Rob Bell stood on the stage at NIWA’s annual awards ceremony in September for a few stunned seconds and declared: “I’m shocked.”

You could tell he really was by the tremor in his voice and his suddenly-bright eyes, but he would have been the only person in the room the least bit surprised.

Bell had just been presented with a NIWA Lifetime Achievement Award by Climate Change Minister James Shaw, who used his speech not only to acknowledge Bell’s phenomenal contribution to New Zealand, but also to implore him to stay put.

“Please keep it up,” said Shaw. “Don’t stop.”

At 64 Bell is thinking ahead to retirement – not yet, but soon enough to make plans. Under that scenario there will be less travel, more time with his six grandsons, and maybe he’ll finally get around to answering the emails that have lingered in his inbox for way too long.

Bell is a civil engineer by training, guided into his career by an astute teacher who encouraged him to enrol at the University of Canterbury. Bell liked science, but he also wanted to see impacts for his efforts – engineering offered the opportunity to produce practical solutions.

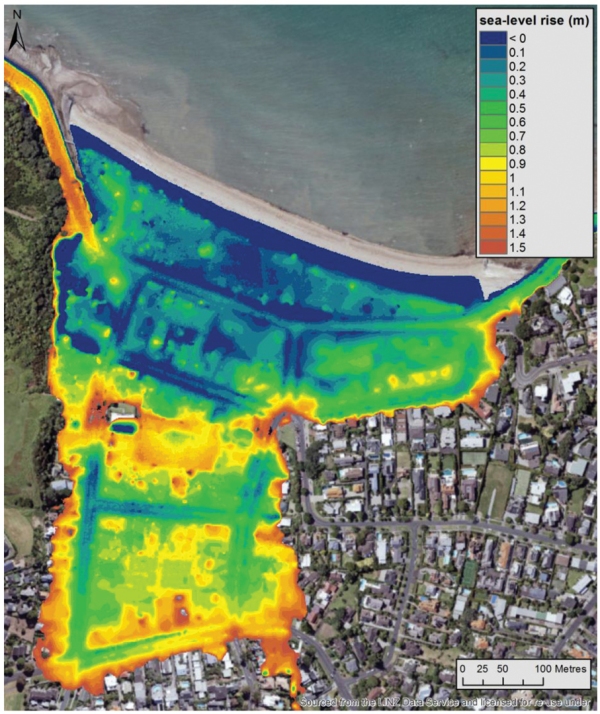

That morphed into coastal engineering, working out ways to clean up wastewater outfall discharges, which in turn evolved into understanding coastal oceanography – tides, currents and erosion – and then being involved in developing a coastal hazard zone for the main subdivision at Coromandel town Pauanui, long before sea-level rise was really a thing.

Bell knew though; the team he worked with at the Ministry of Works included an allowance for it in their final recommendations.

It was the 1980s, and at the end of the decade the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change would be established to provide policymakers with regular scientific assessments on the current state of knowledge about climate change.

“I got really interested in the sea-level component of that – it was the beginning of the stark reality that seas were rising and it was going to be a big issue.”

In 2001, he co-authored the first report for the Ministry for the Environment (MfE) on how sea-level rise would affect New Zealand, along with some adaptation options.

“It was very plain and inauspicious, but it was the start of the journey.” Today Bell is one of New Zealand’s leading sea-level rise experts.

He remains at heart, and in practice, an engineer dedicated to making a practical difference, and while at times he has taken a “deep dive” into science research it’s always been with the end goal of solving a problem.

“I think engineers are taught to be innovative and think outside the box. There is a drive to come up with something concrete that is going to work. Science can be more theoretical at times and you don’t necessarily have to come up with a tangible solution – you might just want to improve the knowledge of something.”

Bell describes himself as a member of a loose group of people he likes to call the “dot joiners”.

They are among the planners, engineers, scientists, academics, council staff, iwi representatives and others working to find a way forward for coastal communities grappling with the complex issues forced on them by impending sea-level rise.

Being a dot joiner means being able to see connections, to look beyond your field of expertise and consider the whole system, to ask questions when nobody else is and motivate others to work in a similar fashion.

Bell gives an example of an engineer designing a bridge.

“A good engineer would consider the concept that this is not just a bridge, but something that serves a community. And perhaps there’s something that could be included in the design, such as flood control works, that might benefit the community in other ways.”

Bell may be a natural dot joiner, but the trait is fuelled by a realisation he came to some time ago that issues caused by sea-level rise could not be solved by science alone.

“In the early days I did a lot of technical work, but much later it dawned on me that this is about people, funding, economics and equity – far more than it is about technical science.”

