Written by Dr Andrew Lorrey, NIWA Principal Scientist – Climate & Environment

On this page:

Download a shorter version of this lesson in PowerPoint or as a PDF or continue below to see the lesson in full.

Cold regions across Earth from the high mountains to the poles are the home of glaciers. Glaciers are beautiful to see and are a majestic, pristine part of our natural landscape. But what exactly is a glacier, and how do they work?

What is a glacier?

A glacier is a huge mass of ice that moves slowly over land. They are formed when lots of snow that builds up year after year in the same location turns into ice.

Over time, the snow at the bottom gets compressed (squashed together) by the weight of the new snow falling on top, forcing it to change into ice. This isn’t a quick process – it can take hundreds and even thousands of years for a glacier to grow. The snow changes to ice granules, an icy crystallised substance called firn and eventually ice as more and more air is pushed out.

Steps in the process of formation of glacial ice from snow, granules, and firn. Source: Steven Earle (2015) CC BY 4.0

Glaciers can start to grow in places where snowfall is preserved from year to year over long periods of time.

Glacier ice contains mostly water, air bubbles and small amounts of dust and debris. Glacier ice has a lower density than water, which is why icebergs from glaciers float in water!

Where are glaciers found and why?

Glaciers can be divided into two groups: alpine glaciers and continental ice sheets

Alpine glaciers

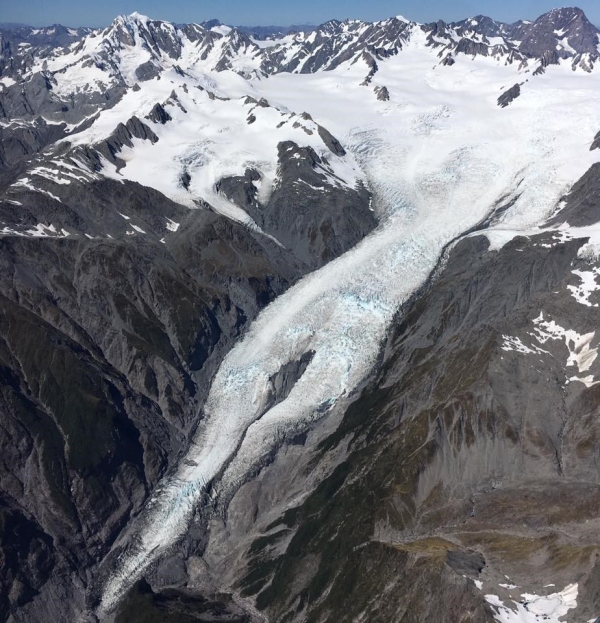

Alpine glaciers form on mountainsides and move down through valleys. In New Zealand, alpine glaciers form in and around the Southern Alps. Our highest volcanic peaks on the North Island also have small glaciers.

Glaciers form here because the mountain tops stick high up into sky where it is so cold the snow doesn’t melt and is able to turn into ice.

Continental ice sheets

Continental ice sheets form and spread out over large areas of land. Polar environments where continental ice sheets form, like Antarctica, are cold enough for glaciers to form because they are furthest away from the equator meaning they get less direct sunlight than any other places on Earth.

How do glaciers move?

A glacier may just look like a huge block of ice sitting still, but they are in fact moving. The weight of the ice, along with gravity, cause the glacier to move very slowly downhill, like a slow-flowing river.

The huge weight of the glacier causes ice at the bottom to change shape and begin to flow, moving the glacier along. Sometimes water running under the bottom of the glacier can help it to move along too.

Ice at the top of a glacier moves faster than ice at the bottom because there is less friction. The bottom of a glacier moves more slowly due to the friction between the ice and rocks it is lying on.

Most of the time a glacier moves very slowly but sometimes the amount of ice, and conditions at the base of the glacier, can cause it to flow quickly enough that we can see it moving with our own eyes.

Why do we study glaciers?

Glaciers are important indicators of climate change because they are very sensitive to changes in temperature and precipitation (rain and snow). They can tell us a lot about how the environment is changing and can help us explore what the impacts of changing temperatures are for times and places where we don’t have a lot of data. We can also study glaciers to find out what the climate was like in the past, hundreds and even thousands of years ago.

