New Zealand’s first kingfish farm is scaling up production.

Jessica Rowley heads to Ruakākā to get a firsthand look at a two-decade research journey which is unlocking new aquaculture opportunities for New Zealand.

“Be careful. There is a lot of water here.”

This safety warning comes as we wrestle on our slightly-too-small, company-supplied gumboots. We are at NIWA’s Northland Aquaculture Centre, home to the recently completed Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS).

In front of us are eight huge, circular, concrete tanks. So big, that to see inside we have to climb a flight of metal steps onto a viewing platform.

As we reach the top, the first things to capture our attention are the tanks’ scale – each contains 350,000 litres of treated, recycled seawater – and then, the beautiful fish swimming around inside, in mesmerising synchronicity.

These yellowtail kingfish, or Haku, are the result of almost two decades of meticulous research and applied science. Fish that are destined for high-end dining tables, around New Zealand and across the globe.

The fish are strong, healthy and, according to many of the country’s leading chefs, very tasty.

“We are finally at a stage where we can get these fish in front of customers in New Zealand and abroad, at a commercial scale”, says NIWA aquaculture technician and kingfish ambassador, Jeremy Singleton.

Singleton is an ex-chef who has worked at an impressive roll call of top restaurants in both Wellington and Melbourne. He is giving us a tour of the facility, beaming over the tanks.

“I moved to NIWA after years working in fine dining, so I know how difficult it is to find a reliable source of quality seafood. The fish we have here, they’re incredible – a chef’s dream.”

Aquaculture is big business

More than three billion people around the globe rely on seafood as a source of animal protein and, with ongoing declines in wild fish stocks, more than half the fish consumed worldwide are now produced by aquaculture. Some of the highest industry growth rates have come from farming high-value finfish like salmon.

However, farming fish at sea is not without its issues. As climate change continues to warm and acidify our seas, and parasites and disease become more prevalent, operating in the ocean is increasingly problematic.

Both internationally and locally, the industry is moving coastal sea pens out into deeper, cooler waters to address some of these concerns, along with disquiet over the accumulation of food waste and the industry’s environmental footprint. So, how can aquaculture continue to meet the ever-growing demand for high quality, healthy protein, while at the same time mitigate its environmental challenges?

One answer – move it on land.

Kingfish – the ideal candidate

Take yourself back to the early 2000s. Apple unveiled the first iPod, Lord of the Rings – Return of the King scooped 11 Academy Awards, and 'blog' was Merriam Webster's 2004 Word of the Year. At about the same time, NIWA was reviewing its aquaculture science strategy.

“We wanted to develop a new high-value fish species that could meet market demand,” Dr Rob Murdoch tells me.

Murdoch is NIWA’s General Manager for Science and Deputy Chief Executive. He has a special interest in marine ecology and has been with NIWA since the genesis of the RAS.

“New Zealand’s aquaculture sector desperately needed to diversify into high-value species if it was to meet its growth aspirations to become a billion-dollar industry by 2025.” That target later became $3 billion by 2035.

“We saw a clear problem – and an opportunity.”

The first challenge was to identify the right species – ones with an uncomplicated life cycle and commercial potential.

“We’d researched several different options, but it was hard to find a good candidate. Scampi, for example, are incredibly cannibalistic. Put two in a tank, and only one is coming out.”

After myriad investigations, yellowtail kingfish (Seriola lalandi) moved squarely into frame. Known more affectionately as 'kingi', these fish are also called amberjack and are found throughout the warm-temperate waters of the southern hemisphere and in the northern Pacific. They have a simple life cycle and a rapid growth rate.

They are also highly valued and already established within the aquaculture industry. In some places across Europe, companies are even stopping salmon aquaculture and moving to kingfish, because of their higher return.

“We had our ideal candidate,” says Murdoch.

To expand their portfolio and maximise potential return on investment, the team also decided to trial hāpuku. This is an equally promising colder water species, meaning there was potential to grow species at either end of the country.

