El Niño Southern Oscillation: what is it?

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of a naturally occurring global climate cycle known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO for short. ENSO influences rainfall, temperature, and wind patterns around the world, including New Zealand. El Niño and La Niña episodes occur on average every few years and last up to around a year or two.

Although ENSO has an important influence on New Zealand’s climate, it accounts for less than 25 percent of the year-to-year variance in seasonal rainfall and temperatures at most locations. Nevertheless, its effects can be significant.

El Niño

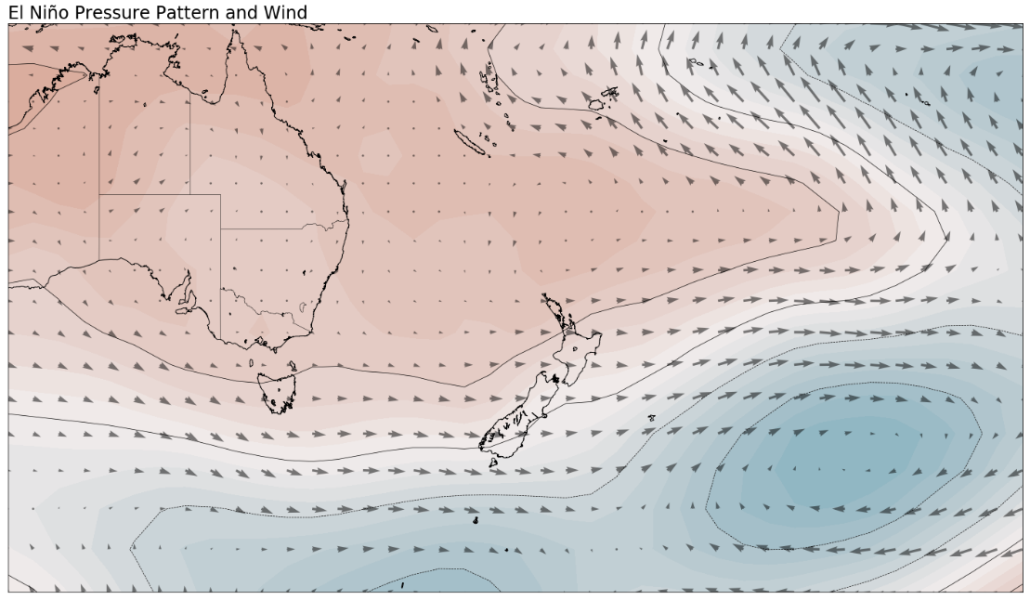

During an El Niño event, ocean water from off the coast of South America (near Ecuador and Peru) to the central tropical Pacific warm above average. The warming takes place as trade winds (the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow around the equator) weaken or even reverse, blowing warm water from the western Pacific toward the east. As a result, sea temperatures in the far western Pacific can cool below average. The unusually warm water in the eastern Pacific then influences the Walker Circulation, acting as a focal point for cloud, rainfall, and thunderstorms. It is this change in the Walker Circulation that impacts weather patterns around the world.

El Niño’s average influence on New Zealand

It’s important to bear in mind that while we know the average outcome of El Niño because of historical data, no El Niño is average—each comes with a unique set of climate characteristics and therefore can be expected to influence the weather differently.

