Overview:

Sharks are vulnerable to overfishing because of their low reproductive rates and often low growth rates. Tuna longline fisheries, which operate mainly in oceanic waters beyond the continental shelves that surround land masses, catch many pelagic (open-ocean) sharks, including shortfin mako sharks (Isurus oxyrinchus).

Most pelagic sharks fall near the middle of the shark productivity scale, and there is concern that catching too many of them could lead to population depletion. In New Zealand waters, mako sharks are the second most commonly caught shark species (after blue sharks) on tuna longlines. They are not targeted but are taken as bycatch.

Game fishers have been tagging makos with plastic dart tags for decades, and the results show that makos move around the southwestern Pacific, with some travelling from New Zealand to eastern Australia and the tropical islands to the north of New Zealand. However, plastic tags provide no information on when the sharks moved between the tag and recapture locations, how long they took, and what route they followed. They also tell us nothing about their mobility, or their preferred habitat. We need such information to inform the best management method: if mako sharks are wide-ranging wanderers in the open ocean then their management should be at a large scale and involve multiple countries. But if makos are less mobile and remain in a small area for long periods, then local management is more appropriate.

Approach:

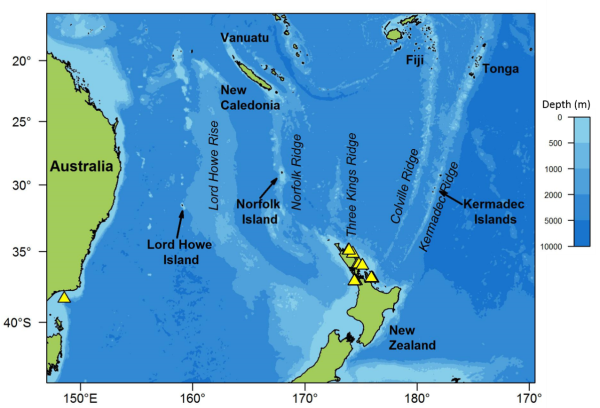

We deployed electronic tags on 14 mako sharks that were 150–240 cm long. Most sharks were juveniles but they also included several adult males; these groups make up the majority of mako sharks caught in New Zealand (mature females are rarely seen). Sharks were caught around northern North Island by angling from small motorboats. One was also tagged in southeastern Australia. They were brought to the vessel and restrained alongside in the water while the vessel motored forward at about 1 knot, maintaining a constant flow of seawater over the gills.

Tags were fixed to the dorsal fin, from where they can communicate with Argos satellites whenever the dorsal fin breaks the sea surface. Shark locations, water temperatures, and in some cases depths, are transmitted via satellite back to NIWA.

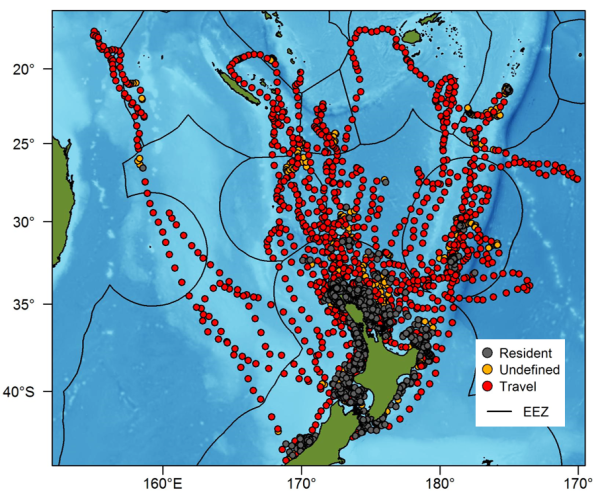

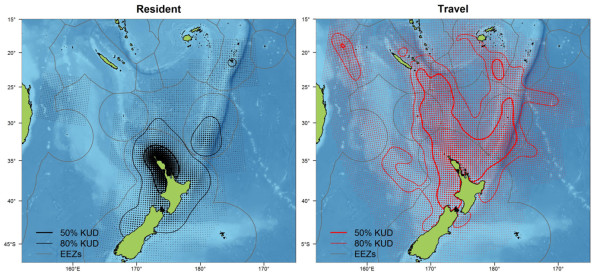

A mathematical model was used to fit smoothed tracks to the location fixes, and to identify two types of shark behaviour: 'Resident' behaviour was defined as periods of slow movement with frequent course changes, and 'Travel' behaviour was defined as periods of relatively fast and straight movements.