Now they had their target species, Murdoch and his colleagues returned to their vision for the end product – a high quality, healthy fish sought after in premium markets because of its exquisite taste, provenance and environmental credentials.

The production system and supply chain needed to be constructed and operated in a sustainable and ethical manner to ensure superior fish health and welfare. It needed to provide efficient conversion of raw materials and energy, waste capture and treatment, and an overall low environmental footprint. The system was also required to deliver direct benefits to the local community and, finally, profitability.

“Initially we were considering sea-cage production, but in the end the answer was obvious – a land-based aquaculture system. They were already doing it in Europe with great success, so why not here?” says Murdoch.

Taking control

“We don’t see RAS as a replacement for ocean aquaculture, rather as an addition to sea-caging. The beauty of it is that you can control many of the problems that ocean-based farming has,” says operations manager Steve Pope, pointing at a panel worthy of a spaceship.

“Everything is monitored by machines, but controlled by a team of experts – temperature, oxygen levels, lighting, you name it. We want to grow the stock as efficiently as possible. Luckily, this is where NIWA’s science comes into play – we are dab hands at experimenting.”

Over the years, fisheries experts have narrowed down the perfect conditions to get the biggest and best quality fish. And, crucially, the healthiest and happiest.

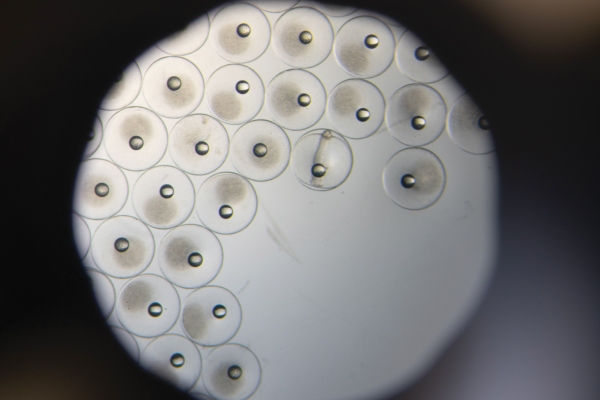

It has taken years of applied science, but the broodstock programme has resulted in significantly higher growth rates. What starts off as an egg the size of a full stop, becomes a 3kg fish in less than 12 months. The fish can also be spawned at any time, which promises a constant supply year-round.

“As you can see, they’re a hungry species”, says Pope, as his colleague launches trowels full of specially developed pellets into the water, kicking off a feeding frenzy.

“We’ve developed our own systems. This food, for example, is highly digestible and causes the faeces to stick together, meaning we can remove the waste much easier.

“We get rid of ammonia too, which is toxic to fish. Ammonia is produced when they metabolise protein. To overcome this, we grow bacterial colonies which consume and convert the ammonia into a non-toxic state.”

With fish living together in close proximity, carbon dioxide build up is inevitable. The RAS uses a process called degassing – which does what it says on the tin. Metal cylinders spew out vast amounts of bubbles, which froth up over the top and cascade down the sides. Exactly what you’d imagine a science experiment to look like.

“We vigorously bubble large volumes of air through the water to get rid of the carbon dioxide,” says Pope.

“Carbon dioxide moves from the water into the air, and we then pump the water back to the fish. Just before it enters the tank, we add oxygen to ensure the fish are never deprived or distressed.”

The equivalent of one 350,000-litre tank of water goes through the process every 20 minutes. When the tanks refill, an impressive 98 percent of the water is reticulated through the system.

Nursing the next generation

The number of eggs that a single female fish produces is mind-boggling. In just a week, they can spawn two million eggs. Within their two-month spawning season, that’s over 10 million. But there is a good reason for this. In the wild, a minuscule number will reach maturity – on average, only two, in fact. The rest die from trauma, disease, or in the stomach of a hungry predator.

However, NIWA’s kingfish are not in the wild.

“Eighty percent of our eggs hatch and about four to eight percent grow into adult fish. Compared with survival in the ocean, that survival rate is off the charts,” says Singleton.

