Taonga species such as tuna (freshwater eel), kōura (freshwater crayfish) and kākahi (freshwater mussels) are central to the identity and wellbeing of many Māori.

For generations these species have sustained communities and helped transfer customary practices and knowledge from one generation to the next.

However, many communities are reporting that both the abundance and size of these freshwater taonga are declining. Te Kūwaha, NIWA’s National Centre for Māori Environmental Research has been working with whānau, hapū and iwi for more than a decade to co-develop methods for the protection, restoration and economic development of these species.

Kōura species

Kōura (also known as kēwai) are freshwater crayfish endemic to Aotearoa.

There are two species of kōura in Aotearoa:

- Paranephrops planifrons

- Paranephrops zealandicus

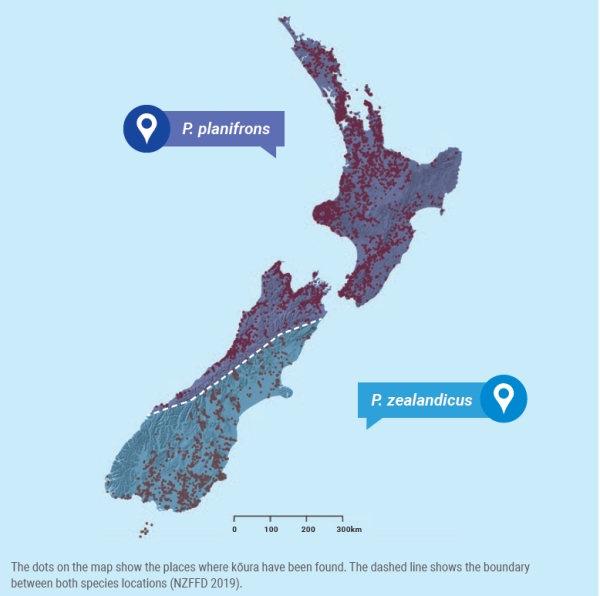

The two species have subtle differences and distinct distributions (they occupy different areas).

Paranephrops zealandicus are generally larger and have very hairy pincers, while Paranephrops planifrons are slightly smaller and have less hairy pincers.

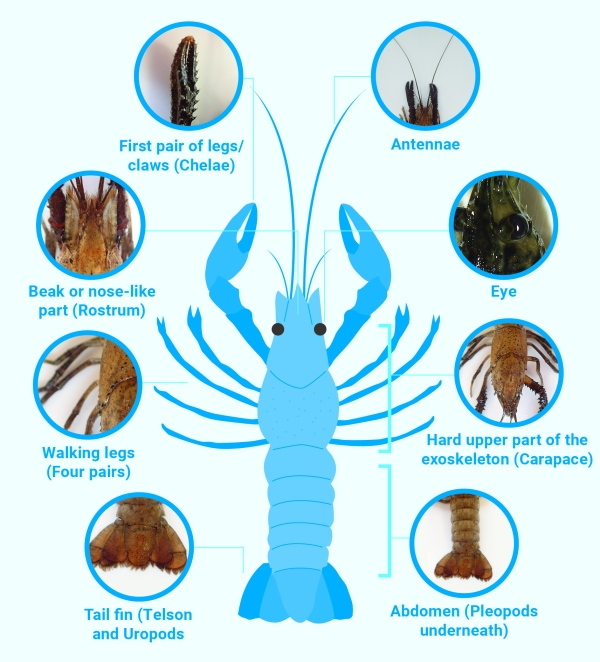

Kōura have their skeleton on the outside, this is called an exoskeleton, which they moult (shed) as they get bigger in size.

During moulting they become soft for a short time as the new outer shell hardens, they can grow back limbs they have lost through a series of moults.

Kōura move by walking along the lake or stream bottom or flicking their tail to swim rapidly backwards.

Kōura anatomy

Kōura Distribution

Our two kōura species are found in distinct locations that don’t overlap. P. planifrons is found in the North Island and in the northwest of the South Island, while P. zealandicus is found along the eastern side of the South Island and on Stewart Island. The two species are separated by the Southern Alps.