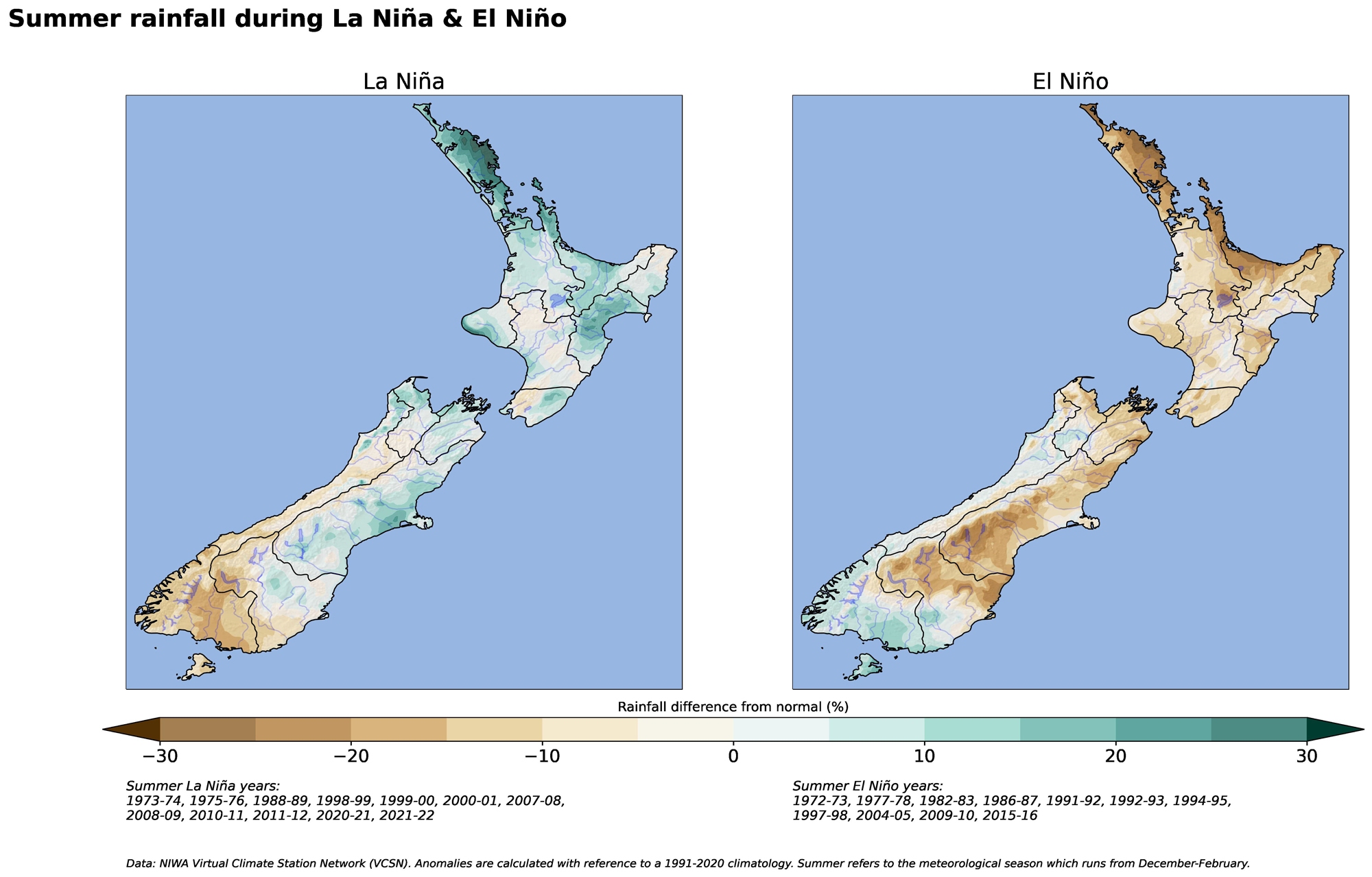

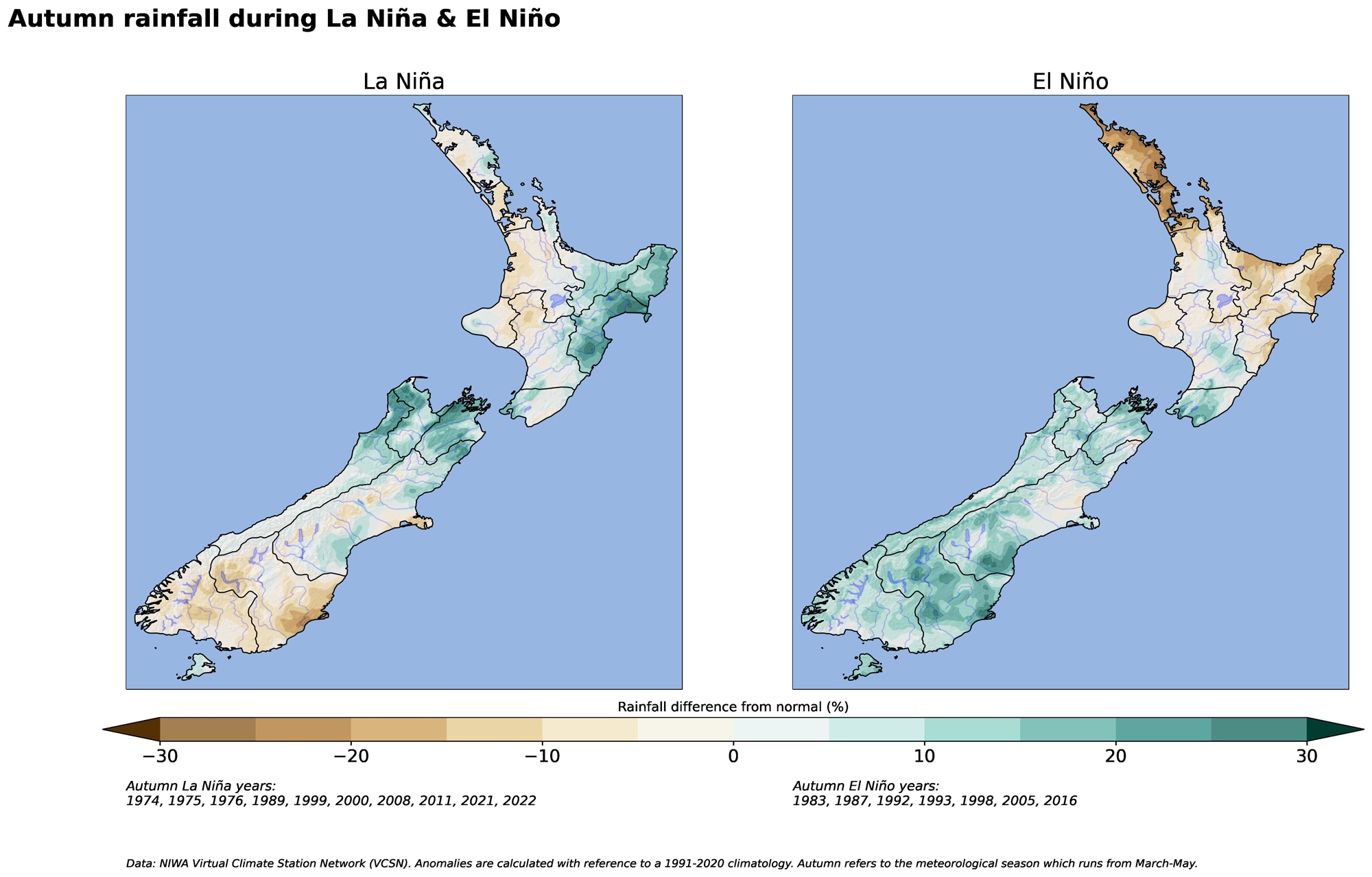

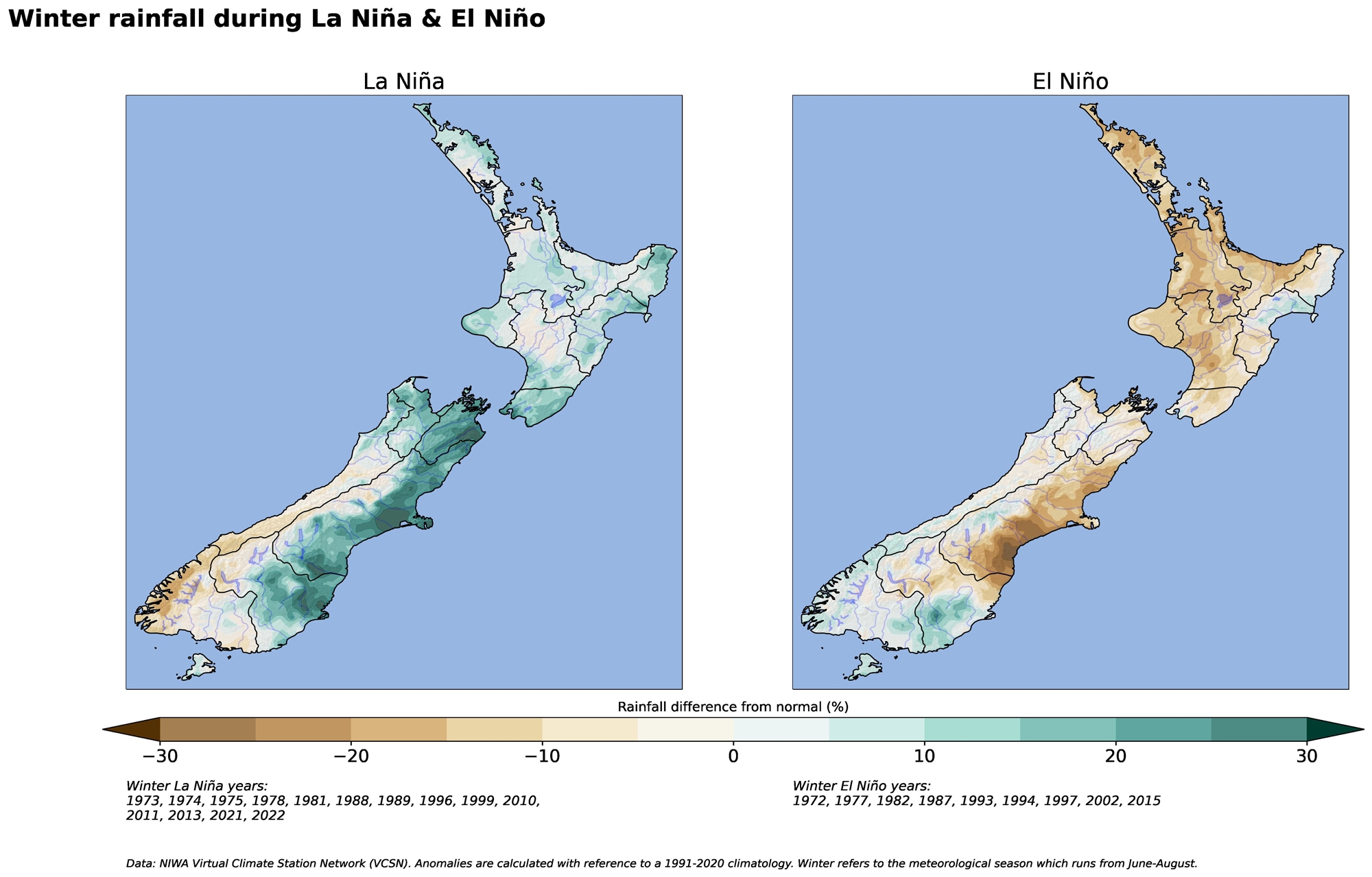

During El Niño, New Zealand tends to experience stronger or more frequent winds from the west in summer, which can encourage dryness in eastern areas and more rain in the west. In winter, the winds tend to blow more from the south, causing colder temperatures across the country. In spring and autumn, southwesterly winds are more common.