Glaciers are also important water resources for many parts of the world because they store immense amounts of freshwater. In some situations, water formed by the melting of snow and ice can be helpful to supplement our water supplies – particularly during years when we have strong seasonal droughts.

What are the tools scientists use to study glaciers?

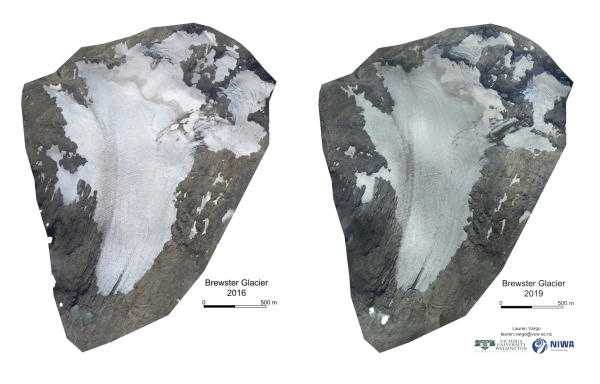

Scientists study glaciers by making regular observations from on the ground and in the air, then comparing these observations to past observations to see how a glacier is changing over time.

They use a wide range of equipment like weather stations, photographs, maps, radar equipment, and cameras to make these observations.

Below are some examples of the observations scientists make to study glaciers.

Snow markers

Scientists can put stakes into a glacier after the end of summer to see how much snow falls and melts during the following months.

Maps

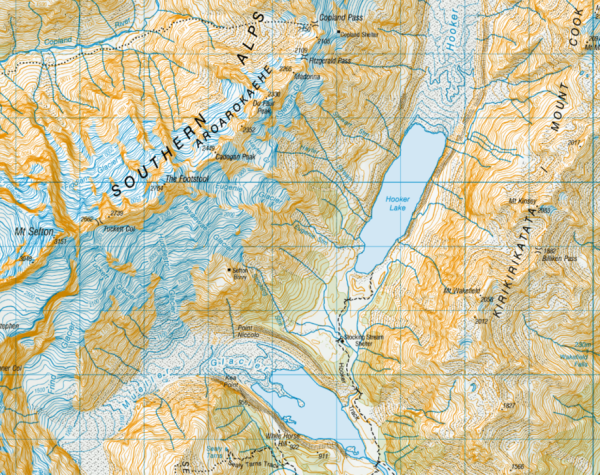

Historic maps and geographic information systems (GIS) let us make glacier inventories, where we can measure and count all the glaciers and how they are changing through time. The first NZ glacier inventory in 1978 counted 3144 individual glaciers!

Thermal images

Thermal images show how the temperature of the air is affecting a glacier. In the summer, some glaciers can reach surface temperatures between

What is the impact of climate change on glaciers?

Climate change is causing the Earth to get warmer and these warming temperatures are causing glaciers to melt faster than they can build up snow and continue to grow. If temperatures continue to rise, glaciers will continue to melt, and some could disappear completely. The water from the melting glaciers flows into the ocean and contributes to sea-level rise.

We can already see the impact of climate change on the glaciers in New Zealand with many already beginning to melt and get smaller. Glaciers in the Southern Alps in the South Island are estimated to have lost more than 30% of their ice volume over the last 40 years.

Activity – pressure melting

Pressure melting helps glaciers to slide downhill.

What you need:

- 2 ice cubes

- A clean, smooth surface such as a table or bench

- A paper towel

Instructions:

- Take the ice cubes out of the freezer.

- Place them side by side on the counter with the largest and flattest sides down.

- With a folded paper towel press straight down on one of the ice cubes for 30 seconds.

- Do you see water forming on the counter? If not, repeat for 1 minute.

- Compare to the ice cube that had no pressure applied. Is there more or less water around it?

- Can you slide the ice around on the counter over a thin film of water more easily than without?

Explanation:

The pressure on one ice cube speeds up melting compared to the one with no pressure. This creates a layer of water between the ice cube and the surface, reducing friction and making it slide more easily. This is similar to the process that happens with a glacier - where the pressure from the weight of the ice creates a melt layer which, combined with gravity, helps the glacier to slowly move down the slope.

Quiz – glaciers

Check out our glaciers quiz. The quiz works best on kahoot, but if you prefer a text version, you can download it as a PDF.