Outcome:

All mako sharks were tagged in shelf waters, and all except one subsequently travelled into oceanic waters. Most sharks exhibited highly variable movement. At times, they spent up to several months continuously within a strip of the New Zealand continental shelf less than 200 km long; at other times they made long-distance ocean crossings of more than 1,000 km. Oceanic movements often took sharks to the tropical and subtropical islands north of New Zealand, including Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Chesterfield, Norfolk and Kermadec islands. Maximum displacements from the tagging locations were 311–2,904 km with 12 out of 14 sharks exceeding 1,000 km. These oceanic journeys often culminated with a return to the New Zealand shelf, sometimes ending up very close to the tagging location. Total distances travelled ranged from 2,000 km to 20,000 km (average 10,000 km). The percentage of time spent by mako sharks in the New Zealand Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) ranged from 42% to 100%; five of the 14 sharks spent more than 90% of their time in the EEZ.

Nearly half of the total track time was classified as Resident, and one-third as Travel (with the rest being undefined). Resident behaviour was concentrated around the coast of New Zealand, while Travel behaviour was widespread through the southwest Pacific as well as near the coast of New Zealand, and was often associated with the submarine ridges running north of New Zealand.

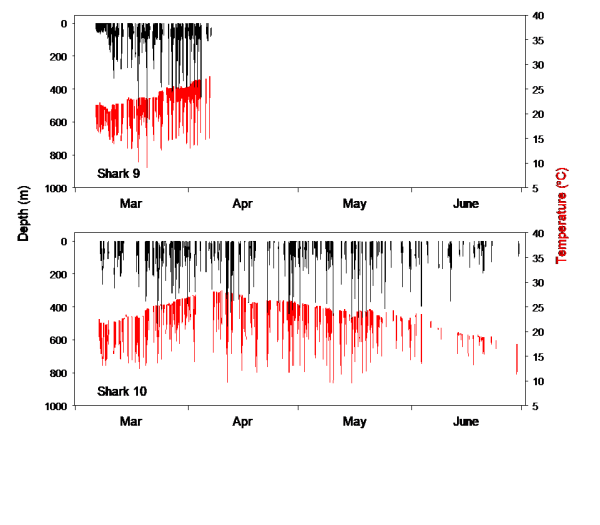

Two sharks with tags containing depth sensors made frequent vertical movements between the surface and 300–400 m depth, and reached maximum depths of 515 m and 605 m respectively. However, both sharks spent most of their time shallower than 100 m. Nearly all deep diving occurred during the day. Water temperatures for these two sharks covered a wide range of about 9–28 oC, with most of their time being spent at 14–27 oC. Temperatures below 17 oC occurred mainly during deep dives. Temperature data for most of the other eight sharks with temperature sensors showed that they too were diving deep while in oceanic waters. Mako sharks are warm-blooded and can maintain their core body temperatures 6–8 °C above ambient temperature.

Mako sharks tagged in this study spent most of their time in the New Zealand EEZ, which challenges the conventional view that they are oceanic wanderers. However, larger adult males and adult females may be more mobile than the mainly-juvenile sharks we tagged, and further research on them is required. The tendency for small to medium mako sharks to remain within a restricted coastal area for several months, and to travel beyond the 200-mile EEZ limit only occasionally, indicates a relatively high degree of residency that must be considered when managing fishery removals. In New Zealand, mako shark abundance may have declined during the late 1990s and early 2000s, but since then it has steadily increased. New Zealand manages its mako shark catches with a 200 t Total Allowable Commercial Catch, although recent landings have been below 100 t per year. But because New Zealand makos periodically interact with those found in tropical waters to the north, a stock assessment of the entire southwestern Pacific mako shark population is needed to determine its current status.