La Niña

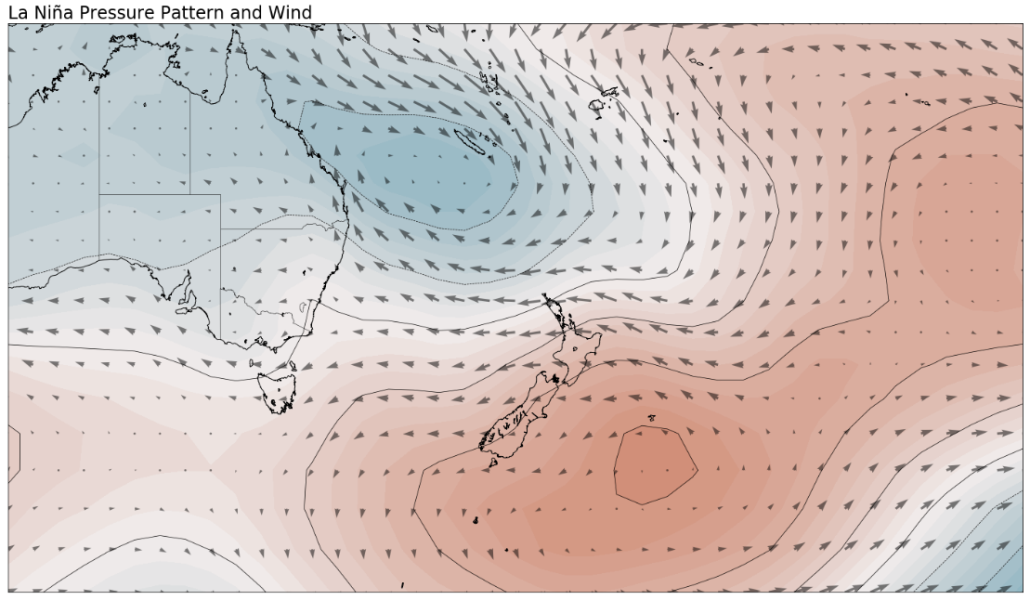

During a La Niña event, ocean water from off the coast of South America to the central tropical Pacific cools to below average temperatures. This cooling occurs because of stronger than normal easterly trade winds, which churns cooler, deeper sea water up to the ocean’s surface. Sea temperatures can warm above average in the far western Pacific when this happens. The unusually cool water in the eastern Pacific influences the Walker Circulation and suppresses cloud, rain, and thunderstorms. This change impacts weather patterns around the world, but in a different way than El Niño does.

La Niña’s average influence on New Zealand

Northeasterly winds tend to become more common during La Niña events, bringing moist, rainy conditions to northeastern areas of the North Island and reduced rainfall to the lower and western South Island. Warmer than average air and sea temperatures can occur around New Zealand during La Niña.