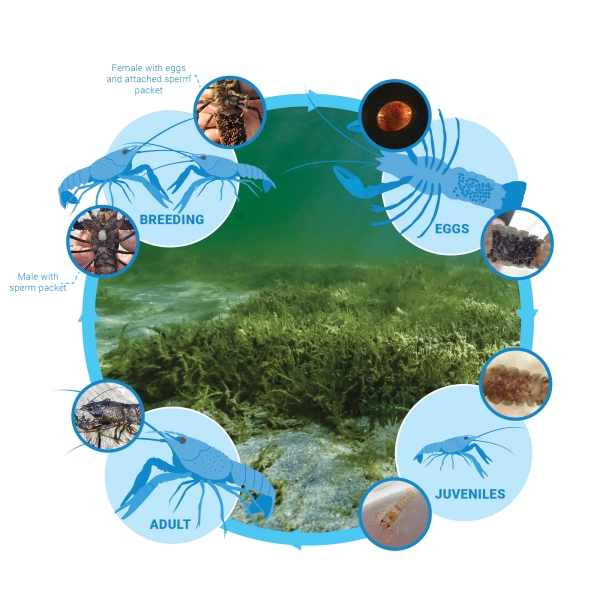

Life Cycle

- Breeding Kōura that live in lakes are thought to have two breeding seasons per year, one in late Autumn and one in Summer. Male kōura attach a packet of sperm on the underside of the female. When the female lays her eggs, they pass through the packet of sperm and become fertilised.

- Eggs A female can have anywhere between 20 – 320 eggs at a time, which are attached to hairs on the underside of her tail. The eggs can stay on the female anywhere between 4 and 15 months until they are fully developed into juvenile kōura – the time it takes can vary depending on the water temperature and species.

- Juveniles Juvenile kōura cling to their mother’s abdomen using their rear legs until they are large enough to defend themselves and live alone.

- Adults It can take kōura between two and four years to become an adult – seasonality and water temperature have an effect. P. zealandicus is slower growing. A fully-grown kōura averages 12 – 15 cm in length when measured from behind the eye to the end of the carapace (called the OCL measurement).

Where do kōura live?

Koura live in lots of different types of freshwater environments. They are found in streams, rivers, ponds, lakes and wetlands in native forest, exotic forest and pastoral waterways. In some wetlands, during the dry summer months when water levels get very low, koura can burrow deep into the mud and then come out again when the water returns.

How do kōura behave?

Kōura are more active at night and usually seek cover from predators during the day. They are highly territorial and need places to hide from each other as well!

They will find shelter almost anywhere including under stones, boulders, logs and aquatic plants. They are also able to make little burrows for themselves in the mud.

In some of our lakes, kōura take predator avoidance very seriously, especially in areas of the lake that are sandy and where they don’t have many places to hide.

For example, at some beaches around Lake Taupō-nui-a-Tia, every night the kōura travel to the shallower areas near the shore (called the littoral zone) to find and eat food. As dawn approaches, they move back to the deeper waters of the lake to take cover.

The daily migration of these kōura has probably evolved to protect themselves from fish - like perch, catfish, trout and tuna, birds like shags and kingfishers, as well as rats.

What do kōura eat?

Kōura are opportunists and eat a wide variety of food. Food for kōura include fish, plants, snails, mayflies and mayfly larvae – live or dead!

Kōura use their strong claws for cutting and catching prey. Their walking legs have small pincers on the end which can be used to sort and pick up small pieces of food. Where there are lots of kōura (high densities), they have also been known to eat each other.

What are the threats?

Across Aotearoa kōura populations are exposed to a range of environmental impacts including things like the removal of native bush, the drainage of wetland areas, too much sediment, eutrophication in lakes (too many nutrients), and the introduction of pest species to our waterways.

Introduced fish species trout, catfish and perch all prey on kōura.

High water temperature, low calcium concentrations, and low oxygen concentrations can all negatively affect kōura populations. Kōura may also be affected by pollutants such as heavy metals or toxins from harmful algal (blue-green) blooms.

Internationally some freshwater crayfish species are being impacted by fungal infections.

How can we help kōura?

Kōura are an important taonga species in our freshwater ecosystems. Some ways you can help our kōura populations include:

- Protect, restore and create kōura habitat. For example, fencing and planting our waterways provides protection, shading, in-stream habitat and food for kōura populations

- Provide good water quality

- Remove pest fish species and aquatic weeds

- Stop the spread of pest fish and plants between waterways by making sure boats and other equipment are thoroughly cleaned.

- Follow harvest regulations and any rāhui in place

Download

- Kōura: What does science tell us about New Zealand freshwater crayfish booklet (PDF 2.9 MB)

- Kōura lifecycle poster - Te Reo (PDF 1.8 MB)

- Kōura lifecycle poster - English (PDF 1.8 MB)

Taonga Species Series

Kōura images