Observations of a Pacific atoll mangrove forest over the last several years by a NIWA-led research team suggest that mangrove systems on oceanic atolls may lose the race to keep pace with sea-level rise.

These findings are consistent with previous studies which show global sea level rise, driven by climate warming, threatens the future of mangrove forests that fringe the shorelines of temperate and tropical regions, including New Zealand’s upper North Island. Mangroves cannot be permanently submerged, so must maintain their position in the intertidal zone by accreting mineral and organic sediment. Consequently, sediment supply is critical to the resilience of mangrove forests to sea-level rise.

The tropical Njimec mangrove forest on New Caledonia’s Ouvéa Atoll is devoid of mineral sediment from rivers so provides an exceptional natural laboratory to study the sediment poor end-member mangrove forests found on atolls throughout the Pacific.

In these atoll systems, sediment is supplied entirely from biological sources, such as carbonate-producing animals and plants (i.e., coral, algae) and the leaf litter and woody debris generated by mangroves. But on the Ouvéa Atoll, research shows sea levels are rising faster than the mangrove forest can gain elevation and some species may struggle to survive. This is particularly the case for the large-leafed orange mangrove (Bruguiera gymnorrhiza) that is more sensitive to inundation than the other common species, red mangrove (Rhizophora stylosa), that occurs in the Njimec forest.

Sea-level rise poses a different challenge for New Zealand’s coastal mangrove habitats. In some estuaries, rivers will deliver sufficient sediment for mangroves to gain sufficient elevation to be resilient to future sea-level rise. But in sediment-poor systems, mangroves will need room to retreat inland as the sea level rises.

The Future Coasts Aotearoa Endeavour research programme is addressing how coastal wetlands in New Zealand will respond to sea-level rise and identify opportunities for wetland restoration in lowlands as they salinize and inundate.

International research

Andrew Swales, Principal Scientist (Coastal and Estuarine Physical Processes) at NIWA, is leading the research on Ouvéa Atoll with a team of coastal wetland scientists from New Caledonia, Australia, United States and New Zealand.

The team was awarded a National Geographic Society Explorer Grant in 2019, to continue research initiated on Ouvéa in 2017, with support from the French Pacific Fund (Project: MANA’O Les mangroves d’Ouvéa).

Monitoring equipment was installed in the Njimec mangrove forest in 2017.

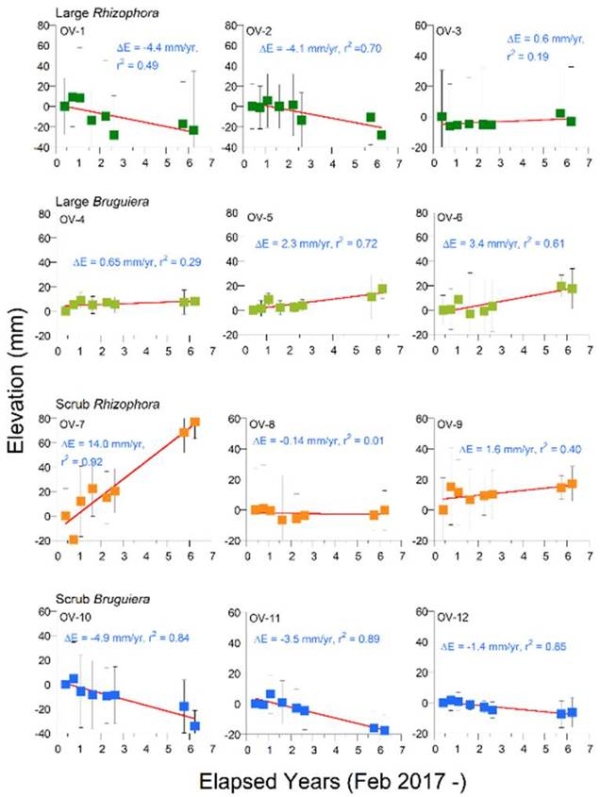

This equipment included Rod Surface Elevation Table (RSET) deep benchmarks in large and scrub stands of the Bruguiera and Rhizophora mangroves to measure trends in sedimentation, compaction and resulting surface-elevation changes.

Water level recorders were also deployed to measure tides and inundation periods while dendrometers fitted to the trunks of the mangroves measure tree growth rates. Nutrient addition experiments have also been undertaken to identify limiting nutrient(s).

Researchers also investigated production of roots and their role in maintaining surface elevation.

Blue carbon inventories from soil cores are being developed and up-scaled with high-resolution worldview satellite images collected on seven overflights of the atoll in 2016–2017 to estimate the role of the mangrove in carbon sequestration.

Sediment cores are being dated (lead-210, Plutonium239+240) to quantify rates of sedimentation over the last century. These data are being used to inform modelling of the future evolution of the mangrove forest under a range of sea-level rise scenarios.