At the end of 2017 MfE released its latest Coastal Hazards and Climate Change Guidance report, again with Bell at the helm along with Victoria University researcher and long-term colleague, Dr Judy Lawrence.

The pair toured the country after the report was released to lead a series of workshops for council staff, engineers, planners and infrastructure managers to help convey what was essentially a blueprint for how councils should be planning for climate change.

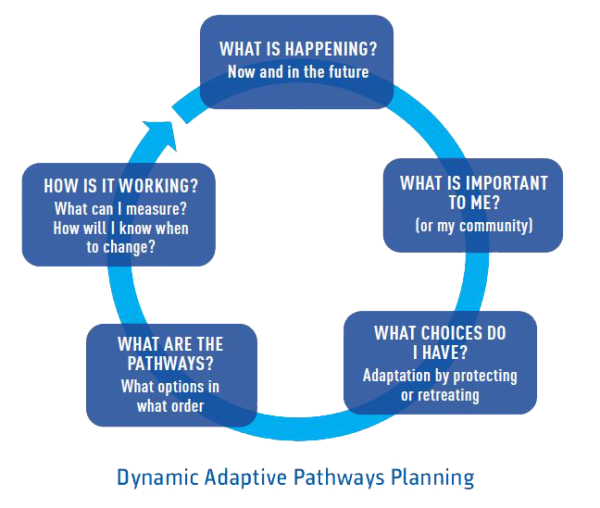

The guidance report included a method of using a process known as Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning. It’s a concept pioneered in the Netherlands and introduced to New Zealand by Lawrence. At its core, Dynamic Pathways Planning embraces the uncertainty that surrounds climate change.

It encourages communities to consider many different options, how long they might be effective for and to understand when it’s time to change tack. Bell calls it the “most versatile tool in the box”.

“Each coastal situation is different – some issues are imminent, and some are down the track, so councils and communities need to work out when they have to adapt and what short- and long-term options are available to them. When they near a threshold they can then decide which of the options they want to implement.”

It was trialled in Hawke’s Bay, where councils and communities were locked in a cycle of finger-pointing and blame over coming to terms with continuing coastal erosion. Dynamic Pathways Planning helped break that paralysis.

Part of its success is due to the way members of the community were included in the process. “We started with a grass roots, bottom-up approach and asked ‘it’s your process, it’s your coast, what would you like to see in the long term?”

It is a lesson that has been hard learnt. Planning for sea-level rise on the Kapiti Coast turned to custard, says Bell with characteristic understatement.

To cut a very long story short, it all ended in court.

“That’s why it’s essential to take a multi-disciplinary approach and include social scientists who understand the dynamics of communities and in particular their strong attachment to place. People want to live at the coast, they want to stay at all costs – that’s what you’re up against.”

Bell says it’s slightly different for iwi and hapū who have been connected to the coast for eons. “You have to understand the whole kaupapa of a particular hapū before you get into any technical stuff.“

There is one place, however, where they are getting it – the University of Canterbury School of Engineering.

Funny how time flies. Last year Bell was invited back to his old university to deliver a lecture series to engineering students as part of a new course entitled Sustainability and Climate Change for Engineering. Now compulsory for second-year professional engineering students, it’s a course about adaptive planning principles and infrastructure.

Bell developed the lectures from scratch and he loved it. “I really enjoyed the interaction. Here we have 180 young engineers who will be going out armed with how to do Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning and adaptive design for our infrastructure.

“To me that was a real buzz, to pass on my knowledge, skills and enthusiasm, because there is a bright future if they can come up with some really creative solutions.”

Bell, along with Lawrence, was named on Stuff’s Climate Change Power List in September that identified a group of New Zealanders with the greatest influence over climate change issues in this country. And as well as receiving NIWA’s Lifetime Achievement Award, he was the joint winner of the NIWA Science Communication Award. Then in November Science New Zealand awarded him a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Colleagues, contemporaries, and workmates speak of Bell with one voice. They value his mentoring skills and willingness to make time to review others’ work and provide quality feedback. He is, they say unanimously, inclusive, humble, always positive and respectful.

Perhaps the greatest accolade comes from a younger scientist who chose his career path because Bell helped him out as a student.

“He is just a genuinely lovely person who wants to help.”

Bell would like a lighter workload, but is torn by the knowledge that there is still much to do.

“I’ve never been very protective of my knowledge and skills and I like sharing them because that’s how change is going to happen.”

At NIWA’s Excellence Awards ceremony in September, after first thanking the team of people he works with, he had one final comment: “May the young ones go for it.”

If you ask Bell whether New Zealand is where it needs to be to deal with sea-level rise, he is optimistic – with provisos.