When the eggs hatch, the larvae are transferred to a nursery area where they are fed a range of tiny aquatic animals, before being weaned onto a specially formulated diet after a few weeks. They are transferred to larger tanks as fingerlings, before being transferred again into the RAS tanks, where they continue to grow rapidly.

Once they reach market weight (3kg, after about 12 months), a small proportion are selected for future breeding. These fish are put on a broodstock diet and breed three to four years later. For the rest, it’s time to be harvested.

Singleton stresses that animal wellbeing is a key pillar of the team’s work.

“Our research shows that kingfish thrive in RAS – circular tanks suit their natural schooling and feeding behaviour.

"The systems for exchanging and refreshing the water are engineered to ensure a consistent, healthy rearing environment. And, because land-based RAS affords full environmental control and exclusion of pathogens or parasites, medications are rarely needed. We care about these animals deeply and do our best to ensure they are looked after,” says Singleton.

In recent years, NIWA has been supplying up to 600kg of premium Haku a week to selected high-end restaurants all over New Zealand and some select international customers. The aim has been to test the market and gather initial feedback on the product.

It’s safe to say, it’s going down a storm. Award winning chef Makoto Tokuyama of Ponsonby’s Cocoro Restaurant describes it as an excellently balanced fish and superior to the wild product.

But the current trial distribution operation is a drop in the ocean compared with what’s now on the horizon.

Dr Andrew Forsythe is NIWA’s Chief Scientist for Aquaculture & Biotechnology, based at Bream Bay. He says the RAS is finally ready to move from science to full commercialisation.

NIWA’s understanding of the market, combined with the biological, technical and financial feasibility of growing these fish, means up to 600 tonnes of Haku kingfish can now be confidently harvested from the facility each year.

Forsythe says the past six months have established the system’s performance, and discussions with commercial partners about marketing the harvested fish are well advanced.

“A single large tank can hold up to 30 tonnes of fish. You can imagine the logistics involved in managing, harvesting and moving all of that. It’s a big operation.

“We have a huge amount of interest already. Not just from the seafood sector, but also from other investors who are keen to get involved,” says Forsythe.

Growth opportunities

Not only does the RAS facility offer fresh opportunities for fine diners and the seafood industry, but it also represents a significant new avenue for regional growth. The current, experimental, commercial-scale operation is located on an eight-hectare freehold title owned by NIWA, with seawater intake and discharge infrastructure to accommodate considerable expansion. A full-scale 3,000-tonne operation could be up and running within five years, creating about 75 new jobs and substantial annual income for the region.

The Northland Regional Council (NRC) collaborated with NIWA in the RAS development, and has its eyes firmly set on regional growth.

NRC’s strategic projects manager Phil Heatley says the council and local businesses identified the finfish sector as a key opportunity when working together on a regional aquaculture strategy almost a decade ago. He says the council was excited by the opportunity to combine this thinking with NIWA’s science expertise.

“The RAS has an ultra-low impact on the environment and it’s using resources efficiently in the production of high-value protein.

“Add to that the benefit of diversification to the current aquaculture market, and the creation of new employment opportunities for the region, and the council couldn’t be more pleased to be involved.”

Northland’s role as the anchor stone of the RAS is self-evident, but the long-term implications of the development could yet reach much further.

The technology has been deliberately developed to enable it to be readily replicated for both different species and different locations. Work is already well advanced on adding hāpuku to the RAS stable. The system is also capable of being set up in multiple locations, provided there is an adequate source of seawater nearby.

Given New Zealand has the ninth longest coastline in the world, the options are far from limited. Whatever the years ahead hold, with worldwide demand for high quality, low-impact, sustainable seafood ever growing, the future for the RAS and Haku kingfish in the North looks exciting.

Cocoro’s Tokuyama, for one, has few doubts.

He says Haku is firm and crisp, with a really clean flavour, and customers love it.

“This is one of the best farmed fish in the world – even compared with the quality of Japanese-farmed fish.

“Haku is amazing.”

This story forms part of Water and Atmosphere - November 2023, read more stories from this series