Six-monthly visits were made to gather data until the Covid-19 pandemic halted travel in early 2020. Field work resumed in November 2022.

Analysing the data

Emerging trends from the research help to improve our understanding of mangrove forests’ resilience to climate change.

The RSET data NIWA gathered consistently shows there’s not enough sediment being supplied to maintain substrate elevation in the scrub Bruiguiera mangroves, to keep pace with sea-level rise, with annual surface elevation loss of up to 5 mm/yr.

By contrast, substrate elevation has been increasing in the scrub Rhizophora at up to 3 mm/yr that is similar to regional sea-level rise over the past few decades. This could reflect more efficient trapping of fine carbonate sediment by the dense network of aerial roots or sediment transport favouring deposition in the scrub Rhizophora.

In the large Bruiguiera (tree height ~10+ m), litter deposition and root growth provides sufficient organic sediment for now to drive surface elevation gain of up to 3.5 mm/yr. This suggests that large trees have more resilience to sea-level rise under present conditions.

“Overall, our observations show that the scrub Bruguiera mangroves are in decline with the more inundation tolerant Rhyzophora mangrove opportunistically invading these Bruguiera mangrove stands,” Swales said.

“This difference in inundation tolerance is also demonstrated by water-level measurements. These two years of data show that hydroperiods in the Bruguiera stands (25–32%) are substantially lower than those Rhizophora can tolerate (53–57%). This is likely to be a short-lived bonanza as Rhizophora meet their own inundation thresholds as sea-level rise continues in the next few decades.”

A Pacific treasure

Ouvéa Atoll is a UNESCO World Heritage site, which means it is considered to have outstanding natural and cultural value.

It is a low-lying atoll in the Loyalty Island group, an archipelago northeast of the New Caledonian mainland of Grande Terre.

It has one of the world’s best-preserved mangrove systems while its beaches and coastal marine habitats attract tourists from around the world.

The Téouta tribe is the guardian and beneficiary of the mangrove forest’s natural resources.

Swales said the tribe has shared its knowledge of environmental changes and its people have actively participated in the research study.

Educational outreach and technical training with the people of Ouvéa, University of New Caledonia students and regional government agencies also form part of the research project.

“The mangrove forest is paramount to Téouta culture. It provides a habitat for a lemon shark nursery, and sharks are the totem of Téouta people. Fishing in the mangrove forest provides a source of food and income for families, it also enables people to feed and host visitors.”

Research results

The full results of the study will be shared with the Téouta tribe first, then the New Caledonian community and the international science community. It will provide scientific evidence of the ecological value of mangrove systems and their response to climate change.

“Our research on Ouvéa will help us understand what might be happening to mangrove habitats on other Pacific atolls.

“It can be used for regional or international conservation strategies.”

The United States Geological Survey, a key Future Coasts Aotearoa research partner, is also using data from Ouvéa, Micronesia and Florida to develop a new numerical model.

The model will explore the impact of climate change on Pacific atolls and sediment-poor mangrove forests over timescales of decades to centuries.

Cultural legacy

The Téouta people’s oral history of their Polynesian ancestor’s arrival in Ouvéa in the late 17th century from Wallis (Uvea) Island is intertwined with the Njimec mangrove forest.

Swales and the research team interviewed Monsieur Vincent Adeda, a Téouta tribal leader, as part of the study on Ouvéa. In the interview, Adeda said an oracle told their forebears before departing Wallis (2000 km north-east of Ouvéa) that their journey “would end when they see a mangrove leaf floating and a mullet jumping”.

After circumnavigating New Caledonia (Grande Terre), they found these signs in northern Ouvéa, settling on the upraised coral butte of Motu Unyee that overlooks the Njimec mangrove forest.

Swales said the research team’s efforts had unearthed new strands of knowledge to help the Téouta people prepare for the future.

“I hope our research will convey how their mangrove forest will likely change and how the tribe may plan and adapt to these changes. The research will also fill a gap in present understanding of how mangrove forests on the low-lying atolls sprinkled across the vastness of the Pacific will respond to sea-level rise over the coming decades.”

The current contract for the Ouvéa study will conclude at the end of 2023 but Swales said there is scope for it to continue further.

Research partners

- University of New Caledonia: Professor Cyril Marchand.

- University of Queensland: Professor Catherine Lovelock.

- U.S. Geological Survey: Drs Glenn Guntenspergen, Ken Krauss and Joel Carr.

- Tulane University: Professor Dan Friess.

- Louisiana State University: Professor Sam Bentley.

- University of Otago: Dr Paul Denys.

Related research

- Biogeomorphic evolution and expansion of mangrove forests in New Zealand’s sediment-rich estuarine systems

- Comparison of sediment-plate methods to measure accretion rates in an estuarine mangrove forest (New Zealand)

- The vulnerability of Indo-Pacific mangrove forests to sea-level rise

- The Ecology and Management of Temperate Mangroves