A problem with recruitment is usually indicated by the absence, or very low density, of fish where they would normally be present.

Identifying recruitment problems

If climbing species such as eels, banded kokopu, koaro, and redfin bully are absent, there is likely to be a barrier to the upstream migration of the juveniles downstream. Check your site's altitude and distance upriver from the sea to establish whether they fall within the geographic range where these species would be expected to be found. Distance/altitude plots for the main species are available (LINK). If only inanga or smelt are absent and the sites are within the range for these fish, there is probably a minor barrier downstream, affecting smelt/inanga but not the climbing species (note, these fish are naturally rare during winter months).

Is fish size an issue?

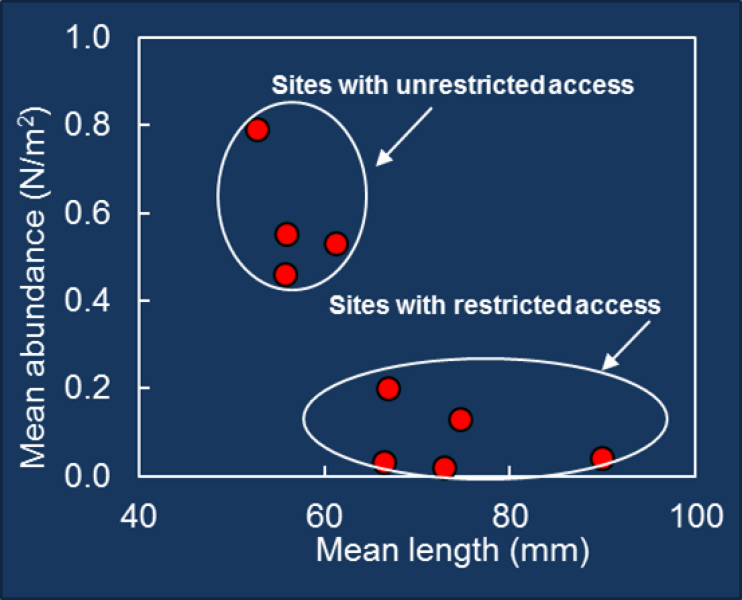

Inspecting size frequency distributions of species can help confirm whether there is a recruitment problem at your stream site. If there are no elvers (<15 cm TL) and only large eels (>40 cm TL) present, elver recruitment is lacking. If a plot of bully abundance versus size indicates a low density of only large bullies, recruitment is limited. In general, no or few juveniles and a low adult density indicate low recruitment.

Are stream barriers restricting fish movement?

A reduction in recruitment can be caused by physical barriers to the upstream movement of juvenile fish from the sea. Barriers include dams, weirs, culverts, tide gates, falls, chutes, sand or gravel bars, or shallow water. However, recruitment may be naturally low for one or even a few seasons due to changes in oceanic conditions that reduce the survival of larval fish.

If there is a physical barrier downstream it may not be the only one, and there may be larger ones elsewhere. Sampling above and below each barrier is required to confirm that it creates a recruitment problem.

If the problem is an artificial barrier such as a dam, weir, or culvert, restoring fish passage may be possible. If the problem is a lack of water depth, increasing channel depth or water flow may be required.

If the problem cannot be fixed by improving fish passage, annual stocking may be required (e.g. relocating eels above dams).

Is stream pollution reducing fish numbers?

Upstream migration can also be prevented by chemical barriers. For example, acidic water from Ruapehu's crater lake prevents native fish from colonising large areas of the Whangaehu River. Pollution can also create chemical barriers in some streams.

Chemical barriers are more difficult to detect but are generally indicated by the scarcity of all diadromous fish species upstream and by the absence of physical barriers. In this case, you need to identify pollutant types present in the stream and research the resource consent history of discharge permits to remove toxic substances from the water: this information should be available from regional councils.

Restocking may be required to re-establish populations of some species.

The upstream migration of banded kokopu is reduced by high levels of turbidity in some rivers (see NIWA's toolset on maximum turbidity levels for freshwater fish).