At a pristine, isolated lake near Otorohanga in the Waikato, NIWA freshwater biologist Brian Smith recently made an important discovery.

It’s only 2mm long and, according to Smith, a bit dull to look at, but it is unlikely to be found anywhere else.

Smith’s discovery of a new species of caddisfly was made during a survey of tiny Lake Koraha. The lake’s isolation, combined with the size of the newly discovered insect, Smith says, are probably what allowed it to escape detection for so long.

“It’s very small and easily overlooked, but this is related to another species of caddisfly discovered in Hamilton about five years ago.”

Caddisflies are related to butterflies and moths and there are about 250 species that are unique to New Zealand.

“They’re mostly nocturnal and dull, drab looking things, but it’s great to have found an adult male inside the pupa case that enabled it to be identified.”

Smith will get to name the new species, but is yet to decide just what to call it.

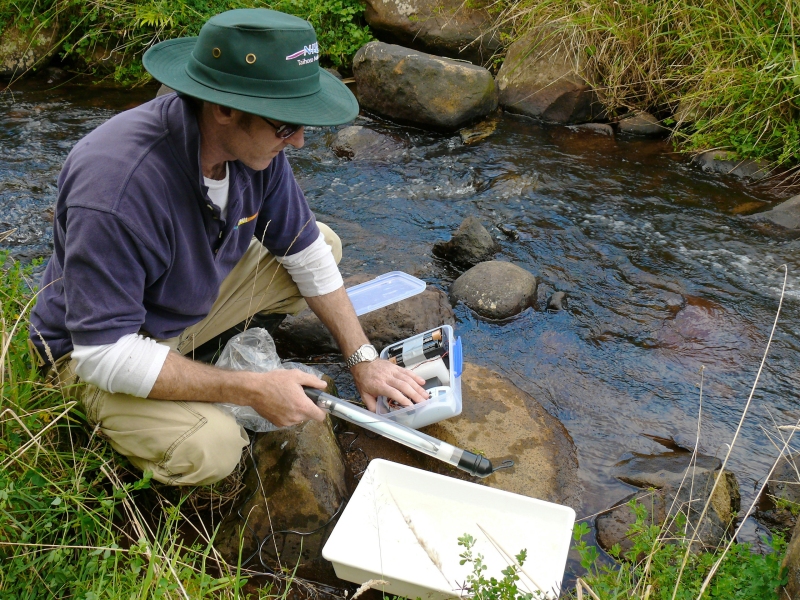

Meanwhile, a random decision to turn over a boulder at the Tukituki River in Hawke’s Bay resulted in a second caddisfly discovery for Smith.

“I was doing some work at the Tukituki when I happened to pick up a rock. It was a totally off-the-cuff thing to do since it was out of the water, not in it. I noticed that on the underside some bugs were feeding on caddisfly eggs.”

Caddisflies often lay their eggs on partly submerged rocks, but receding floodwaters meant the rocks were no longer submerged, leaving the eggs high and dry – and an ideal food source because they are rich in nutrients and protein. What Smith quickly noticed was that the insects feeding on the eggs were land based and had become opportunistic predators.

“This was a unique interaction between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems that highlights how changes in water levels during critical stages like egg laying may have dire consequences for some aquatic insects,” Smith said.

This world-first observation is now the subject of a scientific journal paper.

Smith has also recently finished a four-year study of adult aquatic insects that provides new and updated ecological information for more than 70 species of mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies, filling an important knowledge gap. But he warns that information about the adult life stage of even our most common species lags far behind that of the larvae.

“It is important to understand all the life stages of an insect because any one of them might be affected by changes in the aquatic environment and its surroundings.”