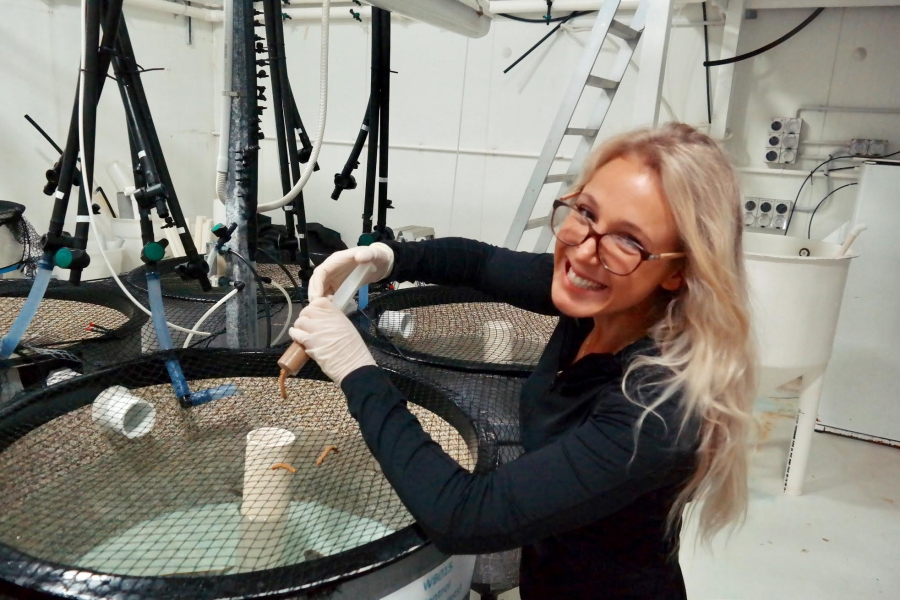

Auckland University masters student Veronica Rotman, under the supervision of NIWA fisheries scientist Dr Darren Parsons, is undertaking a two-part experiment to understand how one of the world’s most pervasive pollutants is affecting fish in New Zealand waters.

Ms Rotman says little research has been done in this area and she saw an opportunity to undertake some work that was relevant to New Zealand.

“It’s critical to find out what’s going on with plastic in our ecosystems—I want to see whether the plastic is egested, remains in the gut or migrates to other parts of the fish, including the flesh we eat.”

Using some coloured polystyrene—one of the ocean’s top five plastic polluters - and a blender to generate microplastics between 50 microns and 2mm in size, Ms Rotman then soaked some samples in the Waitemata Harbour for just over a month to mimic similar conditions fishes experience in the environment.

“Plastic acts a sponge for pollutants, soaking up harbour waste—industrial chemicals, pesticides, heavy metals and bacteria, so I wanted a relevant environmental treatment.”

The polystyrene is then fed in varying amounts to 160 juvenile snapper, New Zealand’s most popular recreational fish species, held in 20 aquaculture tanks at NIWA’s Northland Marine Research Centre at Bream Bay along with their regular diet.

After 10 weeks of treatment the snapper will be dissected to determine how much the fish have retained, any effects on growth or condition, whether it has done any damage to their gastrointestinal tract, and whether the microplastics translocated into the liver and muscular tissue.

“What I’m really interested in is the levels of toxicity caused by microplastics accumulating in the digestive tract. The snapper experiment should shed some light on whether microplastics can translocate into the flesh we eat and how exposure may impact their physiology, reproduction and fitness.”

The second part of the experiment will see the focus shift to hoki—New Zealand’s most commercially valuable finfish species. Hoki are a deep-sea fish and Ms Rotman will examine specimens from Cook Strait, the West Coast and the Chatham Rise to investigate any plastic incidence in the gut.

“It will be very interesting to see whether hoki are consuming microplastics and if there are any variations between the different sample locations due to proximity to human settlement and sources of pollution. “

This work will contribute to Ms Rotman’s Masters thesis and she is intending to submit a paper on the results to a scientific journal for publication.