Monitoring ENSO: Southern Oscillation Index

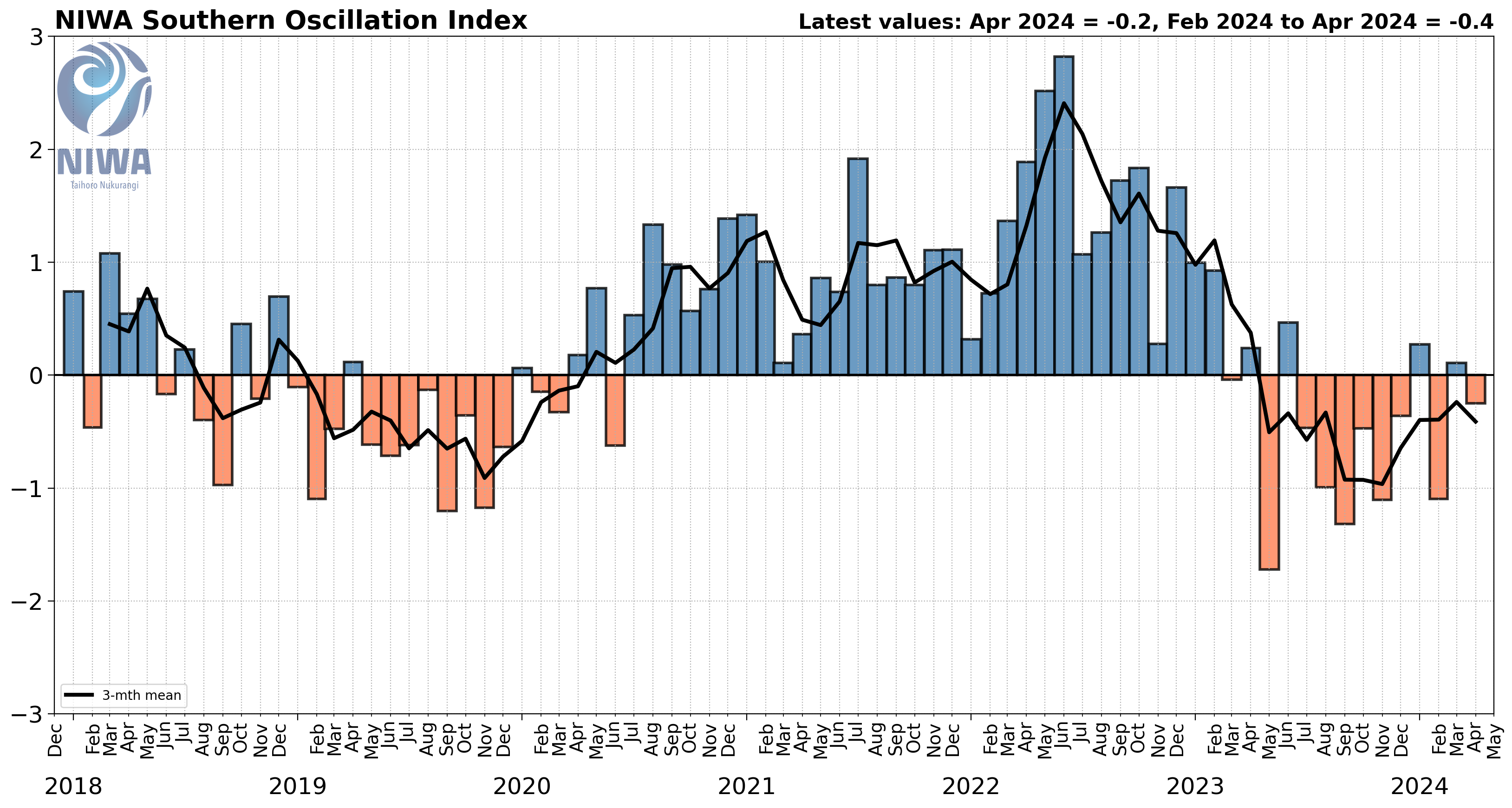

Sir Gilbert Walker documented and named the Southern Oscillation in the 1930s. The clearest sign of the Southern Oscillation is the inverse relationship between surface air pressure at two sites: Darwin, Australia, and the South Pacific island of Tahiti.

Over periods of a month or longer, higher pressure than normal at one site is almost always concurrent with lower pressure at the other, and vice versa. The pattern reverses every few years. It represents a "seesaw" or a mass of air oscillating back and forth across the International Date Line in the tropics and sub-tropics.

The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) quantifies this pressure difference. Over a period of three months or more, values below -1.0 correspond to El Niño conditions while values above 1.0 correspond to La Niña conditions. Values between -0.5 and -1.0 lean toward El Niño, while values between 0.5 and 1.0 lean toward La Niña. Values between -0.5 and 0.5 are considered neutral.