“There is some criticism that scientists and the IPCC haven’t made it patently obvious that we’ve got a major issue. But what I’ve found is that councils – until recently – haven’t had the tools or the wherewithal to go out to communities to talk about how they’re going to adapt. They’ve been sitting on the side asking for national and central government guidance which they now have – to some degree.

“So now they’re in a phase where they’re trying to get their heads around it and need a lot of help just to put a plan together so it doesn’t end up turning toxic. It takes time, but momentum is building.”

He is also aware that some huge transformational changes will be required – particularly around accepting that there will be a need to retreat from low-lying coasts and harbours.

“There are ways it can be tackled, different ways of doing things, land-use change; a whole raft of creative thinking we can do rather than the traditional approach of just building a house on land at the coast.”

In September, MfE, issued the framework for the first national climate change risk assessment for New Zealand, which will provide an overview of how the country may be affected by climate change. The assessment will be used to prioritise actions to reduce risks or take advantage of opportunities. Bell was on the expert panel for the framework and is now part of the team doing the risk assessment.

That’s just one commitment. The territory occupied by a dot joiner means being on expert panels, working groups, technical committees and at the beck and call of ministers and their officials. Bell admits he’s probably too responsive, but he sees opportunities and can’t help himself. At the moment he is involved with three business cases going to Cabinet for funding, although he did say he turned down a fourth.

“The first thing I do if I get given a policy document is do a word search for climate change and adaptation. If they’re not in there, I ask why. I’m not naturally provocative, and I often sound like a broken record because I see so many places where people are not getting it.”

On climate change deniers:

“There’s a very small minority of hard core deniers out there, and they’ve become more aggressive of late. I’ve had a few emails from them – it’s like a last ditch stand and it gets a bit disheartening at times.”

On media:

“There’s so much more media interest in sea level now.

“I don’t naturally shine to media, but climate change is all about communication, and if we can’t do it and we don’t do it, we’re dead in the water.”

On the future:

“There are ways we can tackle sea-level rise, but it will require some huge transformational changes. There’s a whole raft of creative thinking we need to do.”

“I think there is going to be upheaval for a lot of communities, and we haven’t yet solved the big questions around equity and who pays.”

Hawke’s Bay is no stranger to problems at the coast

The sea has been eroding property and infrastructure from Tangoio to Clifton for decades; some homes have been abandoned and some protected by sea walls and concrete – hoping against hope, and science, that they will hold on.

Hastings District Council principal advisor district development Mark Clews says the finger-pointing and blame over what to do has been as relentless as the tides – or at least it was until 2014.

That’s when the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council, the Hastings District Council and the Napier City Council realised there needed to be less “us and them” and more “we’re all in this together”. So they committed to working with residents on a strategy that would last for the next century.

It required a fresh start and a leap of faith – and a new way of looking an old problem: Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning provided the answer. Developed in the Netherlands and introduced to New Zealand by Victoria University researcher Dr Judy Lawrence, Dynamic Pathways allows for a planning approach that includes uncertainty.

This is particularly useful when considering what to do about the consequences of climate change which brings with it the uncertainty of knowing what might be done to slow its progress.

Clews says Dynamic Pathways allowed everyone to start thinking that there were multiple solutions and that not every decision had to be made now. “It opened our minds to different ways of doing things.”

Panels comprising ratepayers, residents and council staff developed weightings and criteria for ideas and recommendations for their preferred pathways. Clews says they quickly realised that Hawke’s Bay residents who didn’t live at the coast also had a huge vested interest in what was happening, so additional members were added to the panels to represent that perspective.

Eventually the panels will help identify trigger points, the time at which something happens that requires the community to get together again and consider staying on the same pathway or choosing a new one.

“While we know that managed retreat is ultimately the only viable option long term and will eventually happen, the pathways allow us to buy time. We still have quite a long way to go, but at least we have agreed on the preferred pathways to go forward.”

Lawrence and other experts observed the process in action, given the status of “critical friend”. According to Clews they also provided reassurance to the community panels that there were respected academics watching on.

But key issues remain, particularly around the design, the evaluation and implementation and who pays. There is also the need for some immediate work to shore up parts of the coast until the long-term plan is decided.

Clews admits there is some impatience creeping in, which is worrying.

“We are finding that robust debate takes time. Who is responsible for undertaking and maintaining works? Where is the government in this? How do we work out the private/public funding split? How does a managed retreat actually work in practice, and what does it look like for the homeowners and agencies involved?"

“We are not at the end by any stretch of the imagination.”

This article forms part of Water & Atmosphere 23, read more stories from this series.