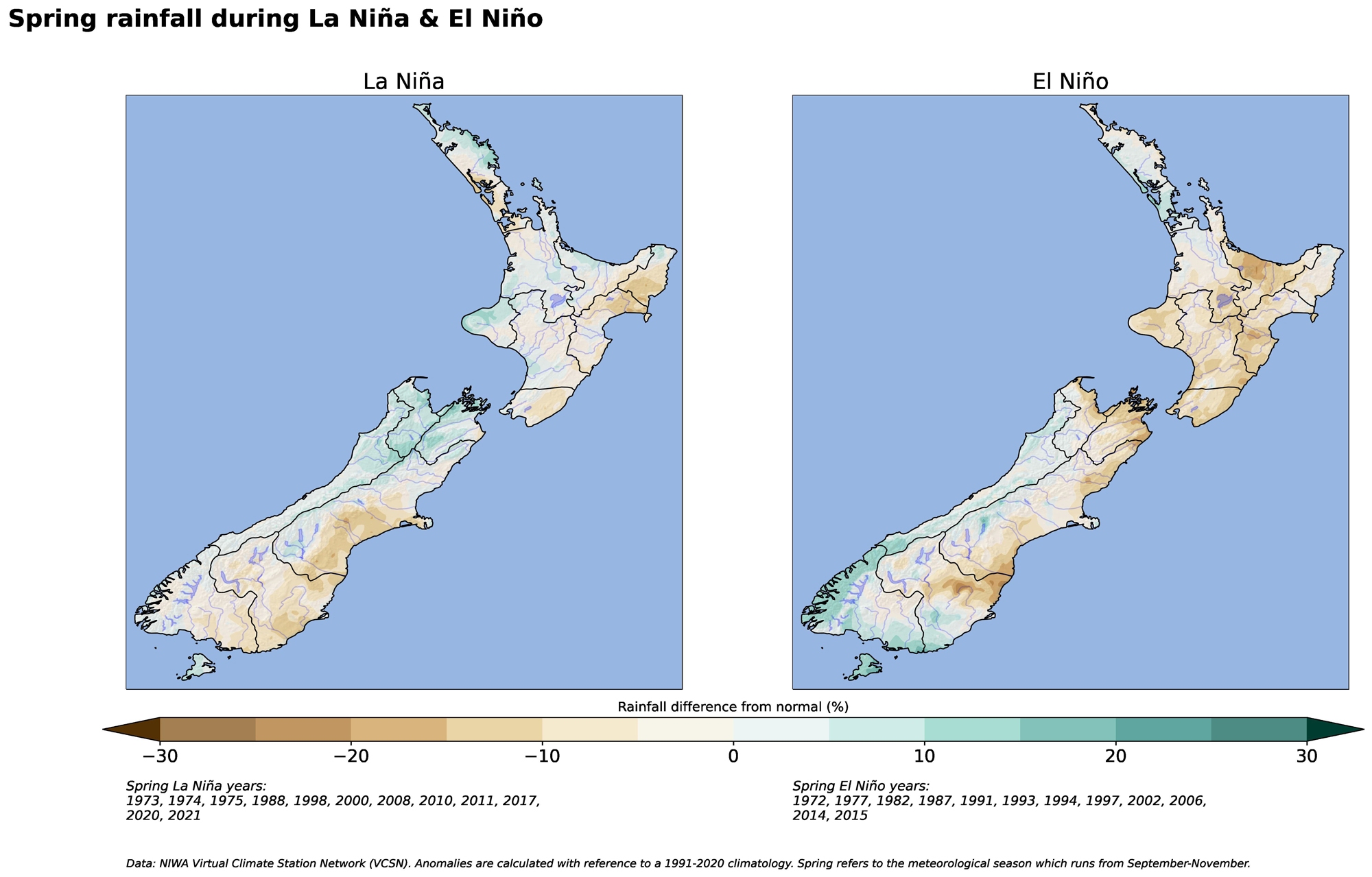

Using the SOI, NIWA has compiled a table of historical El Niño and La Niña events as well as maps that help illustrate the average rainfall patterns during historical events.

| ENSO events | Years |

|---|---|

| Summer – El Niño | 1972-73, 1977-78, 1982-83, 1986-87, 1991-92, 1992-93, 1994-95, 1997-98, 2004-05, 2009-10, 2015-16 |

| Summer – La Niña | 1973-74, 1975-76, 1988-89, 1998-99, 1999-00, 2000-01, 2007-08, 2008-09, 2010-11, 2011-12, 2020-21, 2021-22 |

| Autumn – El Niño | 1983, 1987, 1992, 1993, 1998, 2005, 2016 |

| Autumn – La Niña | 1974, 1975, 1976, 1989, 1999, 2000, 2008, 2011, 2021, 2022 |

| Winter – El Niño | 1972, 1977, 1982, 1987, 1993, 1994, 1997, 2002, 2015 |

| Winter – La Niña | 1973, 1974, 1975, 1978, 1981, 1988, 1989, 1996, 1999, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2021, 2022 |

| Spring – El Niño | 1972, 1977, 1982, 1987, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1997, 2002, 2006, 2014, 2015 |

| Spring – La Niña | 1973, 1974, 1975, 1988, 1998, 2000, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2017, 2020, 2021 |

Useful links:

Further reading:

-

The impact of El Niño and La Niña on New Zealand's climate

El Niño accounts for less than 25 percent of the year-to year variance in seasonal rainfall and temperature at most locations in New Zealand. -

El Niño maps and charts

View a collection of maps showing the impact of past El Niño and La Niña events. -

Seasonal Climate Outlook

Publication seriesAir temperature, rainfall, soil moisture and river flow predictions for the coming season.